Far to the south, at the bottom of the globe, lies a world of staggering desolation and icy grandeur. Antarctica is the coldest, driest, and windiest continent on Earth. Temperatures in the interior can plunge below -80°C in winter, and even along the coasts, where the climate is slightly more forgiving, they rarely rise above freezing. For much of the year, the sun is either absent or unyieldingly present, casting the continent in long months of darkness or perpetual daylight. Amid this frozen wilderness, life might seem improbable—yet the Antarctic hosts a rich tapestry of uniquely adapted animals that thrive in conditions that would kill most other organisms.

Antarctica is more than just a barren sheet of ice. It is a complex ecosystem shaped by extremes, defined by scarcity, and carved by wind and time. It is a world ruled not by abundance but by constraint, where every adaptation counts and survival hinges on the capacity to endure, to conserve, and to exploit fleeting opportunities. The animals that call this land and sea home are not just surviving—they are masterfully adapted to one of the most inhospitable places on Earth.

Life on the Edge: The Southern Ocean as a Lifeline

Though the Antarctic continent itself is a formidable and mostly lifeless mass of ice, the surrounding Southern Ocean teems with life. This cold, nutrient-rich body of water is the biological engine of the region. Here, microscopic phytoplankton bloom in the brief austral summer, feeding krill—tiny crustaceans that are foundational to the Antarctic food web. In turn, krill nourish a wide variety of animals: fish, squid, penguins, seals, and whales.

Unlike tropical ecosystems, where biodiversity often involves an enormous variety of species, the Antarctic has relatively few—but each is specialized and often exists in enormous numbers. The ecosystem is tightly interlinked. Remove one piece, and the entire system can begin to unravel. This reliance makes Antarctic species both remarkably efficient and vulnerably interconnected.

The Southern Ocean’s upwelling currents, driven by cold winds and the Earth’s rotation, bring nutrient-laden waters to the surface, supporting the growth of phytoplankton and sustaining massive krill swarms. The abundance of krill—estimated in the hundreds of millions of tons—forms the literal bedrock of life here. Everything that swims, dives, or flies in the Antarctic depends on this tiny crustacean, and much of the continent’s animal survival strategy revolves around capitalizing on its boom-and-bust availability.

Emperor of the Ice: The Survival Secrets of the Emperor Penguin

Among the most iconic of all Antarctic creatures, the emperor penguin (Aptenodytes forsteri) is the only animal that breeds during the heart of the Antarctic winter. When temperatures drop below -50°C and winds scream across the sea ice at over 100 km/h, these flightless birds stand in huddled colonies, balancing their eggs on their feet and covering them with a flap of insulating skin.

