High above the Earth, carried by a balloon drifting between Sweden and Canada, a telescope named XL-Calibur stared into the darkness. Its target was not a star or a nebula or anything that would catch the casual eye. It was something far smaller, far stranger, and far more violent: a single point of X-ray light marking the presence of the black hole Cygnus X-1, about 7,000 light-years away. From the ground, it would look like nothing more than a flicker. Yet inside that flicker were clues to some of the most powerful and mysterious processes in the universe.

This international team of physicists, including researchers from Washington University in St. Louis, had lifted XL-Calibur into the sky with one ambitious goal: to understand how matter falls into a black hole and how the plunge releases tremendous amounts of light and energy. For them, the balloon was just the beginning. What they really wanted was a closer look at the secret life of a black hole, encoded in the twist and orientation of high-energy light.

Listening to the Universe Through Polarized Light

XL-Calibur doesn’t take ordinary pictures. It listens. Specifically, it listens to the direction in which X-ray light vibrates as it races through space. This vibration, called polarization, acts like a cosmic fingerprint. It carries information about the hot, frenzied material circling the black hole just before disappearing into darkness.

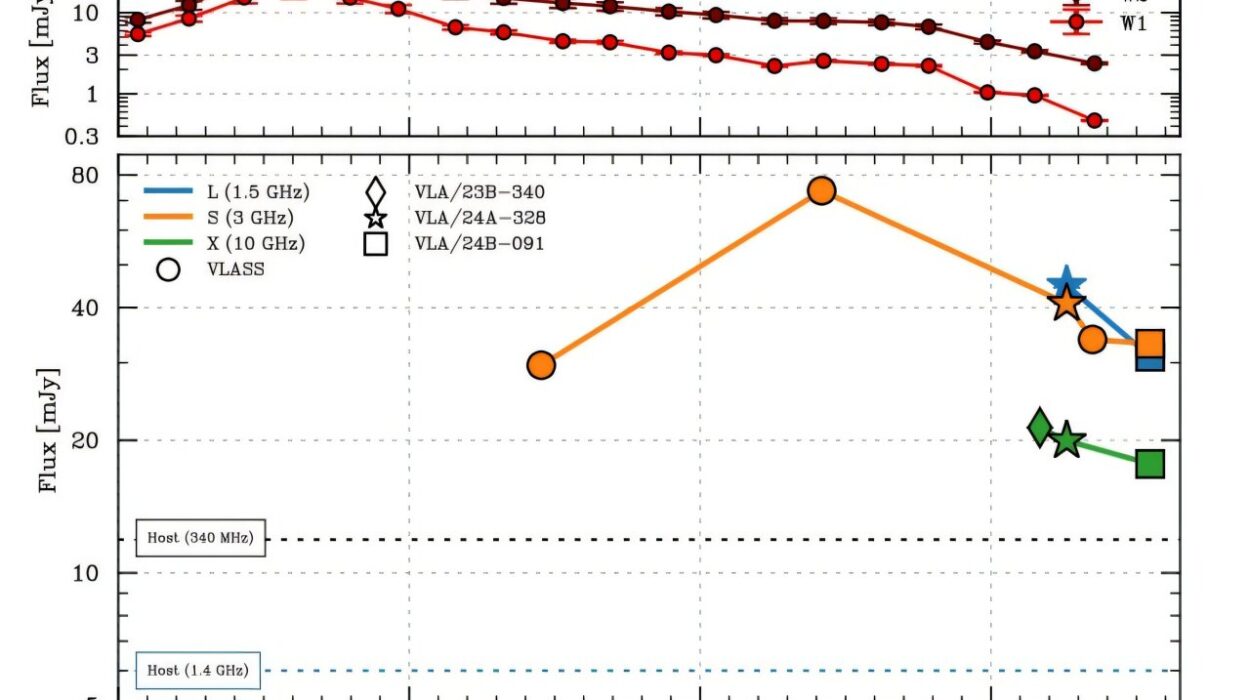

“The observations we made will be used by scientists to test increasingly realistic, state-of-the-art computer simulations of physical processes close to the black hole,” said Henric Krawczynski, the Wilfred R. and Ann Lee Konneker Distinguished Professor in Physics and a fellow at WashU’s McDonnell Center for the Space Sciences. His excitement comes from knowing that this measurement, recently published in The Astrophysical Journal, is the most precise hard X-ray polarization measurement ever made for Cygnus X-1.

