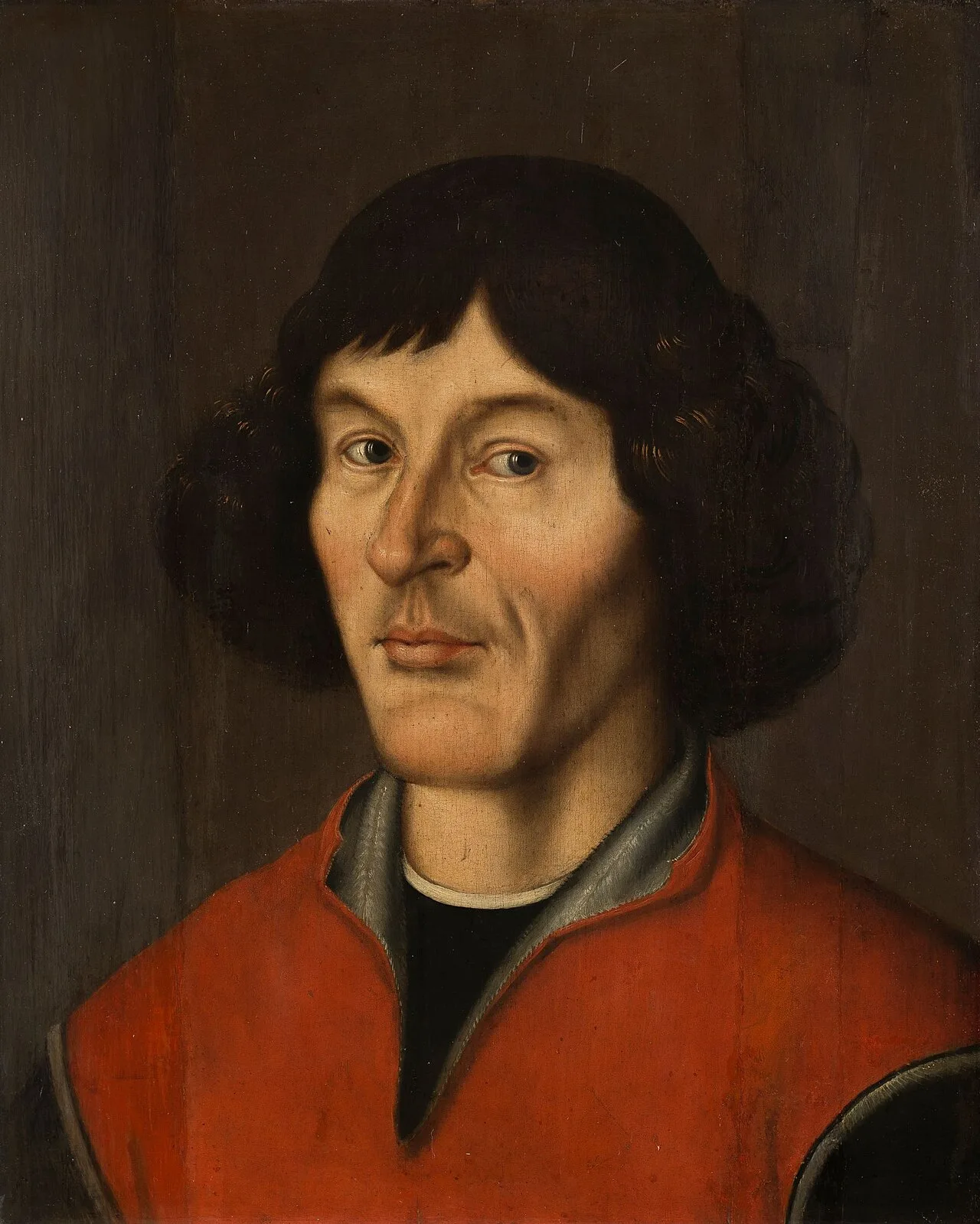

In the wintry shadow of February 19, 1473, in the small Polish city of Toruń, a child was born who would one day shake the very foundations of how humanity saw the cosmos. Nicolaus Copernicus arrived into a world still cloaked in medieval understanding, where Earth stood immovable at the center of the universe and the stars circled above like celestial angels. The sky, to most, was a perfect dome of divine design, unquestionable and eternal.

But not to Copernicus.