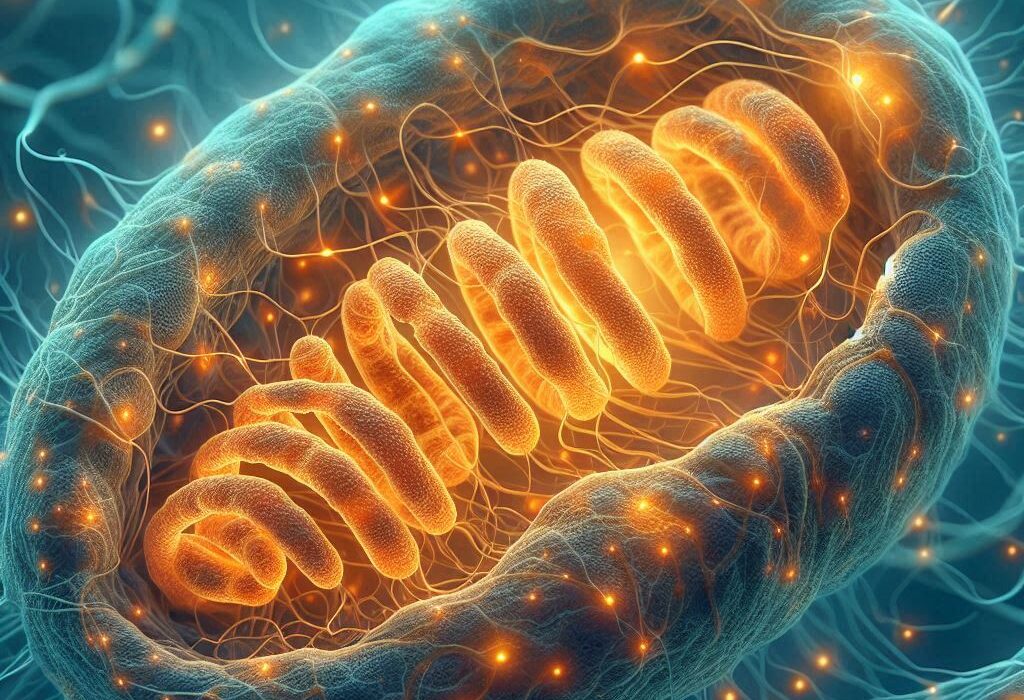

The emperor penguin’s survival strategy is a marvel of thermoregulation, behavioral cooperation, and physiological resilience. Males incubate the eggs for about two months without feeding, losing nearly half their body weight. They survive by relying on thick layers of blubber and a dense coat of waterproof feathers. Their bodies are designed to conserve every ounce of heat: arteries and veins in their legs exchange warmth to minimize heat loss, and they can reduce metabolic rates to endure starvation.

To withstand the bitter cold, emperor penguins form tightly packed huddles, shifting positions in a coordinated dance that ensures each bird spends time in the warmer center and the colder periphery. It is a breathtaking example of cooperative behavior in the animal kingdom, a silent choreography of survival in a world without mercy.

When summer comes and the chicks hatch, the frozen silence gives way to the cries of new life. With the return of the mothers, who have fattened themselves at sea, feeding resumes. In a synchronized effort, parents alternate trips to the ocean and back, ensuring their offspring survive until they’re strong enough to make the journey themselves.

Under the Ice: Seals That Breathe Through Holes in the Sea

Antarctica is home to several species of seals, but none are more uniquely adapted to the environment than the Weddell seal (Leptonychotes weddellii). These rotund, whiskered mammals live most of their lives under the sea ice, surfacing to breathe through holes that they maintain with their teeth. During the long, dark winter, Weddell seals gnaw at the ice edges to keep breathing holes open, an act of perseverance essential to their survival.

Weddell seals are expert divers. They can plunge over 600 meters deep and hold their breath for more than an hour. Their blood carries extraordinary amounts of oxygen, and their muscles are rich in myoglobin, allowing them to operate with minimal oxygen at great depths. When diving, they slow their heart rates dramatically and shunt blood away from non-essential organs to conserve oxygen.

Unlike most mammals, these seals remain in Antarctic waters year-round, giving birth on the sea ice and raising their pups in the frozen silence. Their thick blubber provides insulation, while their metabolic adaptations allow them to thrive in frigid water temperatures that would instantly freeze an unprotected human.

The strategy of remaining near breathing holes, close to the edge of the ice, helps Weddell seals avoid the more aggressive leopard seals (Hydrurga leptonyx), their main predator. It’s a life of constant vigilance, acute spatial memory, and deep physiological adjustment—a life spent not just surviving in the Antarctic but mastering its unique challenges.

The Ultimate Predator: Leopard Seals and Their Reign of Fear

Graceful and deadly, the leopard seal is the apex predator of the Antarctic pack ice. With its elongated, reptilian head, powerful jaws, and sleek body, it is as beautiful as it is formidable. Unlike most seals, which feed primarily on fish and krill, the leopard seal is a voracious carnivore that preys on penguins, other seals, and even large cephalopods.

Leopard seals use stealth and ambush tactics, often lurking beneath ice shelves or near penguin colonies. They strike with terrifying speed, using their powerful bite to kill and tear apart prey. Their teeth are specially adapted to filter krill as well as shear flesh, allowing them to exploit a wide range of food sources depending on availability.

Though solitary, leopard seals play a key ecological role by regulating populations of other animals, including penguins. Their dominance is a testament to the complex food web that exists beneath Antarctica’s icy surface—a system of predator and prey that has evolved over millennia to balance survival with scarcity.

Yet even these fearsome hunters are not invincible. Like all Antarctic animals, leopard seals depend on the integrity of sea ice, which is rapidly changing due to climate warming. Their ability to adapt to diminishing habitats will determine whether they can continue to thrive in this changing world.

