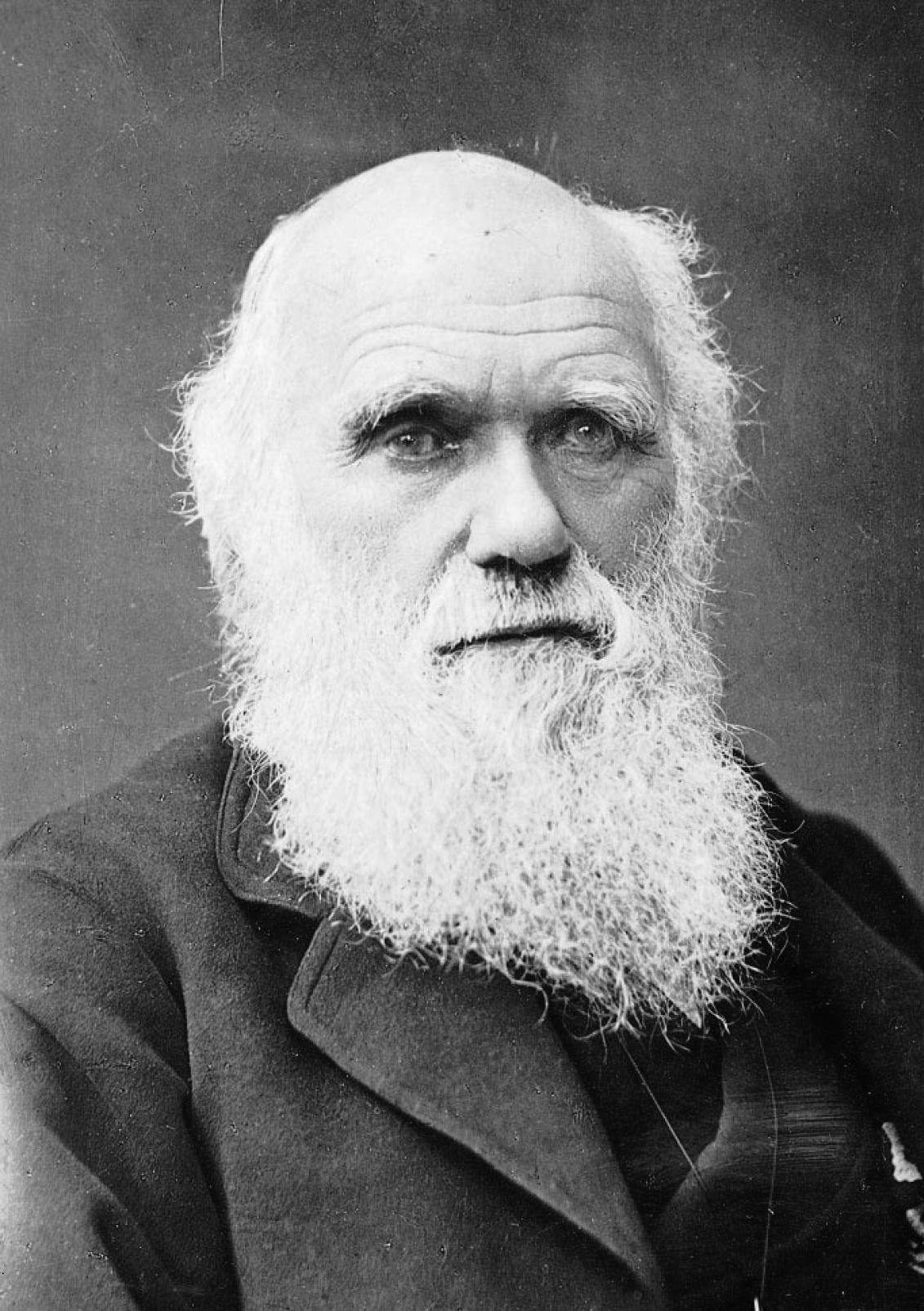

Charles Robert Darwin was born on February 12, 1809, into a world straddling the cusp of modernity and ancient certainty. In the English market town of Shrewsbury, nestled in the rolling hills of Shropshire, Darwin entered life as the fifth of six children in a well-to-do family. His lineage was a tapestry of privilege and intellect. His paternal grandfather, Erasmus Darwin, was a respected physician, poet, and free thinker whose writings flirted with early evolutionary ideas. His maternal grandfather, Josiah Wedgwood, was the famed pottery industrialist whose wealth and progressive ideals shaped a world increasingly concerned with reform.

Charles’s father, Robert Darwin, was a towering figure in both stature and intellect, a man of few words but intense expectations. His mother, Susannah Wedgwood, died when Charles was only eight, leaving behind a memory so faded that he would later admit he could barely recall her face. Raised amid the warm bustle of a large household, Charles’s early life was marked by a deep and insatiable curiosity. He collected rocks, shells, coins, insects—anything that hinted at the natural world’s complexity. While his formal schooling at Shrewsbury School under the stern headmaster Dr. Samuel Butler offered little stimulation, his informal education in the fields, streams, and gardens around his home ignited a love that would grow into a lifelong pursuit.