To understand why this matters, imagine trying to study a hurricane by examining only a single grain of sand flying inside it. That grain, however tiny, holds clues about the storm’s shape, strength, and motion. The polarized X-rays from Cygnus X-1 are that kind of clue.

Graduate student Ephraim Gau put it simply: “If we try to find Cyg X-1 in the sky, we’d be looking for a really tiny point of X-ray light. Polarization is thus useful for learning about all the stuff happening around the black hole when we can’t take normal pictures from Earth.”

Normal photographs fail because the region around a black hole is far too small, too distant, and too extreme. But polarization carries the imprint of the swirling gas, the magnetic fields, and the violent interactions happening just outside the event horizon. With it, scientists can reconstruct the story.

A Journey from Sweden to Canada and Into the Heart of a Black Hole

The July 2024 XL-Calibur flight was more than a balloon drifting on the wind. It was a laboratory rising above the blur of Earth’s atmosphere, where X-rays become clearer and their polarization measurable. As the balloon rose, carrying the carefully engineered telescope, the team held their breath. This was their chance to observe a black hole in a new way.

The resulting data—from Gau, postdoctoral research associate Kun Hu, and many collaborators—revealed the most detailed picture yet of how X-rays behave near Cygnus X-1. These insights are not just numbers. They are pieces of an unfolding story about gravity, matter, and extreme physics.

Krawczynski sees the bigger picture forming. “Combined with the data from NASA satellites such as IXPE, we may soon have enough information to solve longstanding questions about black hole physics in the next few years,” he said. This collaboration between a balloon telescope and orbiting satellites creates a multi-layered view of cosmic extremes, each instrument filling in a part of the puzzle.

Looking Toward Antarctica and Beyond

Even with this major success, the team is far from finished. XL-Calibur’s journey from Sweden to Canada was just the first act. In 2027, they plan to launch the telescope again—this time from Antarctica, where long-duration balloon flights can capture even more data. They hope not only to revisit Cygnus X-1 but also to study additional black holes and neutron stars.

The promise of Antarctica isn’t just dramatic scenery. The polar winds allow a balloon to circle the continent for weeks, offering more time, more stability, and more observations. For a telescope hunting polarized X-rays, time is everything.

The project itself is woven from expertise around the globe. XL-Calibur is the work of WashU, the University of New Hampshire, Osaka University, Hiroshima University, ISAS/JAXA, the KTH Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm, and NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center and Wallops Flight Facility, along with thirteen additional research institutes. It is a distinctly human endeavor—many minds, many countries, one shared goal.

Why This Discovery Matters

At first glance, measuring the polarization of X-rays from a distant black hole might sound like an obscure detail. But inside that detail lies a fundamental question: how do black holes transform falling matter into light energetic enough to cross galaxies? This process is one of the great engines of the universe, powering jets, shaping galaxies, and influencing the evolution of cosmic structures.

Understanding how matter behaves near a black hole’s edge helps scientists test the laws of physics under the most extreme conditions imaginable. These environments cannot be recreated on Earth. They exist only in the cosmos, and only tools like XL-Calibur can reveal them.

This research matters because it brings us closer to understanding what happens where gravity is overwhelming, where space and time bend, and where energy explodes from darkness. Each polarized photon from Cygnus X-1 carries a whisper from the edge of a black hole. XL-Calibur has begun to translate those whispers into knowledge—knowledge that may soon answer some of the deepest questions in astrophysics.

In studying a point of light, scientists are illuminating a universe of mysteries.

More information: Hisamitsu Awaki et al, XL-Calibur Polarimetry of Cyg X-1 Further Constrains the Origin of Its Hard-state X-Ray Emission, The Astrophysical Journal (2025). DOI: 10.3847/1538-4357/ae0f1d