The human body is a marvel of biological engineering, a complex network of systems working in tandem to maintain life, support function, and enable continuation. Among these, the reproductive system holds a unique place—not merely as a biological necessity, but as a profound aspect of identity, social interaction, and human culture.

In scientific terms, the reproductive system is the set of organs and processes responsible for producing offspring. But its role extends far beyond reproduction. It affects hormonal balance, bone density, emotional health, physical appearance, and even cognitive function.

In this expansive exploration, we’ll delve deep into the male and female reproductive systems—not just in terms of anatomy, but through the lens of modern medical science. We’ll look at development, hormones, health challenges, fertility, disease, and cutting-edge research. This is a journey through biology and beyond, into the evolving science of human life.

Foundations of Difference: How Reproductive Systems Develop

To understand the differences between male and female reproductive systems, we must start at the beginning: the embryo.

At conception, a fertilized egg receives 23 chromosomes from each parent. One pair of these chromosomes—XX for females or XY for males—determines sex. Interestingly, in the earliest weeks of development, all embryos have the same foundational reproductive structures. These are known as the bipotential gonads, capable of developing into either testes or ovaries.

By the sixth or seventh week, if the embryo has a Y chromosome, a gene called SRY (Sex-determining Region Y) activates. This triggers the formation of testes, which in turn begin producing testosterone and Müllerian Inhibiting Substance (MIS). Testosterone supports the development of male internal and external genitalia, while MIS causes the regression of female reproductive structures.

In the absence of SRY (as in XX embryos), the gonads develop into ovaries. Female reproductive structures such as the uterus, fallopian tubes, and upper vagina form from the Müllerian ducts.

Though the pathways diverge, the origins are shared. This biological symmetry is one reason why some structures in males and females are homologous—formed from the same embryonic tissues, despite having different functions.

