Under the silent watch of an extinct volcano in northeastern Spain, a tiny creature lay undisturbed for more than three million years. Entombed in fine lakebed sediments, its delicate bones held secrets that would one day challenge what scientists thought they knew about continents, creatures, and the hidden highways of Earth’s past.

That creature—an ancient mole with a taste for tunnels and perhaps even swimming—has finally stepped into the spotlight. And it carries a name as dramatic as the place it called home: Vulcanoscaptor ninoti, the “volcano digger of Camp dels Ninots.”

A Gem Unearthed From Volcanic Ashes

The story of Vulcanoscaptor ninoti begins in the Pliocene Epoch, over 3.5 million years ago. The landscape of southern Europe was alive with animals and verdant forests, under skies that hinted at the coming ice ages. In a region now known as Camp dels Ninots—literally “Field of the Dolls”—an explosive maar volcano had punched a crater into the earth, which slowly filled with a quiet lake.

Into that lake fell leaves, pollen, and the occasional unlucky animal. Over millennia, silt and volcanic ash preserved them in an oxygen-starved tomb. This unique cocktail of geology and chemistry turned Camp dels Ninots into one of Europe’s greatest fossil treasure troves.

And it’s there that researchers found the ancient mole.

“This is one of the oldest and most complete mole fossils ever discovered in Europe,” says Adriana Linares, lead author of the new study published in Scientific Reports. “Finding such a delicate, small animal in this exceptional state of preservation is almost miraculous.”

The Tiny Traveler From a Distant Land

When Linares and her colleagues from IPHES-CERCA, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, and Institut Català de Paleontologia Miquel Crusafont examined the mole’s fossilized bones, they were astonished. This wasn’t just any European mole. Its anatomy placed it firmly in a group called Scalopini—moles today found only in North America and parts of Asia.

“Despite its clearly fossorial morphology, this mole is closely related to extant North American species of the genera Scapanus and Scalopus,” says Dr. Marc Furió, co-author of the study. “This points to a far more intricate evolutionary history for these animals than we had imagined.”

For decades, scientists believed moles were creatures of limited travel—a specialized group with poor dispersal abilities, living in isolated patches. Yet Vulcanoscaptor ninoti tells a different story. At some point, moles must have crossed ancient land bridges between continents. Whether they trekked through Asia, Europe, and North America, or migrated across Beringia when sea levels were low, remains a tantalizing puzzle.

Its presence in Pliocene Europe suggests transcontinental migrations of moles far earlier and more complex than anyone suspected.

A Window Into a Tiny Engineer’s Life

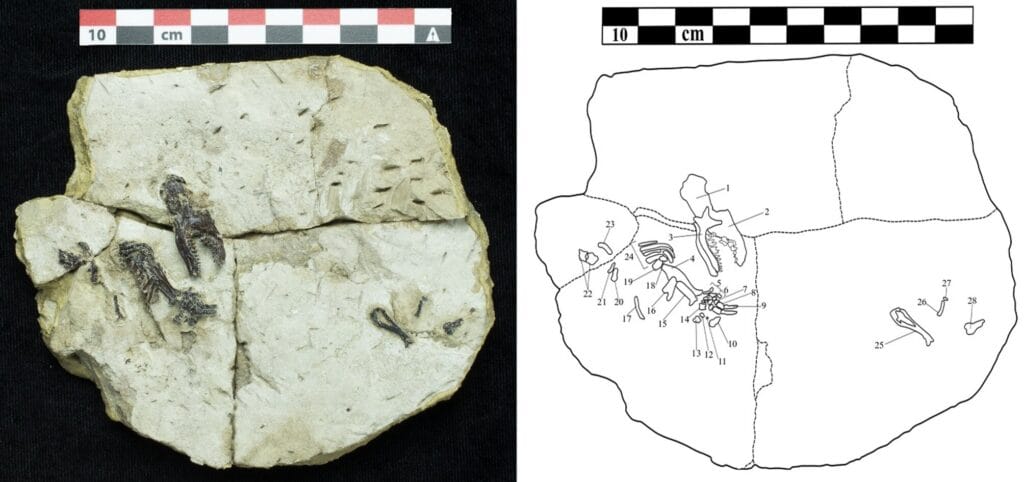

The fossil, unearthed in 2010, is nothing short of spectacular for paleontologists who usually work with fragments. It includes a complete mandible with teeth, parts of the torso, and numerous limb bones—some still connected in anatomical position.

It wasn’t easy to study, though. Encased in dense sediment, the bones were fragile, delicate as porcelain. So scientists turned to a high-tech solution: microCT scanning.

“With the microCT, we were able to analyze extremely small and delicate structures—such as phalanges and teeth—that would have been nearly impossible to study otherwise,” Linares explains. “It allowed us to identify unique anatomical features and confirm the placement of this new species within the Scalopini.”

The digital scans revealed robust front limbs, built for digging. The humerus was thick and powerful, lined with ridges for muscle attachment, while the mole’s broad paws were perfect shovels for moving soil.

Yet there was another twist.

A Mole That Might Have Swum?

Although this mole was a master digger, its final resting place raises intriguing questions. Its skeleton was found in lacustrine sediments, suggesting it may have died in or near a lake.

“Modern moles are sometimes excellent swimmers, even though they’re primarily subterranean,” says Linares. “We can’t confirm aquatic abilities yet for Vulcanoscaptor ninoti, but the possibility is fascinating.”

Could this mole have slipped through water, hunting insects or escaping predators, before meeting its end? For now, the fossil leaves only hints.

Camp dels Ninots: Where Time Stands Still

Camp dels Ninots isn’t just a random spot on the map. It’s a geological wonder. Declared a Cultural Asset of National Interest by the Government of Catalonia, it’s an ancient lake bed inside a volcanic crater, perfectly preserved thanks to anoxic conditions that prevented decay.

“The quality and diversity of the fossil record here are extraordinary,” says Dr. Gerard Campeny, co-director of the excavations. “It allows us to reconstruct entire ecosystems from the Pliocene.”

From giant tapirs to ancient rhinos, birds, amphibians, fish, and now a mole that traveled continents, Camp dels Ninots offers a rare glimpse into a vanished world.

“Discoveries like Vulcanoscaptor ninoti would not be possible without the combination of an exceptional geological setting and rigorous, interdisciplinary research,” adds Dr. Bruno Gómez de Soler, another co-director. “It’s an inexhaustible source of scientific knowledge.”

Digging Deeper Into Our Shared History

The arrival of Vulcanoscaptor ninoti in the fossil record rewrites chapters in mole evolution—and in how animals navigated Earth’s shifting continents.

Small as it was, this mole carried the legacy of ancient migrations and hidden corridors between worlds. It reminds us that Earth’s history is stitched together not just by giant beasts, but also by the quiet engineers underground, whose tunnels span both soil and time.

As paleontologists continue excavations at Camp dels Ninots, who knows what other secrets lie waiting beneath the volcanic ash? Perhaps more creatures that crossed oceans and mountains long before humans ever dreamed of maps.

Reference: Adriana Linares-Martín et al, An unexpected Scalopini mole (Talpidae, Mammalia) from the Pliocene of Europe sheds light on the phylogeny of talpids, Scientific Reports (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41598-025-10396-1