A surprising and potentially game-changing discovery has emerged from recent research presented at the European Congress on Obesity (ECO 2025): individuals taking the popular weight-loss drugs liraglutide or semaglutide slashed their alcohol consumption by nearly two-thirds within just four months. These medications, originally developed to treat type 2 diabetes and later approved for obesity management, are now revealing an unexpected and promising benefit—curbing cravings for alcohol.

This revelation comes at a critical time. Alcohol use disorder (AUD) is a devastating public health crisis, contributing to an estimated 2.6 million deaths annually. That’s approximately 4.7% of all global fatalities. Traditional treatments for AUD, such as cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), motivational enhancement therapies, and medications like nalmefene or disulfiram, have seen only partial and short-lived success. Up to 70% of individuals treated for alcohol dependence relapse within the first year. But the discovery that GLP-1 (glucagon-like peptide-1) analogs might suppress alcohol cravings adds an intriguing new dimension to the ongoing search for more effective and sustainable therapies.

A Real-World Study with Real Impact

This unexpected effect was uncovered by a research team led by Professor Carel le Roux at University College Dublin, in collaboration with colleagues in Saudi Arabia. To investigate the link between GLP-1 analogs and alcohol consumption, the team conducted a prospective real-world study at a Dublin-based obesity clinic.

The study followed 262 adults with a body mass index (BMI) of 27 kg/m² or higher—indicating overweight or obesity—79% of whom were women, with an average age of 46. Participants were prescribed either liraglutide or semaglutide, medications that mimic GLP-1, a naturally occurring hormone involved in appetite regulation and insulin secretion.

Before starting the medications, participants were grouped based on self-reported drinking habits: non-drinkers (12%), rare drinkers (20%), and regular drinkers (68%)—the latter defined as consuming more than 10 units of alcohol per week. One UK unit of alcohol is equivalent to 10 milliliters (or 8 grams) of pure alcohol, roughly the amount found in a small glass of wine or half a pint of average-strength beer.

The Numbers Tell a Powerful Story

After an average follow-up period of just four months, 188 participants had updated alcohol intake data. Remarkably, not a single one reported an increase in their alcohol consumption. Instead, the opposite was true: their average intake had plummeted.

Overall, average alcohol consumption dropped from 11.3 units per week to just 4.3 units—a nearly 62% reduction. Among regular drinkers, who began at a baseline of 23.2 units per week, the average dropped to 7.8 units. That’s a staggering 68% decline.

This level of reduction mirrors the effects of nalmefene, a drug currently licensed in Europe to treat alcohol dependence by reducing the desire to drink. What makes this even more intriguing is that patients taking GLP-1 analogs for weight loss reported that their reduced urge to drink required little to no conscious effort.

The Science Behind the Surprise

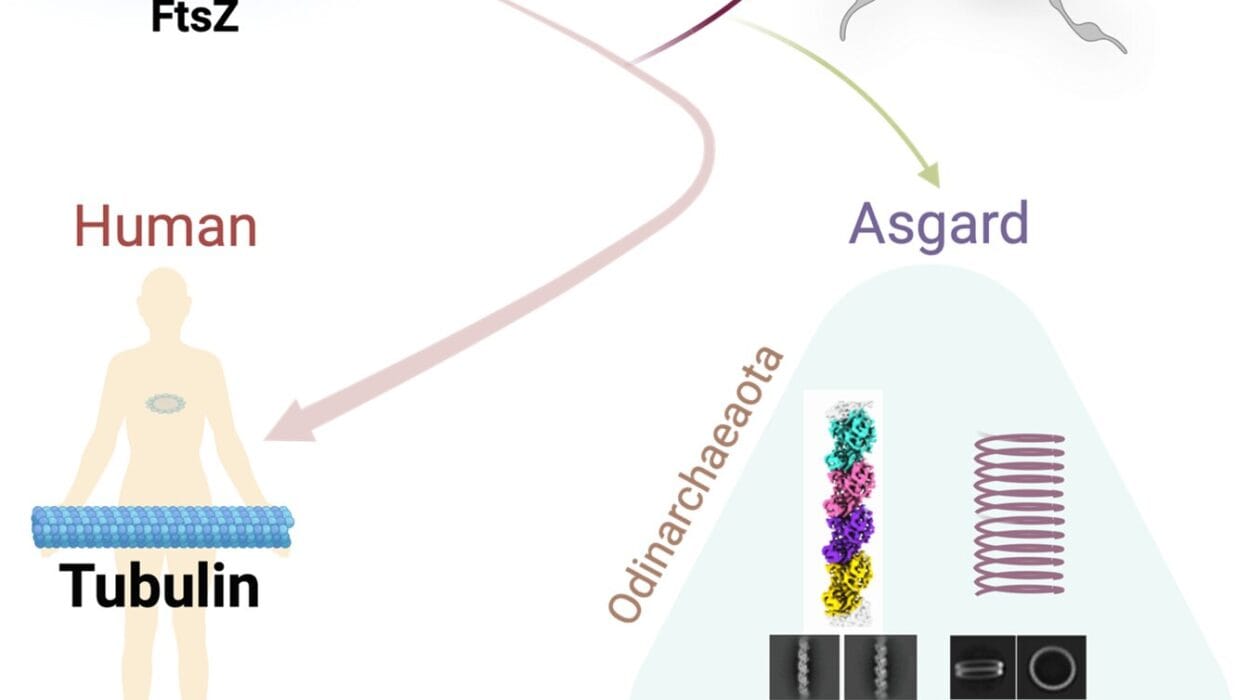

How exactly do these weight-loss drugs suppress alcohol cravings? The mechanism isn’t fully understood, but emerging theories suggest that GLP-1 analogs interact with brain circuits involved in reward, impulse control, and craving—areas that are not entirely under conscious regulation.