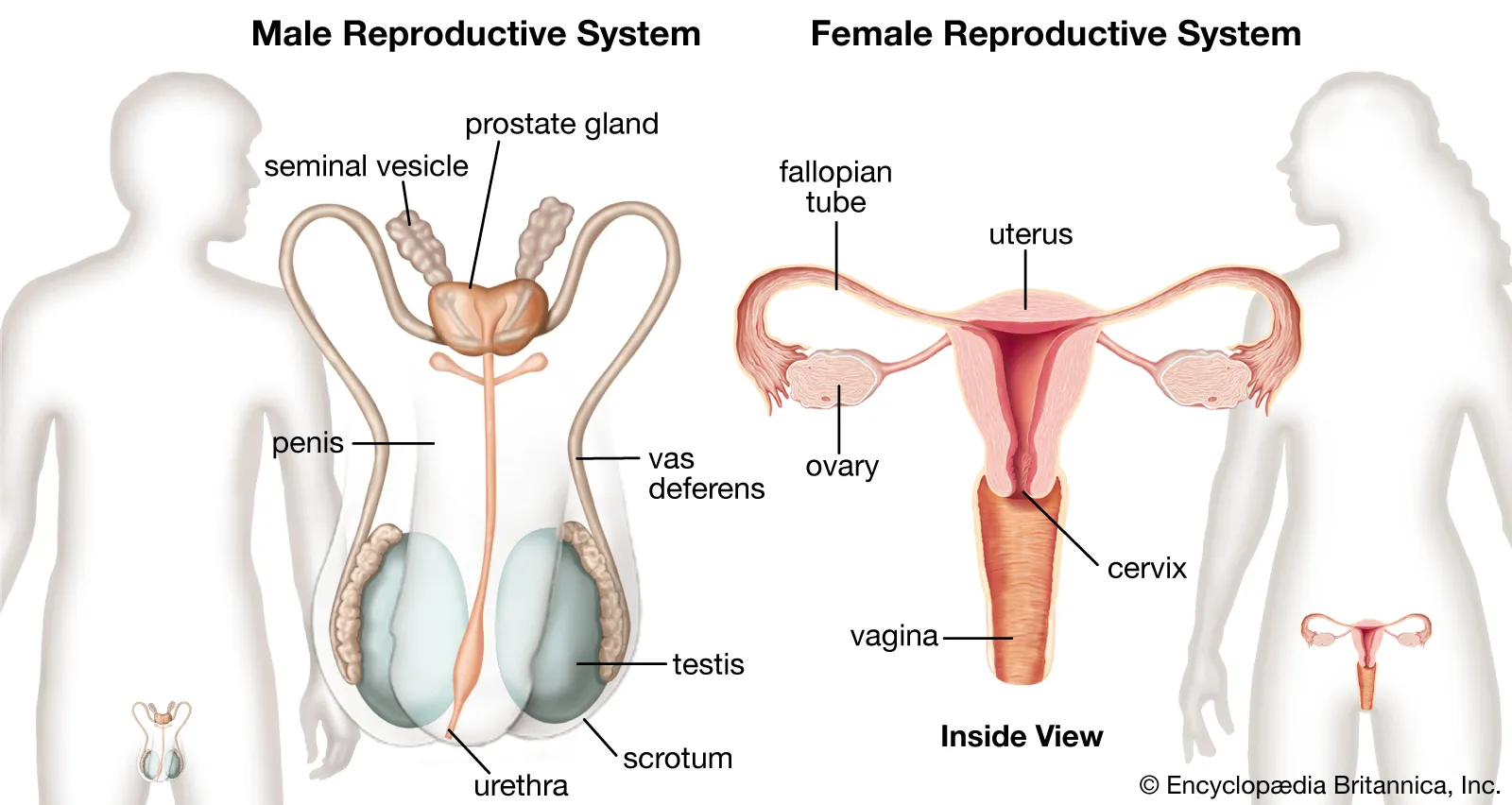

Male Reproductive System: Anatomy and Function

The male reproductive system is primarily designed to produce, mature, and deliver sperm—the male gametes that carry half the genetic material necessary for reproduction.

Key Organs and Structures

- Testes: The two testicles are where sperm and testosterone are produced. Each testis contains seminiferous tubules—tight coils where spermatogenesis occurs.

- Epididymis: Located on the back of each testicle, this is where sperm mature and are stored.

- Vas deferens: A long duct that transports mature sperm during ejaculation.

- Seminal vesicles: Glands that produce seminal fluid, which nourishes sperm and facilitates their movement.

- Prostate gland: Adds fluid to semen, including enzymes and proteins vital for sperm function.

- Penis and urethra: The external organ responsible for delivering semen and also involved in urinary excretion.

Sperm Production: A Continuous Cycle

Unlike egg production in females, sperm production is continuous throughout adult male life. Spermatogenesis takes about 64–74 days from start to finish. Once formed, sperm are stored in the epididymis until ejaculation.

Sperm are extremely small cells, consisting of a head (which carries genetic material), a midpiece (packed with mitochondria for energy), and a tail (used for movement).

A healthy male produces millions of sperm each day, though only one sperm is needed to fertilize an egg.

Female Reproductive System: A Cyclical Symphony

The female reproductive system is cyclical and multifunctional. Not only does it produce gametes (eggs), but it also supports conception, gestation, and childbirth.

Key Organs and Structures

- Ovaries: These small, almond-shaped glands produce eggs (ova) and secrete hormones like estrogen and progesterone.

- Fallopian tubes: These narrow tubes carry eggs from the ovaries to the uterus. Fertilization usually occurs here.

- Uterus: A muscular organ where a fertilized egg implants and develops into a fetus.

- Endometrium: The inner lining of the uterus that thickens in preparation for a possible pregnancy and sheds during menstruation.

- Cervix and vagina: The cervix connects the uterus to the vagina, which serves as the birth canal and the organ for sexual intercourse.

Ovulation: A Monthly Miracle

At birth, females have about one to two million immature eggs. By puberty, this number drops to around 300,000. During each menstrual cycle, a cohort of follicles (each containing one egg) begins to mature, but usually only one becomes dominant and is released during ovulation.

Ovulation is typically followed by the luteal phase, during which the body prepares for pregnancy. If fertilization does not occur, hormone levels drop, the endometrium is shed, and menstruation begins.

Unlike sperm, egg production is finite. A woman’s supply of eggs gradually declines with age, leading to menopause—the end of reproductive capacity, typically occurring between 45 and 55.

Hormonal Control: The Invisible Orchestra

Both male and female reproductive systems are controlled by hormones—chemical messengers secreted by endocrine glands that regulate processes like development, sexual function, and fertility.

The Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal Axis

This regulatory network is common to both sexes and begins in the hypothalamus, which secretes gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH). GnRH prompts the pituitary gland to release:

- Luteinizing hormone (LH)

- Follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH)

In males, LH stimulates Leydig cells in the testes to produce testosterone. FSH supports spermatogenesis in the seminiferous tubules.

In females, FSH stimulates follicle growth in the ovaries. LH triggers ovulation and supports the corpus luteum, which secretes progesterone.

Testosterone vs. Estrogen and Progesterone

- Testosterone is the primary male sex hormone. It drives the development of male genitalia, secondary sex characteristics (facial hair, muscle growth, voice deepening), and sperm production.

- Estrogen governs female secondary sex characteristics (breast development, fat distribution) and supports endometrial growth.

- Progesterone prepares the uterus for pregnancy and maintains early gestation.

Together, these hormones orchestrate the sexual and reproductive functions of the human body with precise timing and feedback loops.

Medical Insights into Male Reproductive Health

Common Disorders

- Erectile Dysfunction (ED): Difficulty achieving or maintaining an erection, often related to vascular, neurological, or psychological causes.

