Five thousand years ago, in a place that is now Iran, ancient hands fed crushed rock into a blazing fire. They watched as ore softened, separated, and slowly revealed something astonishing: copper, glowing like a captured sunrise. That moment marked one of humanity’s earliest steps into metallurgy. The people who lived there transformed raw stone into tools, weapons, and ornaments, sparking a technological revolution whose traces now lie mostly buried or locked away in museums.

Today, the objects themselves are too precious to dissect freely. The techniques those early metallurgists relied on are a puzzle made of fragments, guesses, and rare archaeological finds. But in a new study published in PLOS One, MIT researchers reveal a way to read this ancient story without destroying its evidence. Their method begins not with the prized artifacts, but with something humbler: slag, the dark, hardened waste left behind after smelting.

“Even though slag might not give us the complete picture, it tells stories of how past civilizations were able to refine raw materials from ore and then to metal,” says postdoc Benjamin Sabatini. “It speaks to their technological ability at that time, and it gives us a lot of information. The goal is to understand, from start to finish, how they accomplished making these shiny metal products.”

A New Way to See the Unseeable

Slag may look like a lump of blackened rock, but to the researchers, it is a time capsule. When ore was heated long ago, minerals melted, metals separated, and unwanted components floated to the surface as slag. As this molten waste cooled, it froze droplets, voids, and mineral remnants in place. Each pocket inside it is a record of what those ancient metallurgists did, and how they did it.

The challenge has always been that accessing those records typically requires cutting the slag open, destroying part of it and revealing only one narrow view of its structure. In this new study, Sabatini and senior author Antoine Allanore used a tool borrowed from an entirely different world: CT scanning.

“The Early Bronze Age is one of the earliest reported interactions between mankind and metals,” says Allanore. “Artifacts in that region at that period are extremely important in archaeology, yet the materials themselves are not very well-characterized in terms of our understanding of the underlying materials and chemical processes. The CT scan approach is a transformation of traditional archaeological methods of determining how to make cuts and analyze samples.”

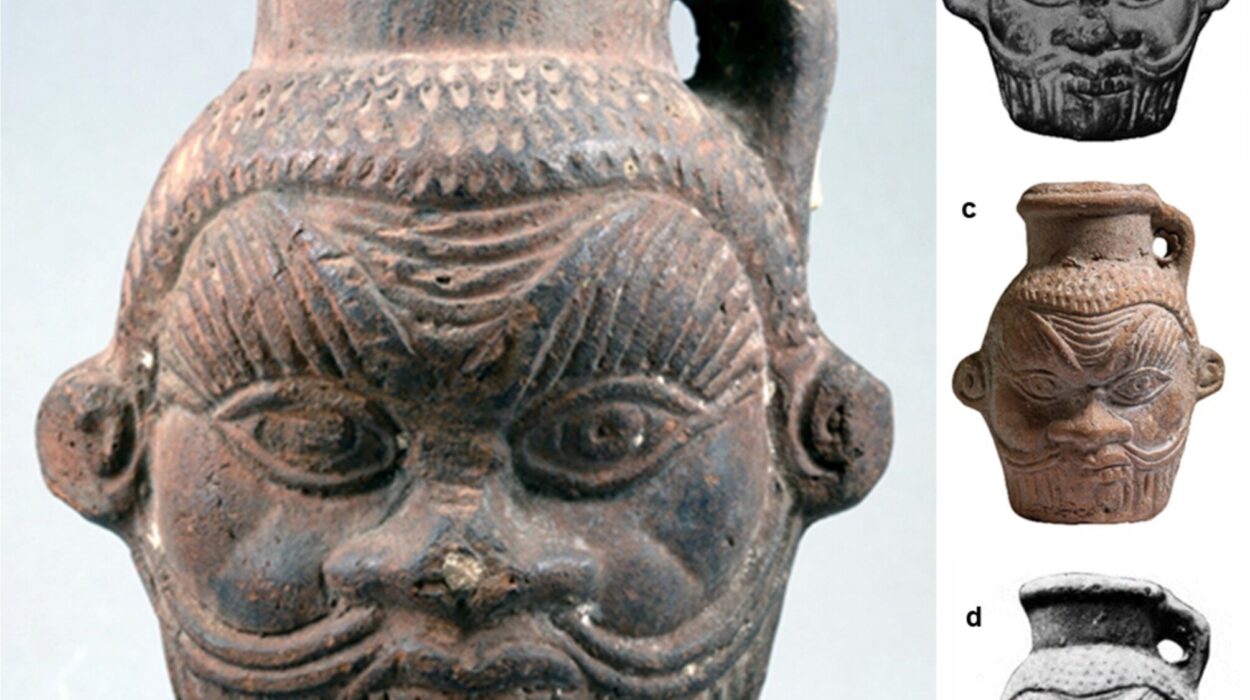

CT scanning, widely known for its medical use, makes it possible to see inside an object without slicing it open. For this study, the researchers scanned slag samples from Tepe Hissar, an ancient settlement dated between 3100 and 2900 BCE. The samples, loaned by the Penn Museum in 2022, come from one of the earliest known sites of copper processing—an organized, trading society where metallurgy may have first flourished.