Even as a child, Darwin was drawn less to doctrine and more to discovery. But for all his natural curiosity, no one—least of all Charles himself—could have predicted the seismic intellectual journey that lay ahead.

Becoming a Naturalist by Accident

At sixteen, Charles began medical studies at the University of Edinburgh, following in the footsteps of his father and grandfather. But the sight of surgery—then practiced without anesthesia—horrified him. He found lectures dull and lectureships uninspiring. Instead, he gravitated toward the company of naturalists, particularly Robert Grant, a marine biologist and a follower of Lamarckian evolutionary thought. Grant’s discussions of transmutation—the idea that species could change over time—stirred something deep within the young student, though Charles remained cautious, even secretive, about such radical views.

When it became clear that medicine would never hold Charles’s heart, his father sent him to Christ’s College, Cambridge, to study for the clergy. A career in the Church was respectable and intellectually unthreatening—a perfect path, it seemed, for a gentleman of means. Yet at Cambridge, Darwin’s love of nature reemerged with renewed vigor. He spent his free time collecting beetles, reading natural theology, and studying under the Reverend John Stevens Henslow, a botanist who would become both mentor and life-changing influence.

It was Henslow who recommended Darwin for a voyage that would shape not only his destiny but the course of science itself. In 1831, at the age of twenty-two, Charles Darwin was invited to serve as the unpaid gentleman naturalist aboard the HMS Beagle. The mission was to chart the coastline of South America and conduct various scientific surveys. Though his father initially objected—fearing the voyage would derail his son’s future—Charles ultimately won his approval with the help of his uncle Josiah Wedgwood II. And so began one of the most consequential voyages in human history.

The Voyage That Changed Everything

The Beagle set sail on December 27, 1831. For nearly five years, Darwin traveled across the Atlantic and Pacific oceans, making landfall in Brazil, Argentina, Chile, the Galápagos Islands, Tahiti, New Zealand, Australia, and South Africa, among other locales. Though his official role was as a companion to Captain Robert FitzRoy, Darwin soon transformed the journey into a vast scientific expedition of his own making.

What Darwin observed was nothing less than a living museum of biodiversity. Fossilized bones of extinct creatures in South America resembled modern armadillos and sloths. Coral reefs revealed intricate patterns of growth and decay. Volcanoes, earthquakes, and shifting coastlines hinted at a dynamic Earth, not a static one. Everywhere he looked, life seemed adapted—uniquely and exquisitely—to its environment.

Nowhere was this more pronounced than in the Galápagos Islands, where finches, mockingbirds, and tortoises varied subtly from one island to the next. Though he did not immediately grasp the implications, Darwin took meticulous notes, collected specimens, and allowed his mind to slowly and cautiously entertain forbidden thoughts. Could species change? Could they, over long periods of time, evolve from common ancestors?

By the time the Beagle returned to England in October 1836, Darwin was no longer just a young gentleman with an interest in nature. He was a man carrying a dangerous idea.

Years in the Shadows of Thought

Back in England, Darwin became a scientific celebrity. His journals were published to popular acclaim, and he began working on the geology and zoology of his findings. But beneath the public recognition lay a private torment. The idea of evolution by natural causes—especially through the process he had begun to envision as “natural selection”—was intellectually electrifying and morally terrifying.

Victorian England was steeped in religious tradition. The idea that species were immutable, created by God in fixed forms, was not just a belief but a cultural foundation. To challenge it was to risk professional exile and personal disgrace. So Darwin worked in secret. He studied pigeons, barnacles, orchids, and earthworms. He read Thomas Malthus, whose writings on population growth helped Darwin realize that, in nature, more individuals are born than can survive, and those with advantageous traits are more likely to reproduce. This, he reasoned, was the engine of change.

For over twenty years, Darwin refined his theory in silence. He amassed overwhelming evidence but resisted publication. He feared the backlash and perhaps feared his own hubris. He was also frequently ill, suffering from chronic nausea, fatigue, and anxiety—ailments that may have been psychosomatic, rooted in the stress of carrying such a revolutionary burden.

The slow march toward publication continued until, in 1858, a letter arrived from Alfred Russel Wallace, a young naturalist working in the Malay Archipelago. Wallace had independently conceived the idea of natural selection and asked Darwin for his opinion. Shocked and heartbroken, Darwin feared he had waited too long. But in an act of integrity rare in science, he arranged for both his and Wallace’s ideas to be presented together at the Linnean Society in London. Darwin’s longer, more detailed exposition, however, soon overshadowed Wallace’s.