- Infertility: Affects about 7% of men. Causes include low sperm count, poor motility, hormone imbalances, or genetic defects.

- Varicocele: Enlarged veins in the scrotum that can affect sperm quality.

- Testicular cancer: Most common in younger men (ages 15–35), but highly treatable if caught early.

- Prostatitis and Prostate Cancer: Inflammation or malignancy of the prostate gland, more common with age.

Treatments and Innovations

Modern medicine has revolutionized male reproductive care. Hormone therapy, assisted reproductive technologies (like ICSI—Intracytoplasmic Sperm Injection), and robotic surgery have improved outcomes for countless men.

Research is also underway into male contraceptives, aiming to provide temporary, reversible options beyond condoms or vasectomy.

Medical Insights into Female Reproductive Health

Common Disorders

- Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS): A hormonal disorder causing irregular periods, ovarian cysts, and infertility.

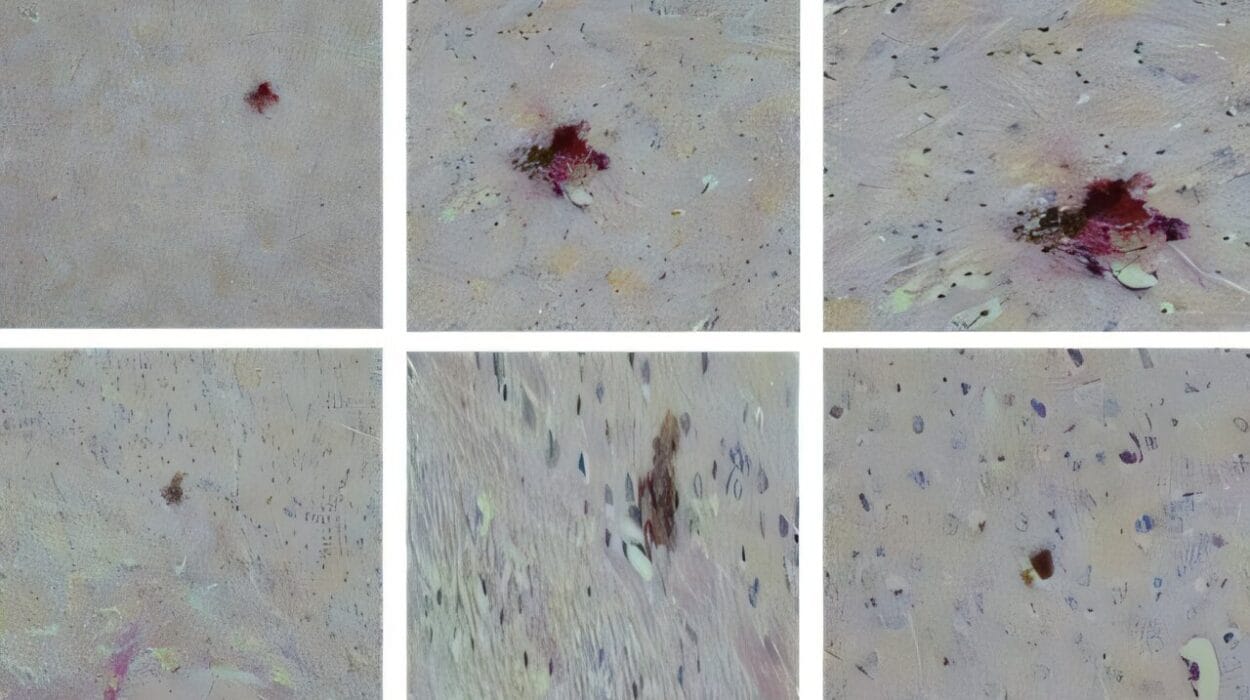

- Endometriosis: Tissue similar to the endometrium grows outside the uterus, causing pain and potential fertility issues.

- Fibroids: Non-cancerous uterine growths that may cause heavy bleeding or pain.

- Cervical and Ovarian Cancer: Serious but often treatable diseases if detected early.

- Infertility: Affects millions of women due to hormonal, anatomical, or age-related factors.

Innovations and Interventions

Advancements in in vitro fertilization (IVF), egg freezing, and hormonal therapies have empowered women with more control over reproduction. Minimally invasive surgeries, hormone balancing, and personalized medicine continue to transform reproductive care.

Vaccines like the HPV vaccine now help prevent cervical cancer, and gene editing holds potential for treating inherited reproductive disorders in the future.

The Role of Age and Reproductive Lifespan

Age impacts male and female reproductive systems differently.

In men, testosterone levels slowly decline after age 30—a process sometimes called andropause. While sperm count and quality decrease, many men remain fertile into advanced age.