Ocean Giants: Whales in the Frozen Deep

Antarctica’s oceanic ecosystems support some of the largest animals on Earth—baleen whales that migrate thousands of kilometers to feed on krill in the Southern Ocean’s nutrient-rich waters. Blue whales, fin whales, humpbacks, and minke whales are among the cetaceans that visit these icy waters each summer to take advantage of the krill blooms.

These whales have enormous appetites, with blue whales consuming up to 4 tons of krill a day. Their feeding strategy is remarkably efficient: they take in massive gulps of water, filter it through baleen plates, and trap the tiny crustaceans en masse. It is a strategy that maximizes energy intake during the brief Antarctic summer, when daylight and productivity peak.

To survive, these whales rely on blubber for insulation and energy storage. During their long migrations to breeding grounds in warmer waters, they do not feed, relying entirely on the fat reserves built up during their Antarctic stay. This feast-and-famine cycle is finely tuned to seasonal productivity, and disruptions in krill availability—whether from climate change or overfishing—could jeopardize this critical balance.

Despite their size and strength, Antarctic whales were nearly hunted to extinction during the 20th century. Today, many populations are recovering under international protection, but they remain vulnerable to environmental change and human interference. Their survival, like that of all Antarctic life, depends on the preservation of their habitat and the food webs that sustain them.

Flightless Navigators: The Resilient World of Penguins

No discussion of Antarctic animal survival would be complete without the inclusion of penguins. These flightless birds are superbly adapted to life in cold, aquatic environments. Several species call the Antarctic home, including the emperor, Adélie, chinstrap, and gentoo penguins. Each has carved out a niche in the harsh ecosystem, using a combination of behavioral and physiological strategies to survive.

Adélie penguins (Pygoscelis adeliae), for example, nest in vast colonies along the rocky Antarctic coast. Their breeding season is tightly synchronized with the seasonal melting of sea ice, ensuring access to open water for feeding. Adélies are agile swimmers and can dive hundreds of times a day to capture krill and fish, using their flippers like wings to “fly” underwater.

Penguins face an array of challenges—from extreme cold and food scarcity to predation by leopard seals and skuas (birds that prey on eggs and chicks). To combat these pressures, penguins rely on social behaviors: nesting in dense colonies, sharing warmth, and coordinating parental care. Their dense plumage and a layer of insulating fat keep them warm in freezing waters.

Climate change presents a serious threat to penguins, especially those dependent on sea ice. Declining ice cover can disrupt breeding and feeding cycles, forcing some colonies to abandon historic nesting sites. Yet penguins have proven surprisingly adaptable, shifting their ranges and altering behaviors in response to environmental pressures. Their future will depend on the pace of change and the global commitment to conserving their ecosystems.