The son of a prosperous copper merchant and a mother descended from a family of urban patricians, young Nicolaus was born into relative comfort, though his life was destined to be anything but ordinary. Tragedy struck early—when he was just ten years old, his father died, leaving the boy and his siblings under the guardianship of their maternal uncle, Lucas Watzenrode. This was no minor twist of fate. Watzenrode, a powerful churchman and later bishop of Warmia, saw potential in his nephew and took great care to ensure the boy received the education befitting a scholar of promise.

From the very beginning, Nicolaus Copernicus gazed upward with more curiosity than reverence, more questioning than submission. The stars whispered riddles no priest could answer, and young Copernicus, quiet and unassuming, began a lifelong journey to unravel them.

Forming a Mind in the Cradle of Renaissance

As the fifteenth century neared its close, the Renaissance spread across Europe like wildfire, breathing life into art, science, and philosophy. Nicolaus Copernicus, now a young man, traveled first to the University of Kraków around 1491. There, immersed in the liberal arts, he was introduced to the astronomical teachings of Ptolemy, Aristotle, and the growing whispers of mathematical contradiction from thinkers like Regiomontanus.

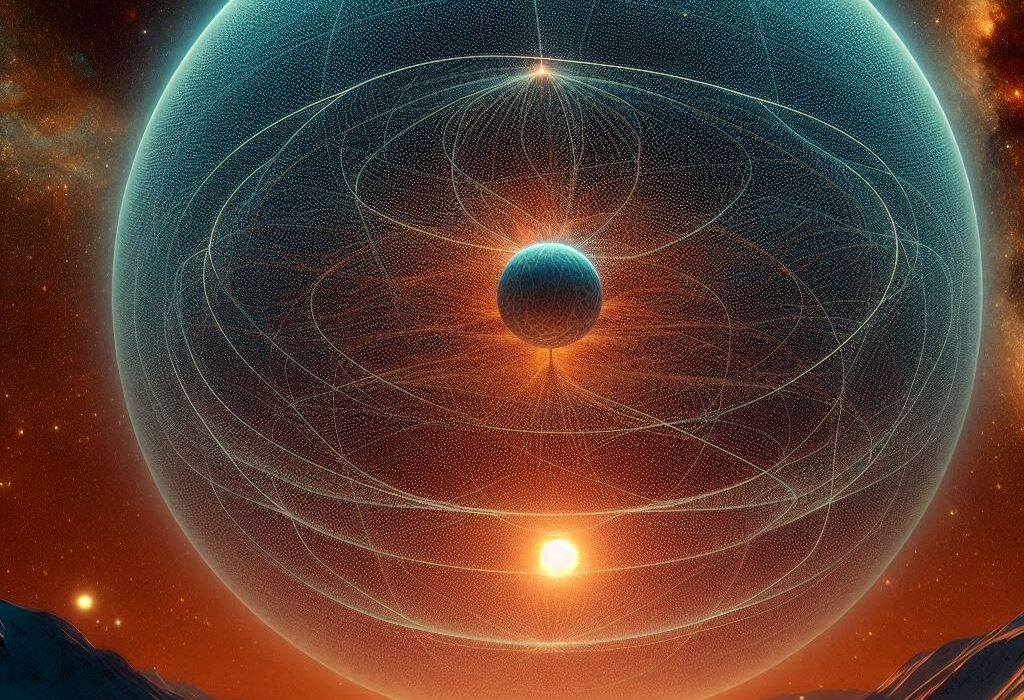

The curriculum at Kraków was deeply entrenched in the geocentric model, a framework that had reigned for nearly 1,500 years. In this model, Earth stood motionless at the center of a cosmos nested in perfect crystalline spheres. To Copernicus, the model was brilliant in form but deeply flawed in logic. Why should celestial bodies, supposed to move in circles, require so many strange fixes—epicycles, equants, deferents—just to explain their wandering paths? The stars did not dance to such convoluted choreography. There had to be a simpler truth.

After Kraków, his journey took him across Europe. With the encouragement and funding of his uncle, he enrolled at the University of Bologna in 1496 to study canon law, but astronomy drew him with irresistible gravity. There, he encountered Domenico Maria Novara, an astronomer who invited Copernicus to collaborate in observations. Together, they watched the heavens, and slowly the Ptolemaic illusion began to unravel further.

Later, he studied medicine at Padua and earned a doctorate in canon law from Ferrara, but these were stepping stones toward a deeper calling. Throughout this academic pilgrimage, Copernicus devoured the writings of classical astronomers, translated Greek texts, and gathered fragments of ancient and modern thought like a mosaic that only he could see forming.

