For generations, our image of dinosaurs has been shaped by cinema—massive, scaly monsters thundering across the screen, unleashing guttural roars that shake the Earth. These cinematic titans, immortalized by Hollywood in films like Jurassic Park, seem frozen in a particular vision of the past: one of reptilian terror, primitive strength, and prehistoric silence broken only by fearsome growls.

But as paleontology progresses, that vision is rapidly unraveling. Fossil by fossil, science is sketching a very different portrait of the dinosaurs that once ruled Earth. Not just hunters and grazers, but complex, often delicate creatures—some cloaked in feathers, some sporting vibrant colors, and, perhaps most surprisingly of all, some that may have sung.

Yes, dinosaurs might not have roared—they might have chirped, whistled, or even tweeted.

A Dragon in Bird’s Clothing

High in the forested cliffs of northern China, in a region once teeming with ancient life, scientists made a discovery that has begun to reshape what we know about dinosaur communication. The fossil of a small, herbivorous dinosaur, just two feet long, emerged from the reddish stone of the Upper Jurassic Tiaojishan Formation. Its name—Pulaosaurus qinglong—honors Pulao, a mythical Chinese dragon said to cry out with a voice so loud it could rattle mountains.

But Pulaosaurus, despite its legendary name, may have made a very different kind of sound.

Unlike the imagined thunderous bellows of tyrannosaurs or the deep, resonant growls of Hollywood raptors, Pulaosaurus might have produced high-pitched, bird-like vocalizations. Whistles. Trills. Even songs.

The secret lies in its throat.

