In a world once ruled by giant reptiles and the shadows of swooping wings, a small flying creature carried a secret in its belly—a secret that has taken over a hundred million years to finally come to light.

New research has uncovered the first direct evidence that pterosaurs—the Mesozoic’s masters of the skies and the earliest vertebrates to achieve powered flight—weren’t just fearsome hunters snatching fish from prehistoric seas. At least some of them were also munching on plants.

The discovery is reshaping our understanding of these remarkable animals, suggesting that the skies of the dinosaur age were navigated not only by predators, but by creatures whose diets were far more varied—and maybe far greener—than anyone suspected.

A Mystery That Spanned the Skies

For decades, paleontologists have debated what pterosaurs actually ate. These iconic reptiles, with wingspans ranging from a few feet to over thirty feet, soared over Jurassic and Cretaceous landscapes, leaving behind spectacular fossils—but few concrete clues about their dinner plans.

Some scientists argued that pterosaurs were fish-hunters, diving and skimming over the water’s surface like modern seabirds. Others proposed diets of insects, small animals, or even plants. There were hypotheses that some species filtered tiny organisms from the water, similar to flamingos today. Until now, most of these ideas rested on indirect evidence—like the shape of a pterosaur’s beak or the wear on its teeth.

Occasionally, tantalizing hints surfaced: fish bones lodged in a pterosaur’s gut, insect parts found in fossilized droppings. Yet the notion that pterosaurs might have enjoyed a leafy snack remained speculative at best.