A Silent Revolution Begins

Returning to Warmia in 1503, Copernicus began a quieter phase of life. Installed as a canon at the cathedral in Frombork, he was officially tasked with administrative duties for the Church. He dealt with land disputes, managed diocesan finances, and lived the calm, structured life of a church official. But in his modest tower above the Baltic coast, another world was unfolding.

By day, he wore the robes of clerical order; by night, he unraveled the stars.

It was there, high above the world, that Copernicus worked tirelessly, refining an idea that had germinated in his mind for years. What if the Earth was not the center? What if it moved? What if the Sun, brilliant and central, was the anchor around which everything else revolved?

He dared to reframe the cosmos itself—not with reckless iconoclasm but with quiet determination and mathematical precision. Copernicus observed the heavens through basic instruments—quadrants, armillary spheres, and naked eyes trained on stars—and tested his theory against the movement of planets.

He called this heliocentric model “more elegant,” not because it was beautiful in a decorative sense, but because it brought order to chaos. With it, the backward motion of planets—retrograde motion—was no longer an illusion created by epicycles, but a natural result of Earth’s own orbit overtaking others.

It was not just a different model. It was a different universe.

Fear, Doubt, and the Heavy Weight of Truth

Copernicus was no rebel. He did not pound fists on tables or shout from pulpits. He was a scholar of temperance and caution, and he knew the danger of his revelations. To question the Earth’s central position was not just to contradict Ptolemy—it was to challenge theology, Scripture, and centuries of scholastic doctrine. His model risked being seen not as a scientific refinement, but as heresy.

So he delayed.

He wrote a brief abstract of his heliocentric theory around 1514, called the Commentariolus, and shared it privately among trusted colleagues. It stirred interest and admiration in some quarters and caution in others. Yet, even as evidence grew, Copernicus held back from publishing a full account. For more than two decades, the manuscript that would become his magnum opus remained unfinished, its author caught in a struggle between intellectual integrity and existential risk.

In those years of delay, he refined his arguments and deepened his calculations, even as the world around him changed. Martin Luther’s Reformation was tearing Europe apart, and the Church, increasingly defensive, watched for dissent not only in religion but in all fields of thought. Copernicus lived on the knife-edge between genius and damnation.

Yet the universe did not wait. The stars spun, the planets danced, and the truth became impossible to hold in silence.

De Revolutionibus: The Book That Changed Everything

The year was 1543. Nicolaus Copernicus was nearing the end of his life. Ill and weakened by a stroke, he knew his time was short. Encouraged by a young mathematician and astronomer named Georg Joachim Rheticus, who had studied under him and passionately believed in his ideas, Copernicus finally agreed to publish his life’s work.

