Deep inside the labyrinth of the human brain, a silent storm may begin decades before memories slip away or names vanish from our grasp. Alzheimer’s disease, the relentless thief of cognition, has long been thought of as a specter of old age. Yet new research out of Finland is revealing a striking truth: the seeds of Alzheimer’s might already be sprouting in middle-aged brains—and the key to spotting them could lie in a simple vial of blood.

In a sweeping new study published in The Lancet Healthy Longevity, scientists from the University of Turku have found that blood-based biomarkers linked to Alzheimer’s disease can be detected in people as young as their early forties. The discovery opens the door to a future where early detection—and potentially, prevention—could transform the fight against one of humanity’s most devastating neurological diseases.

Silent Shadows of Alzheimer’s in Middle Age

Alzheimer’s disease is not merely a condition of elderly minds. While confusion, memory loss, and personality changes typically appear later in life, the biological processes that cause these symptoms—like the buildup of beta-amyloid plaques and tau tangles—often begin invisibly, years or even decades earlier.

Now, evidence is growing that those invisible changes can leave measurable traces in our blood far earlier than once thought.

“Until now, brain biomarkers associated with Alzheimer’s disease have mainly been studied in older individuals,” says Marja Heiskanen, senior researcher at the Research Center of Applied and Preventive Cardiovascular Medicine at the University of Turku. “Our study provides new insights into biomarker levels and associated factors starting from middle age.”

The research is part of the long-running Cardiovascular Risk in Young Finns Study, which has tracked thousands of individuals for decades to illuminate how early-life health affects disease risk in adulthood. For this Alzheimer’s investigation, researchers analyzed blood samples from 2,051 participants between 41 and 56 years old—and from their parents, aged 59 to 90.