Slag is notoriously complex. It contains leftovers from ore, unreacted metals, and additives like limestone. Some components, such as arsenic, complicate matters even further. “Slag waste is chemically complex to interpret because in our modern metallurgical practices it contains everything not desired in the final product—in particular, arsenic, which is a key element in the original minerals for copper,” Allanore explains. But arsenic dissolves easily and leaches away, making it unreliable as a long-term clue. “The challenge here is that these minerals, especially arsenic, are very prone to dissolution and leaching, and therefore their environmental stability creates additional problems in terms of interpreting what this object was when it was being made 6,000 years ago.”

The research team needed a noninvasive way to interpret what had survived. They turned to industrial CT scanners, partnering with a local Cambridge startup and using MIT’s own scanner as well. “It was really out of curiosity to see if there was a better way to study these objects,” Sabatini said.

Revealing the Secret Geography Inside Slag

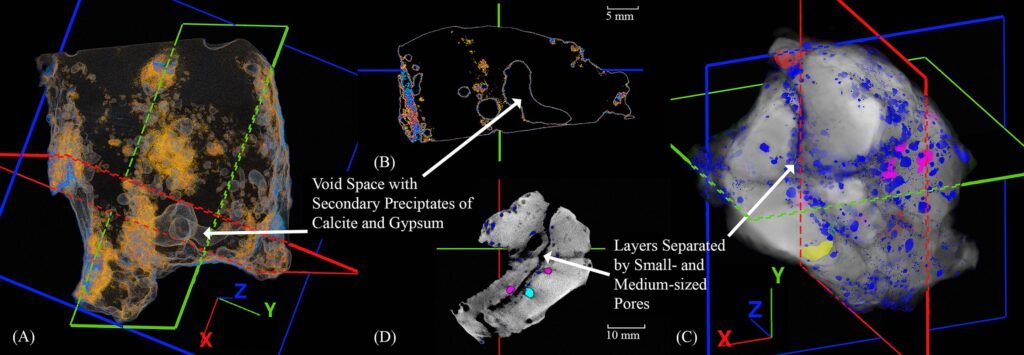

The CT scans produced detailed visual maps of each slag fragment, exposing pores, mineral textures, and most importantly, tiny trapped droplets of metal. These features helped the researchers choose precisely where to section the samples for deeper analysis using more traditional tools such as X-ray fluorescence, X-ray diffraction, and scanning electron microscopy.

Without scanning, choosing a cut is largely guesswork. With scanning, it is guided by knowledge. “My strategy was to zero in on the high-density metal droplets that looked like they were still intact, since those might be most representative of the original process,” Sabatini says. “Then I could destructively analyze the samples with a single slice. The CT scanning shows you exactly what is most interesting, as well as the general layout of things you need to study.”

Some slag pieces from Tepe Hissar had previously shown signs of copper; others contained none at all. The CT images clarified that intact copper-bearing droplets existed in some samples, confirming their connection to copper production. The scans also revealed the winding channels where gases once escaped, leaving behind voids that preserve clues about the temperature, chemistry, and timing of ancient smelting events.

Yet the most contentious element was arsenic. Earlier studies showed metallic arsenide compounds in some slags, raising questions about its movement and purpose. The CT scans revealed that arsenic behaved unpredictably, appearing in different phases and migrating within the slag—or even escaping it entirely. This instability means it cannot be the sole indicator of ancient metallurgical techniques, a realization that may reshape how archaeologists interpret sites like Tepe Hissar.

The Promise of a New Archaeological Tool

The study’s strength comes from its combination of new and old approaches. CT scanning provided the initial map; traditional methods filled in the chemical and structural details. Together, they formed a clearer picture than either could offer alone. The researchers say this hybrid method could transform archaeometallurgy.

“This should be an important lever for more systematic studies of the copper aspect of smelting, and also for continuing to understand the role of arsenic,” Allanore says. “It allows us to be cognizant of the role of corrosion and the long-term stability of the artifacts to continue to learn more. It will be a key support for people who want to investigate these questions.”

Why This Research Matters

The significance of this work reaches far beyond slag. By opening a new window into materials that are usually too delicate or too rare to dissect, CT scanning offers archaeologists a way to reconstruct technologies that shaped the earliest complex societies. It gives researchers the ability to trace how ancient people learned to control fire, transform minerals, and create tools that altered human history. The slag waste once tossed aside by Bronze Age metalsmiths has become a storyteller, and modern science has finally found a way to listen.

Through CT scanning, the researchers have shown that even the most unassuming remains can reveal the skill, creativity, and experimentation of some of the world’s first metallurgists. Understanding how they transformed rock into metal enriches our understanding of human ingenuity itself—and gives archaeology a powerful new tool for uncovering the technologies that built our world.

More information: Benjamin Sabatini et al, A novel application of X-ray computed tomography towards the characterization and interpretation of phase formations, mineral parageneses, and internal features in ancient copper slag from Tepe Hissar, Iran, PLOS One (2025). DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0336603