Microscopic Marvels: Invertebrates and Extremophiles

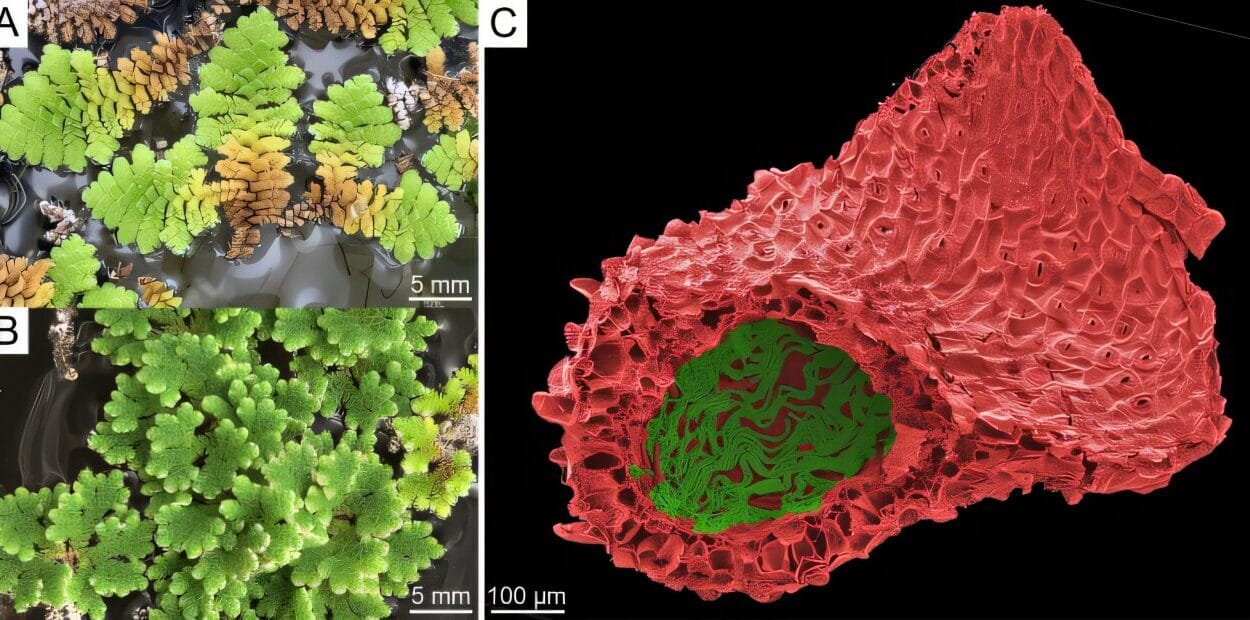

While charismatic megafauna capture most of the attention, some of the most extraordinary Antarctic survivors are microscopic or invertebrate organisms. Beneath rocks, within ice sheets, and under the ocean floor, extremophiles—organisms that thrive in extreme environments—exist in forms that defy conventional biology.

Antarctic krill (Euphausia superba), despite their small size, are arguably the most important animal in the region’s food web. Their ability to survive under sea ice, feed on microscopic algae, and reproduce prolifically makes them the primary food source for nearly all larger animals in the Southern Ocean.

Equally remarkable are the invertebrates that live in the McMurdo Dry Valleys—one of the driest and coldest deserts on Earth. Here, nematodes, tardigrades (water bears), and rotifers survive in subzero soils by entering cryptobiosis, a state of suspended animation in which metabolic processes nearly cease. These creatures can survive desiccation, freezing, and radiation—traits that push the boundaries of what life can endure.

Even in the ice itself, life persists. Microbes have been found in subglacial lakes buried beneath kilometers of ice, existing without sunlight, using chemosynthesis to convert minerals into energy. These life forms provide insight not only into Earth’s resilience but also into the possibility of life on other icy worlds, such as Jupiter’s moon Europa.

The Winds of Change: Threats and Adaptation

Despite the staggering adaptations that allow animals to survive in Antarctica, the region is undergoing rapid transformation. Climate change, driven by rising greenhouse gas emissions, is warming parts of the Antarctic Peninsula at an alarming rate. Sea ice is declining, glaciers are retreating, and ocean temperatures are rising—all with profound implications for Antarctic ecosystems.

Krill populations are particularly sensitive to changes in sea ice, as ice provides both habitat and a platform for algae growth—the krill’s primary food source. A decline in krill threatens not just one species but the entire food web, from penguins to whales.

Moreover, the introduction of invasive species, increased human activity, and the threat of overfishing pose additional challenges. As humans expand their footprint through tourism, research stations, and marine exploitation, the balance of the Antarctic ecosystem becomes increasingly precarious.

Yet there is hope. International agreements like the Antarctic Treaty System and the Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR) have established protected areas and regulated fishing practices. Scientific collaboration continues to monitor ecosystem health, and global awareness is growing. The future of Antarctica may depend on our ability to balance exploration with preservation.

Conclusion: The Triumph of Life in Ice

The animals of Antarctica are not just survivors—they are testaments to the ingenuity of evolution and the tenacity of life. From the stoic emperor penguin to the agile leopard seal, from the colossal blue whale to the microscopic tardigrade, each organism represents a unique solution to the challenges posed by one of Earth’s harshest environments.

Their stories are not only scientifically fascinating but emotionally resonant. They remind us of what life is capable of, how fragile ecosystems can be, and how interconnected our planet truly is. In the face of changing climates and human expansion, the survival of these remarkable creatures depends not only on their adaptations but on our choices.

In preserving the icy realms of the south, we do more than protect a distant wilderness—we honor the resilience of life itself. Antarctica, in all its stark beauty and unforgiving cold, remains a mirror of what is possible when nature is pushed to its limits. And in that mirror, we find not only frozen landscapes and silent snowscapes, but the beating heart of a world that endures.