GLP-1 receptors are found in subcortical regions of the brain, including the nucleus accumbens and the ventral tegmental area, both of which are known to play a role in addiction and reward-driven behaviors. By stimulating these receptors, GLP-1 analogs may help regulate dopamine signaling—the same neurotransmitter that’s hijacked by addictive substances like alcohol, nicotine, and opioids.

Professor le Roux explains it succinctly: “The exact mechanism of how GLP-1 analogs reduce alcohol intake is still being investigated, but it is thought to involve curbing cravings for alcohol that arise in subcortical areas of the brain that are not under conscious control. Thus, patients report the effects are ‘effortless.’”

This may help explain why those in the study weren’t struggling or fighting urges—they simply didn’t feel the need to drink as much. That kind of subconscious modulation of behavior could be a major breakthrough in the treatment of addiction, a field often marked by high relapse rates and intense internal struggle.

From Mice to Humans: The Long Road to Discovery

GLP-1 analogs had previously shown promise in reducing alcohol intake in animal models. In studies with mice and rats, administration of these drugs led to lower voluntary alcohol consumption, fewer signs of withdrawal, and less compulsive drinking behavior. However, translating results from animal models to humans is never guaranteed.

This real-world human study bridges that gap and provides one of the first robust data sets confirming that the phenomenon also exists in people. While other small-scale clinical observations had hinted at similar effects, the Dublin study represents a critical step forward in documenting these outcomes systematically.

Limitations and Strengths of the Study

Like all studies, this one has its limitations. The sample size, while substantial for a clinical obesity study, remains relatively small in the context of addiction research. The study also lacked a placebo or control group, and alcohol intake was self-reported, which can introduce recall bias or underreporting.

Despite these caveats, the study’s strengths are significant. It was prospective, meaning that alcohol consumption data was collected over time, not just in retrospect. The real-world clinical setting adds to its relevance, as participants were not part of a tightly controlled experimental protocol but were instead receiving treatment in a standard medical environment—mirroring what might happen in everyday practice.

A Future Beyond Obesity Treatment?

GLP-1 analogs have already proven themselves effective in treating obesity, with drugs like liraglutide (Saxenda) and semaglutide (Wegovy, Ozempic) generating dramatic weight loss in patients across multiple studies. But the possibility that these drugs might also treat behavioral addictions like alcohol use disorder could represent a seismic shift in how we approach both obesity and addiction.

Interestingly, many of the underlying psychological and neurochemical pathways of compulsive overeating overlap with those of substance use disorders. Both involve the dysregulation of reward systems and dopamine transmission, both are chronic and relapsing, and both require more than just willpower to overcome.

If GLP-1 analogs prove capable of blunting cravings not only for food but also for alcohol, they may represent a dual-purpose treatment that addresses both obesity and addiction—two of the most pressing public health challenges of our time.

What Comes Next?

This study adds weight to the growing interest in GLP-1 analogs as potential therapies beyond weight loss and diabetes. Randomized controlled trials specifically focused on alcohol use disorder are now urgently needed to confirm and expand on these findings. If replicated at scale, these medications could be added to the relatively short list of pharmacological tools currently available to help individuals reduce or abstain from alcohol.

Moreover, researchers are beginning to explore whether GLP-1 analogs could also be beneficial for other forms of addiction, such as nicotine or opioid dependence. If the mechanisms by which they suppress cravings apply broadly across substances, we could be looking at the dawn of a new era in addiction medicine.

A Silent Revolution

What’s perhaps most striking about this discovery is its subtlety. Unlike traditional treatments for addiction, which often require intensive effort, therapy, or pharmacological suppression with significant side effects, GLP-1 analogs seem to work quietly. People taking these medications don’t experience a painful battle of willpower—they just don’t feel like drinking.

This quiet, “effortless” shift in behavior could make GLP-1 analogs uniquely suited for long-term use. In contrast to treatments that depend on constant mental vigilance, these drugs may be helping patients bypass conscious resistance entirely, modifying behavior at the neurological root.

Conclusion: A Promising Step Toward Integrated Health

The results from Professor le Roux’s study are more than just an academic curiosity—they hint at a revolutionary new approach to treating addiction and obesity simultaneously. With alcohol consumption sharply reduced among regular drinkers who were taking GLP-1 analogs for weight loss, science is inching closer to a unified model of treating complex, overlapping disorders with a common neurobiological foundation.

While more research is necessary to determine the long-term effects and establish clear clinical guidelines, one thing is certain: the horizon of addiction treatment is expanding. And at that horizon stands a class of medications that, until now, had been known mostly for trimming waistlines. Today, they might also help lighten the burden of addiction.

Reference: Maurice O’Farrell et al, Glucagon‐like peptide‐1 analogues reduce alcohol intake, Diabetes, Obesity and Metabolism (2025). DOI: 10.1111/dom.16152