Fossils with a Voice

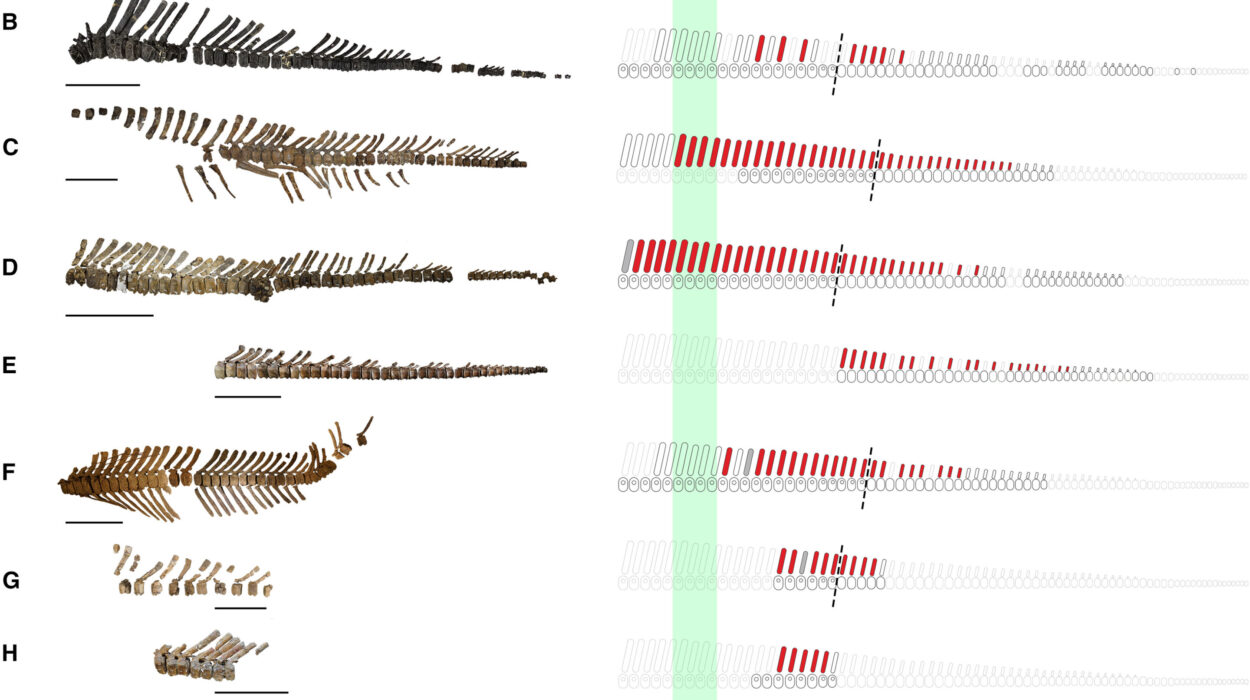

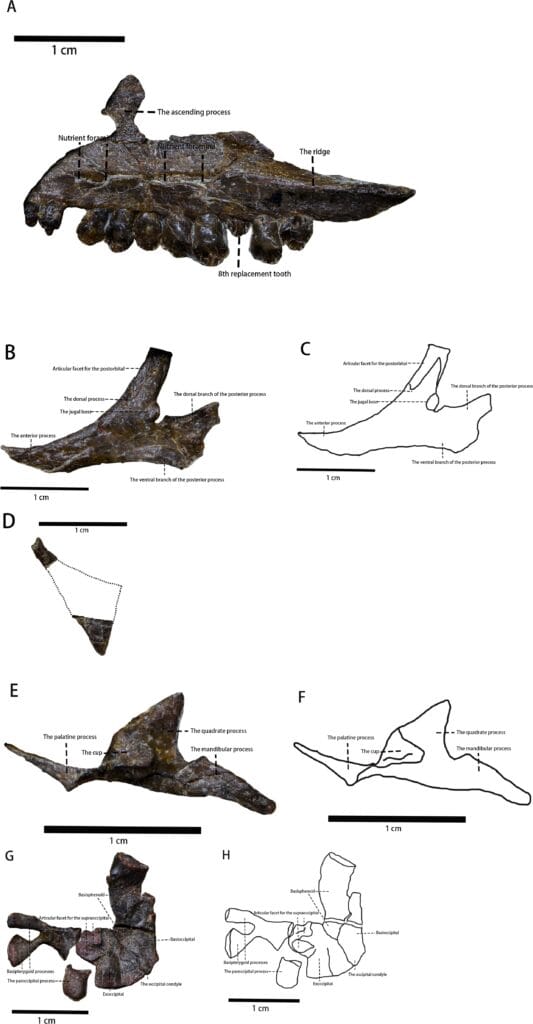

The fossilized remains of Pulaosaurus were astonishing in their completeness. Nearly the entire skeleton was preserved: the vertebrae curled in their ancient posture, the limbs still articulated, the jaw set in a long-forgotten bite. But among the bones were rarities rarely seen in dinosaurs—parts of the larynx, the very structure involved in sound production.

Only one other dinosaur has ever been found with fossilized larynx bones, making this discovery exceptionally precious. It gave researchers something they’ve longed for: a glimpse into how dinosaurs may have sounded.

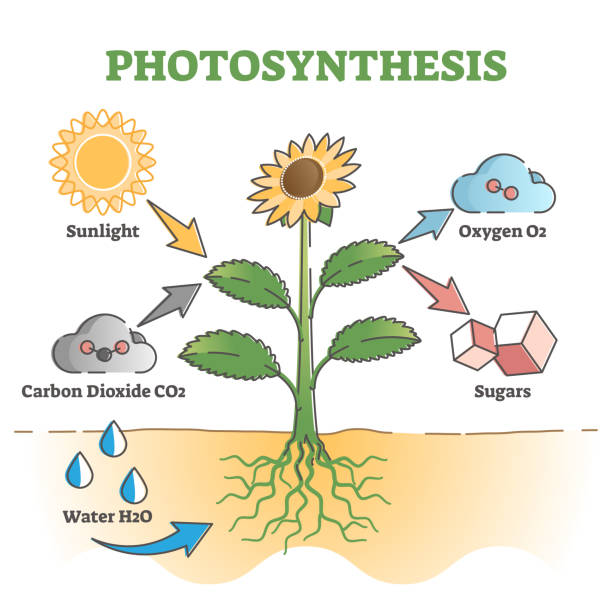

Careful analysis revealed that Pulaosaurus’s larynx contained elongated, leaf-shaped structures made of cartilage—similar in shape to the laryngeal structures found in today’s birds. In birds, these structures vibrate and resonate, producing a wide range of calls. From the raucous squawks of parrots to the ethereal songs of nightingales, the bird voice box is a marvel of evolutionary engineering.

Could it be that Pulaosaurus had a voice as well?