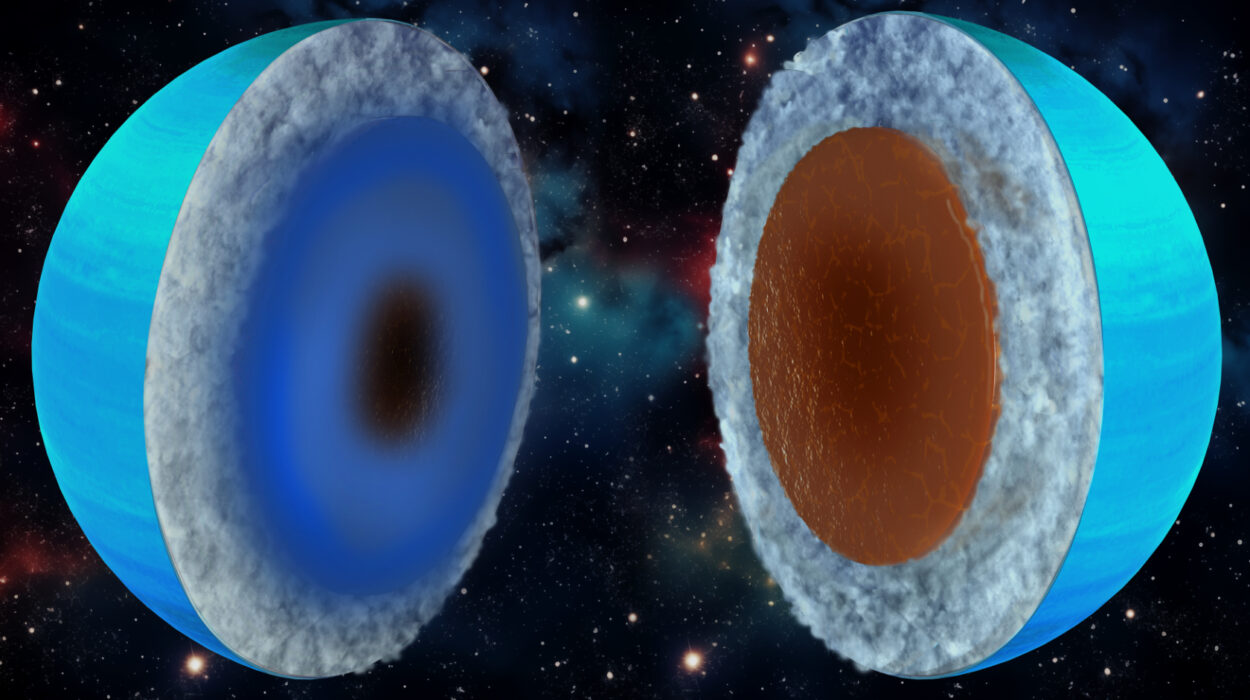

That year, De revolutionibus orbium coelestium (On the Revolutions of the Celestial Spheres) went to print. In six dense books, Copernicus laid out a new architecture of the cosmos. The Sun stood motionless at the center, and Earth—our seemingly solid, still world—spun on its axis and orbited the Sun with the rest of the planets.

The book was cautious in tone, thick with mathematical proofs and astronomical data. The preface, added without Copernicus’s approval by the Lutheran theologian Andreas Osiander, presented the heliocentric model as a mere mathematical tool, not a physical reality—an act of self-preservation more than honesty.

Still, the truth could not be hidden. Copernicus had moved the Earth.

According to legend, a copy of his book was placed in his hands on his deathbed. He awoke briefly, saw it, and smiled. On May 24, 1543, Nicolaus Copernicus died in Frombork, the Sun shining above a world that was no longer the center of the universe.

The Earth Moves Slowly, and So Does Truth

The publication of De revolutionibus did not set the world ablaze—at least not immediately. For decades, the book circulated quietly among scholars. Many praised its mathematical elegance but hesitated to accept its physical implications. Tycho Brahe, a later Danish astronomer, developed his own geo-heliocentric model, combining Copernican math with a traditional Earth-centered system.

But the seeds had been planted. Galileo Galilei would later take up Copernicus’s banner, using telescopes to observe moons orbiting Jupiter and the phases of Venus—evidence impossible to reconcile with Ptolemaic cosmology. Galileo’s public endorsement of the Copernican model brought down the wrath of the Inquisition, and De revolutionibus was eventually placed on the Index of Forbidden Books in 1616.

Yet the truth had already begun its slow revolution. Johannes Kepler, building on both Copernicus and Brahe, refined the model with elliptical orbits. Isaac Newton, more than a century later, would give the entire system the mathematical foundation of universal gravitation.

All of them stood on the shoulders of the quiet canon from Poland who looked at the heavens and saw something the world could not yet bear to accept: motion where others saw stillness, order where others saw chaos.

A Legacy That Outlived the Stars

Today, we measure our years by a calendar shaped by heliocentric understanding. Our satellites, space probes, and GPS systems operate on principles that would be unthinkable without the Copernican model. Yet the deeper impact of Nicolaus Copernicus was not just scientific—it was existential.

He displaced humanity from the center of the universe, forcing us to confront a cosmos vast beyond imagining. It was a humbling blow, and for many, a terrifying one. But it was also the birth of modern science: a method that valued observation, calculation, and the courage to overturn even the oldest truths.

Copernicus’s life reminds us that revolutions do not always come with fire and fury. Some arrive with silence and patience, with ink and paper, with a steady gaze at the night sky. His story is not one of drama or martyrdom but of quiet bravery and the relentless pursuit of truth.

He was not the first to imagine the Sun at the center—ancient Greek thinkers like Aristarchus had suggested it centuries earlier—but he was the first to do so with mathematical rigor and persuasive evidence, and to create a framework that others could build upon. He did not demand belief; he invited understanding.

The Man Behind the Model

Nicolaus Copernicus was never married, never known for political speech, never a firebrand or revolutionary in personality. He lived most of his adult life in relative obscurity, far from the courts of kings or the bustling centers of power. He never built a telescope, never traveled far, never heard the applause of crowds.

And yet, from his modest perch above the world, he saw farther than almost anyone before him.

His personality, as described by those who knew him, was reserved, even austere. But within him burned a furnace of intellectual passion. He worked alone not by choice but by necessity. The task he undertook was monumental, and few dared to walk beside him. He did not seek glory; he sought understanding.

And in that quest, he gave the world a new frame through which to see not just the stars, but ourselves.