The Book That Shook the World

On November 24, 1859, Darwin published On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection. It sold out on the first day. The book was a masterpiece of clarity, caution, and scientific reasoning. Darwin did not speak of human evolution—at least not explicitly—but the implications were unmistakable. Species evolved. Life changed. The Tree of Life was not static but branching, dynamic, ever unfolding.

The reaction was volcanic. Some scientists praised the work as genius; others condemned it as blasphemy. Religious leaders attacked it as atheistic, while theologians like Asa Gray sought to reconcile it with divine providence. The famous caricature of Darwin with an ape’s body soon circulated in satirical newspapers, mocking his theory and portraying him as an enemy of faith and decency.

But Darwin remained calm. He did not seek confrontation. He rarely defended his theory in public. Instead, he continued to write, revise, and support younger scientists who took up his cause. Over time, his ideas gained acceptance—not because of fashion or force, but because they explained so much so well. They unified biology, fossil records, and the geographical distribution of species. They provided a coherent explanation for nature’s diversity that no rival theory could match.

A Family Man and Reluctant Icon

Though Darwin’s name became synonymous with evolution, he never ceased being a private man. He lived in a country home in Downe, Kent, with his beloved wife, Emma Wedgwood—his cousin—whom he had married in 1839. Their marriage was one of deep affection but also philosophical tension. Emma was devoutly religious; Charles, increasingly agnostic. Their correspondence reveals a gentle, mutual respect, though Darwin was painfully aware that his views wounded her faith.

They had ten children, seven of whom survived to adulthood. Darwin was a devoted father, tender and engaged. He often involved his children in his experiments and doted on them with affection. Yet his health remained fragile, and periods of intense work were often followed by debilitating illness.

Despite his discomfort with fame, Darwin became a sage figure in British science. He corresponded with scientists, philosophers, and thinkers around the world. He published several follow-up works, including The Descent of Man, where he finally addressed human evolution directly, and The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals, which linked animal and human behavior through evolutionary continuity.

Darwin never stopped learning, questioning, wondering. In his final years, he turned his attention to the humble earthworm, studying its role in soil fertility with the same passion he had once devoted to the origins of life. Even in small things, he saw vast implications.

Death of the Naturalist, Birth of a Legacy

Charles Darwin died on April 19, 1882, at the age of seventy-three. He had lived long enough to see many of his ideas vindicated and his name celebrated, though controversy still swirled. He had requested a simple burial at his local church in Downe, but such was the magnitude of his impact that he was laid to rest in Westminster Abbey, near Sir Isaac Newton—a symbolic homecoming for a man whose thoughts had changed the nature of science itself.

Darwin’s legacy did not end with his death. It deepened. In the decades that followed, his theory of evolution became the cornerstone of modern biology. Genetics, which was still in its infancy during Darwin’s life, later confirmed and expanded his insights. The synthesis of Darwinian evolution with Mendelian inheritance in the 20th century gave rise to the modern evolutionary synthesis, providing the genetic mechanism that Darwin could only theorize.

His ideas also sparked debates far beyond science. Evolution challenged religious doctrine, inspired artistic movements, influenced philosophy, and even shaped political ideologies—for better and worse. Darwin himself would have abhorred the misuse of his ideas in social Darwinism and eugenics, ideologies that twisted natural selection into brutal justification for inequality.

Yet through it all, the core of Darwin’s vision remained unshaken: life is connected. From the tiniest microbe to the most complex mammal, all living things share a common ancestry, shaped not by design but by the subtle, powerful process of natural selection across immense spans of time.

A Mind Still Evolving

Charles Darwin did not see himself as a revolutionary. He was a quiet thinker, methodical, self-critical, deeply aware of his limitations. He hesitated, revised, doubted, and always asked more questions than he answered. But in that humility lay his strength. Unlike many great figures, Darwin did not try to impose a vision upon the world. He tried to understand the world on its own terms—and in doing so, he transformed how we understand ourselves.

He reminded us that we are not separate from nature, but part of it. That our origins are not in myth, but in history. That life is not static, but dynamic. His work urges us to look at the world with open eyes and an open mind, to marvel at both the grandeur and the simplicity of natural laws.

In a letter to his friend Asa Gray, Darwin once wrote: “It seems to me absurd to doubt that a man may be an ardent theist and an evolutionist.” He was not interested in smashing belief, only in illuminating truth.

The voyage of the Beagle never truly ended. It continues in every field study, in every genome sequenced, in every student who marvels at the fossil record or watches a bird adapt to a changing environment. Darwin’s ideas remain alive because they are not dogma but dialogue—a conversation between nature and the human mind.

And so, Charles Darwin lives on not only in the annals of science but in every question asked with genuine curiosity, every answer tested against evidence, every truth accepted with wonder and humility.