Blood: A New Window Into the Brain

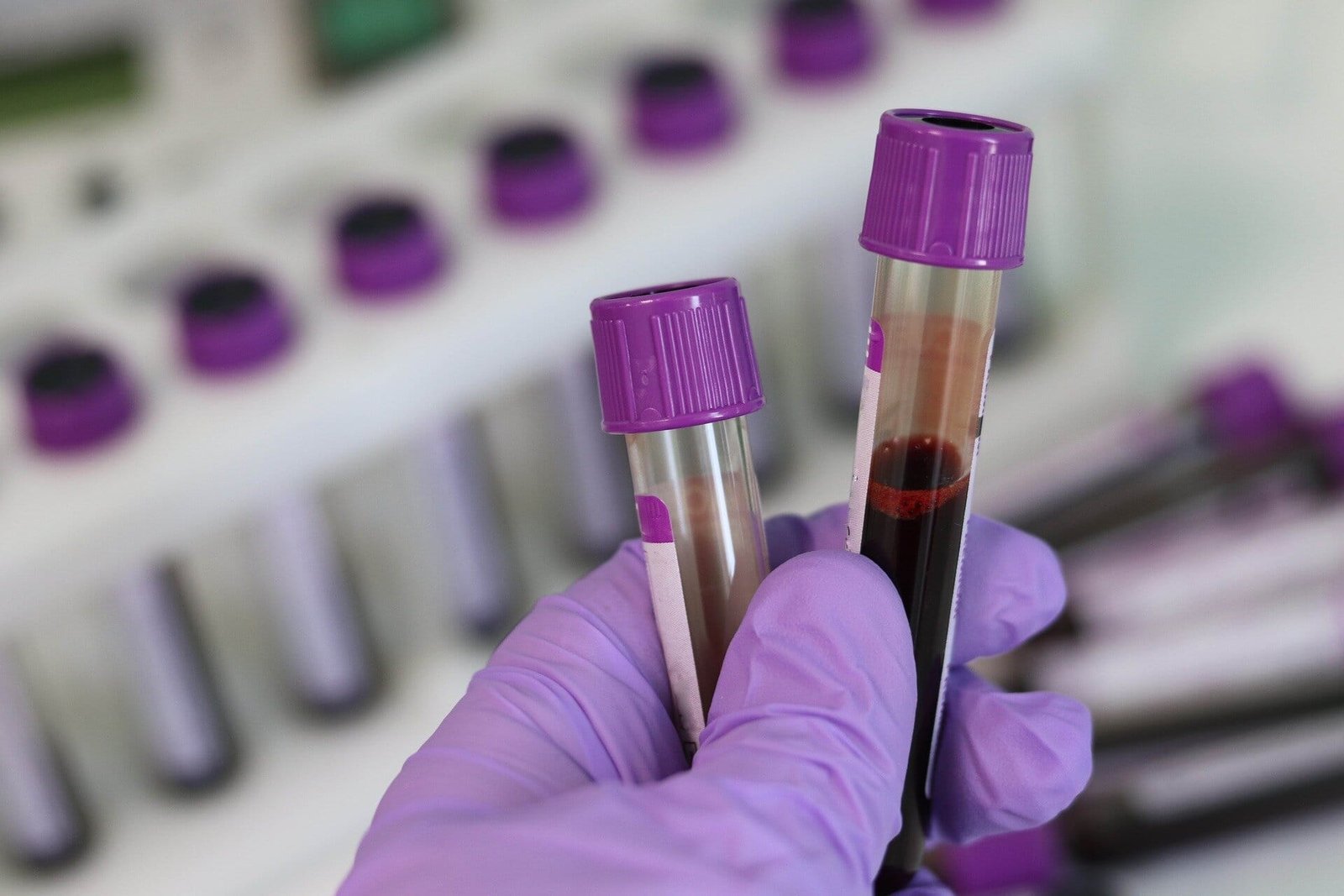

Traditionally, confirming Alzheimer’s disease has required invasive procedures like spinal taps to analyze cerebrospinal fluid or costly brain imaging scans. But in recent years, advances in ultrasensitive detection methods have made it possible to measure certain brain-related proteins directly from blood samples.

“In clinical practice, detecting beta-amyloid pathology associated with Alzheimer’s disease currently requires imaging studies or cerebrospinal fluid sampling,” explains Suvi Rovio, senior researcher and lead author of the study. “However, recently developed ultrasensitive measurement technologies now allow the detection of Alzheimer’s disease-related brain biomarkers from blood samples.”

It’s a potential game-changer. Blood tests are far cheaper, less invasive, and more accessible than current diagnostic tools. They could help identify people at highest risk of Alzheimer’s years before symptoms strike—while there’s still time for interventions to slow or prevent the disease’s progression.

Family Ties and Hidden Risks

One of the study’s most intriguing findings lies in the echoes of Alzheimer’s risk passed from parent to child. Researchers discovered that if a parent—particularly a mother—had elevated blood biomarkers linked to Alzheimer’s disease, their middle-aged offspring were more likely to have elevated levels as well.

This suggests that genetic or shared environmental factors could influence the biological processes that set Alzheimer’s in motion decades before any clinical signs emerge.

In addition, the study revealed a link between kidney disease and higher Alzheimer’s-related biomarker levels in middle age. The connection hints at how systemic health conditions might interact with brain health, potentially amplifying risks for dementia later in life.

Curiously, the study also examined the influence of the APOE ε4 gene—the strongest known genetic risk factor for late-onset Alzheimer’s. While older individuals carrying this gene showed higher levels of Alzheimer’s biomarkers, no such connection appeared yet in middle-aged participants.

Promise and Caution in Equal Measure

Although the results are groundbreaking, scientists urge caution. Measuring Alzheimer’s risk through blood is still an emerging science, and there’s much to learn before it can be used confidently in clinics.

“It is not yet possible to definitively diagnose Alzheimer’s disease with a blood sample,” Rovio emphasizes. “The method is still limited by the lack of well-known reference values. Additionally, it remains unclear which confounding factors influence biomarker concentrations in blood related to Alzheimer’s disease.”

For now, the blood biomarkers serve as tantalizing clues rather than definitive proof. Misinterpretation could lead to unnecessary anxiety—or even misdiagnosis. To avoid this, researchers stress the importance of further studies across diverse populations and age groups to establish clear standards.

“In order to reliably use blood-based biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease diagnosis in the future, more research is needed across different populations and age groups to standardize reference values,” Rovio adds.

A Glimpse Into the Future of Alzheimer’s Care

Despite the challenges, the implications of these findings are profound. If doctors can reliably detect Alzheimer’s disease in its earliest biological stages, they could intervene sooner—potentially delaying the onset of symptoms or reducing the disease’s severity.

As the global population ages, the number of people affected by Alzheimer’s and related dementias is projected to soar. Early detection through blood tests could offer a crucial lifeline, shifting the narrative from reactive treatment to proactive prevention.

For now, the study from Finland is a reminder that Alzheimer’s disease is not merely a sudden thief in old age—it’s a silent process unfolding over decades. And in the crimson swirl of a blood sample, scientists are beginning to see the faint outlines of its earliest shadows.

Reference: Factors related to blood-based biomarkers for neurodegenerative diseases and their intergenerational associations in the Young Finns Study: a cohort study. The Lancet Healthy Longevity. DOI: 10.1016/j.lanhl.2025.100717