A Fossil With a Story to Tell

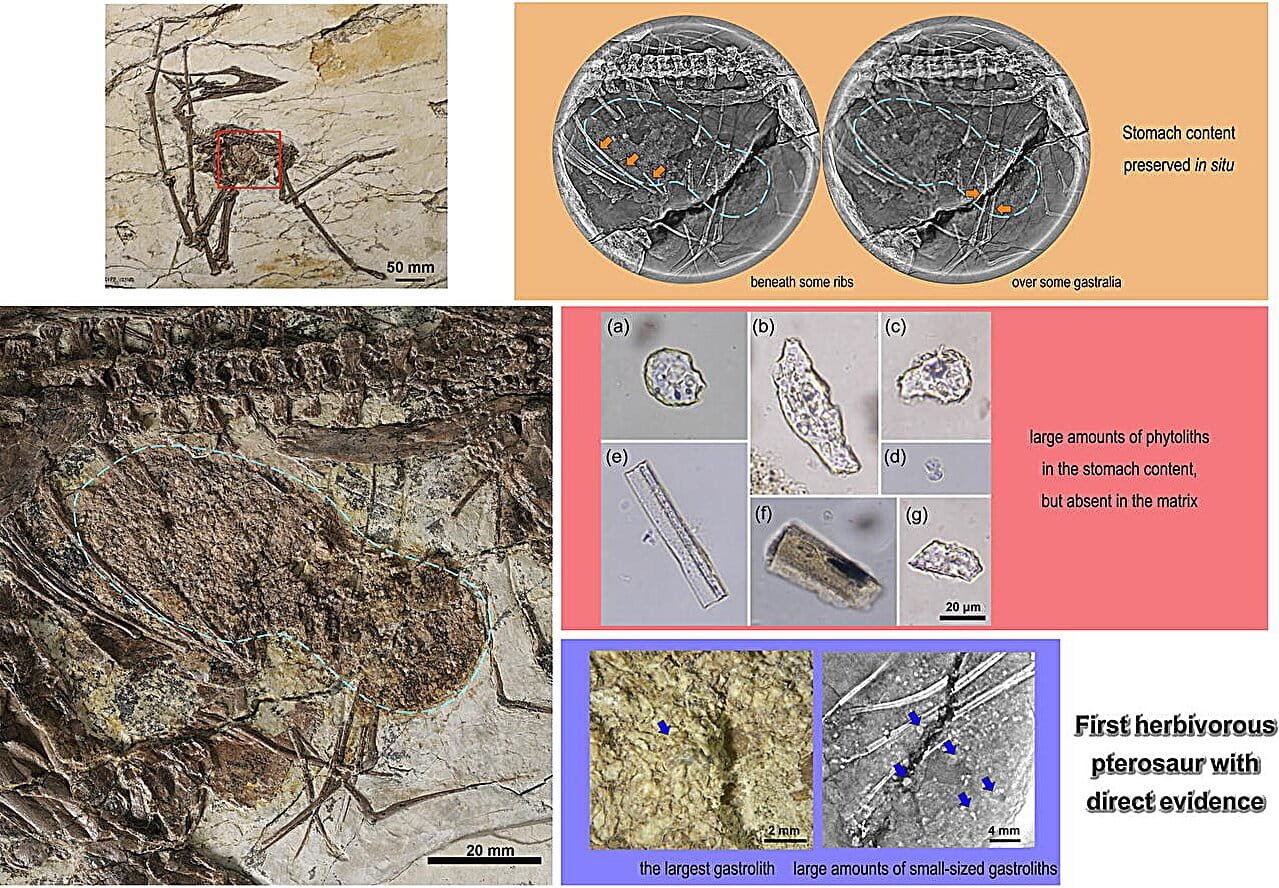

That changed with a remarkable find from the Lower Cretaceous Jiufotang Formation in western Liaoning, China—a treasure trove of fossils from roughly 120 million years ago. Here, scientists uncovered the exquisitely preserved remains of a young pterosaur called Sinopterus atavismus.

Not only was this fossil nearly complete—its wings, bones, and delicate features frozen in stone—but inside its fossilized ribcage lay the unmistakable contents of its last meal.

Embedded in the rock were tiny silica particles called phytoliths—microscopic structures formed within plant cells. Phytoliths are remarkably durable and can survive long after leaves and stems have decayed, offering a botanical fingerprint of ancient vegetation.

Phytoliths have been found before in the stomachs of plant-eating dinosaurs. But until this discovery, none had ever been detected in a pterosaur. Their presence inside Sinopterus is a stunning revelation.

A Stone’s Digestive Throwback

Alongside the phytoliths, scientists found gastroliths—small stones swallowed by some animals to help grind tough plant fibers in their stomachs. Many modern birds, like ostriches and parrots, still use this digestive strategy. Their presence in Sinopterus further bolsters the idea that at least some pterosaurs were herbivores.

In total, researchers extracted more than 320 phytoliths from the specimen. Yet identifying exactly which plants these ancient particles belonged to is no simple task. The diversity of plant life in the Cretaceous was vast—and the science of matching fossil phytoliths to specific species is still developing.

“The phytolith morphologies in the stomach contents, with this high diversity, are nearly impossible to attribute to one single taxon based on the recent knowledge,” the scientists wrote in their report in Science Bulletin. “This suggests that Sinopterus might have consumed a diverse range of plants.”

A Broader Pterosaur Menu

This groundbreaking discovery doesn’t mean that all pterosaurs were vegetarian. The group was astonishingly diverse, encompassing countless species with a wide range of sizes, habitats, and anatomical specializations. It’s likely that different pterosaurs filled many ecological niches, from fearsome fish-hunters to gentle herbivores.

Still, Sinopterus atavismus has provided the first indisputable proof that some pterosaurs happily dined on plant material—a revelation that dramatically expands our picture of pterosaur ecology.

The Search Continues

Paleontologists are buzzing with new questions. How widespread was plant-eating among pterosaurs? Did different species specialize in different kinds of vegetation? Could some have shifted their diets seasonally?

One thing is certain: fossils like Sinopterus are rare, and the odds of finding more specimens with perfectly preserved stomach contents are slim. But researchers remain hopeful that more fossils will surface—perhaps hiding further secrets of prehistoric meals.

“This discovery provides a window into the complexity of ancient ecosystems,” said Dr. Bader, who was not directly involved with the study but commented on its significance. “It reminds us that even creatures we thought we knew well can surprise us.”

Beyond the Predator’s Shadow

For over a century, the image of pterosaurs has leaned heavily toward the dramatic: sharp-beaked predators silhouetted against Cretaceous skies. Now, thanks to a small fossil from Liaoning, we glimpse a softer side of these aerial reptiles—a reminder that life, even in the age of dinosaurs, was full of unexpected tastes.

Sinopterus atavismus, the little pterosaur with a bellyful of plants, stands as testament to the idea that evolution’s stories are rarely simple—and that sometimes, history’s most astonishing revelations come from the quiet crunch of leaves between prehistoric teeth.

Reference: Shunxing Jiang et al, First occurrence of phytoliths in pterosaurs—evidence for herbivory, Science Bulletin (2025). DOI: 10.1016/j.scib.2025.06.040