The Birds Within

Birds are, in fact, living dinosaurs. That’s not poetic analogy—it’s biological truth. Over the last few decades, genetic, anatomical, and fossil evidence has confirmed that modern birds evolved from small theropod dinosaurs, cousins of the same lineage that gave rise to T. rex and Velociraptor. But Pulaosaurus was something else: a member of the Neornithischia, a subgroup of the Ornithischia—the “bird-hipped” dinosaurs.

These were herbivores, often equipped with beaks and teeth designed to chomp on plants. Their evolution diverged early from that of the carnivorous theropods, but the similarities in their larynx suggest convergent evolution—an instance where different evolutionary paths arrive at similar solutions.

The discovery doesn’t mean all dinosaurs tweeted or sang. Sound production can vary widely even among modern reptiles and birds. Crocodiles grunt, frogs croak, and birds serenade. Dinosaurs likely had a spectrum of sounds too—some deep, some shrill, some perhaps silent. But Pulaosaurus, small and possibly social, might have communicated with others through short, musical calls—much like sparrows in a tree.

More Than a Voice: A Window into the Past

Beyond the vocal structures, the Pulaosaurus fossil offered other treasures. Inside its fossilized torso, in what once was its stomach, researchers discovered tiny, rounded pebbles—known as gastroliths. These stones, swallowed by some dinosaurs and modern birds, helped grind up plant material in the digestive tract. Alongside them were impressions that may have been seeds or soft plant tissue—evidence of what the animal ate before it died.

Its jaw and teeth supported this picture. Broad and leaf-shaped, the teeth were ideal for slicing soft vegetation. Its tongue, inferred from skeletal clues, may have helped it manipulate food like a modern parrot or goose. Altogether, Pulaosaurus appears to have been a peaceful plant-eater, more interested in ferns and shoots than in fighting.

But its most profound gift wasn’t in its teeth or stomach—it was in the clues it carried about how dinosaurs communicated, how they interacted, how they may have called to one another across the forests of ancient China.

Echoes from the Yanliao Biota

The area where Pulaosaurus was found—known as the Yanliao Biota—is a treasure trove of Jurassic fossils. Preserved in exquisite detail thanks to fine volcanic ash and rapid burial, this region has revealed creatures from a long-vanished world: early birds, ancient fish, proto-mammals, and feathered dinosaurs.

But until now, most discoveries here focused on small theropods and early birds, leaving herbivorous dinosaurs like Pulaosaurus in the shadows. The fossil helps fill a critical gap in our understanding of early neornithischian evolution, bridging a missing chapter in the story of how plant-eating dinosaurs diversified and thrived.

This new species is more than a name in a scientific paper—it’s a living thread in the tapestry of life’s history, one that connects past to present in ways both unexpected and poetic.

Songs of a Lost World

It is strangely beautiful to think of Pulaosaurus—a small, bird-hipped dinosaur—standing in the underbrush of a Jurassic forest, calling out in high, clear notes to others of its kind. Perhaps it used those sounds to warn of danger, to court a mate, or simply to stay in touch with its herd. Perhaps its calls echoed through ferns and cycads, across volcanic hills, under the stars of a younger Earth.

For so long, we imagined dinosaurs only as monsters. But Pulaosaurus reminds us that they were something far more nuanced. They were animals, rich with behaviors and adaptations. They may have been gentle. They may have sung.

And as we uncover more fossils, as new tools like CT scanning and chemical analysis reveal hidden details, we will keep rewriting the ancient narrative—not just with bones and teeth, but with voice.

A New Vision, A New Voice

The story of Pulaosaurus qinglong challenges us to expand our understanding of what dinosaurs were—and who they were. Not merely beasts of scale and muscle, but creatures capable of communicating in ways that resonate with our own.

It’s a reminder that science isn’t about confirming what we think we know—it’s about asking new questions, daring to imagine new truths, and listening, even across millions of years, for voices we never expected to hear.

As paleontologists dig deeper, one truth becomes clearer with every discovery: dinosaurs never truly left us. They fly above us as birds. They live in our genes. And sometimes, through fossils like Pulaosaurus, they speak again—not in roars, but in whispers. In songs. In the language of life, echoing from a forgotten world.

Reference: Yunfeng Yang et al, A new neornithischian dinosaur from the Upper Jurassic Tiaojishan Formation of northern China, PeerJ (2025). DOI: 10.7717/peerj.19664