Women, on the other hand, experience a more defined reproductive limit. Menopause marks the cessation of menstruation and fertility, typically between 45 and 55. Symptoms include hot flashes, mood changes, and increased risk of osteoporosis and cardiovascular disease due to declining estrogen.

Medical support during menopause has improved dramatically, with hormone replacement therapy (HRT) and lifestyle changes offering relief and protection.

Cultural and Psychological Dimensions

While the reproductive systems are biological, they are deeply entwined with cultural identity, gender roles, and mental health.

Men may face social stigma around infertility or erectile dysfunction. Women often bear disproportionate emotional weight in matters of fertility, pregnancy loss, or birth control.

Medical professionals increasingly recognize the importance of mental health support, inclusive language, and personalized care in reproductive medicine. Transgender individuals, for example, require thoughtful approaches that affirm identity while addressing biological health needs.

Gender, Genetics, and Intersex Variations

Biology doesn’t always fit neatly into binary boxes. Intersex individuals are born with reproductive or sexual anatomy that doesn’t conform to typical definitions of male or female. This may include chromosomal variations (like Klinefelter Syndrome or Turner Syndrome), hormone sensitivity disorders, or ambiguous genitalia.

Medical science is evolving toward non-interventionist, respectful care for intersex people, emphasizing informed consent and bodily autonomy.

Meanwhile, genetic testing is offering new ways to understand individual reproductive potential and risks—bringing both empowerment and ethical questions.

Fertility, Technology, and the Future

The landscape of reproduction is shifting with technology. Assisted reproductive techniques are enabling parenthood for couples facing infertility, single individuals, and LGBTQ+ families.

Emerging research includes:

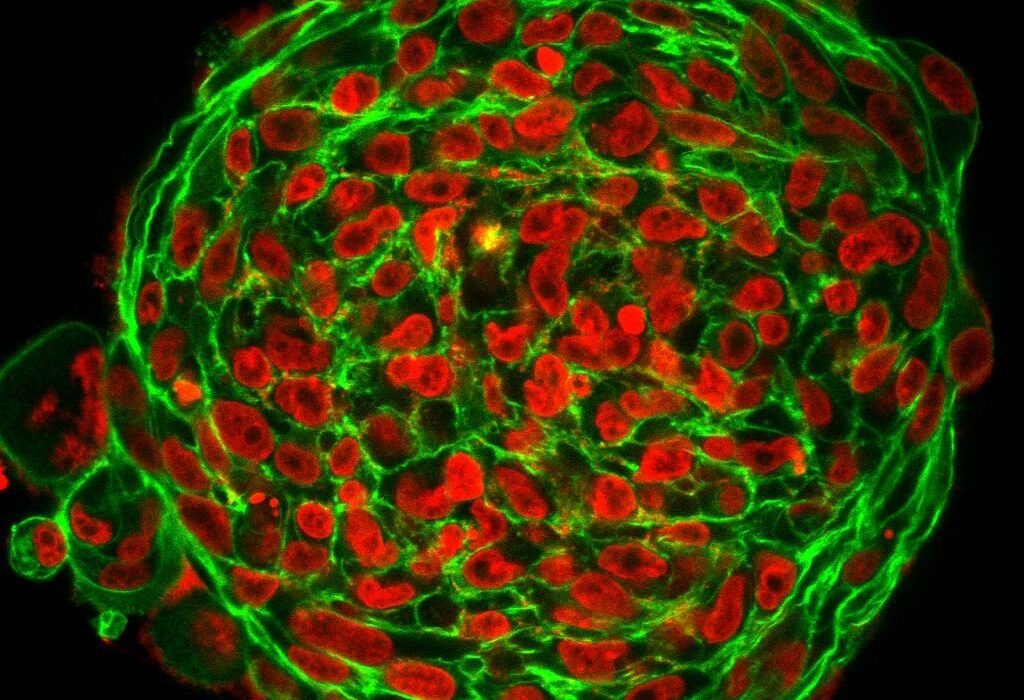

- Artificial gametes from stem cells

- Uterine transplants

- Gene editing to eliminate hereditary diseases

- Non-hormonal male contraceptives

- Artificial wombs that could support preterm infants

Such advances promise to redefine reproduction, parenthood, and even gender roles in the coming decades.

Conclusion: A Shared Human Story

While the male and female reproductive systems differ in anatomy, function, and timing, they share a common purpose: the continuation of life. Each system is a result of millions of years of evolution, finely tuned yet vulnerable to disruption.

Medical science continues to reveal new insights, offering hope for individuals struggling with infertility, disease, or gender dysphoria. It also opens new ethical frontiers, demanding compassion, consent, and cultural awareness.

Understanding these systems is not merely a study in anatomy. It is an exploration of what it means to be human—our origins, our identities, and our shared destiny.

As science moves forward, so must our conversation—expanding beyond binary thinking, embracing diversity, and celebrating the complexity of life itself.