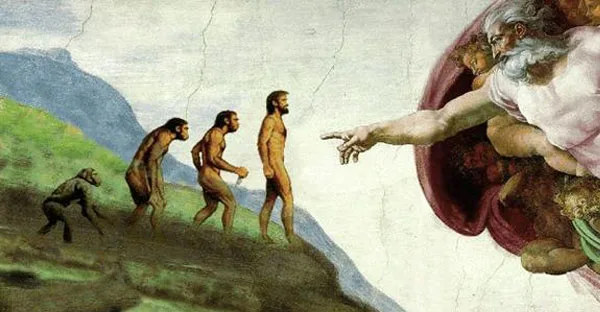

For centuries, the story of our existence has been told through the lenses of both science and faith. One speaks in equations, fossils, and genes; the other in parables, sacred texts, and prayer. And somewhere in the long, winding corridors of human thought, evolution and religion came to be seen not as companions in a shared search for truth—but as rivals in a bitter contest over the soul of humanity.

To many, the theory of evolution by natural selection represents the triumph of scientific inquiry. It provides a powerful explanation for the dazzling variety of life on Earth and traces our own species back to a shared ancestry with all living things. Yet for others, particularly within traditional religious communities, evolution seems to pose a threat: to purpose, to morality, to the sacred story of divine creation.

But must we choose? Must belief in God stand in opposition to belief in Darwin’s great idea? Or can evolution and religion, two of the most profound narratives ever conceived, find common ground? Beneath the clamor of culture wars and the noise of public debates lies a deeper, quieter question—one that touches not just the mind, but the heart: can these two ways of seeing the world coexist?

Understanding the Heart of Evolution

Before we can ask whether religion and evolution are compatible, we must first understand what evolution actually says—and what it doesn’t.

At its core, evolution is the process by which life changes over time. Through variation, inheritance, and natural selection, organisms adapt to their environments. Over millions of years, small genetic changes accumulate, giving rise to new species. The central idea, proposed by Charles Darwin in 1859 and refined by generations of scientists, is that all life on Earth shares a common ancestor.

Importantly, evolution is not a statement about purpose or morality. It does not claim that life is meaningless or that humans are insignificant. It does not pronounce on the existence of God. Rather, it is a scientific framework—a way to explain observable patterns in nature.

Evolution is supported by an overwhelming body of evidence from fields like paleontology, genetics, embryology, and comparative anatomy. It is not a guess or a hunch. It is one of the most robust theories in science, constantly tested and refined.

And yet, despite its scientific strength, evolution has been misunderstood, misrepresented, and resisted—especially when it is perceived to conflict with religious teachings about creation.

The Fear of Displacement

Part of the resistance to evolution comes from a deeper psychological and emotional place: the fear of displacement. For much of human history, religious traditions have taught that we are special, created in the image of God, placed at the center of creation with a divine purpose. The Genesis story in the Judeo-Christian tradition, for example, tells of a God who forms humans from dust, breathes life into them, and gives them stewardship over the Earth.

In contrast, evolution suggests that humans arose from a long line of animals, shaped by the blind forces of nature. It places us not above creation, but within it—a twig on the vast tree of life.

To some, this feels like a loss. If we are not uniquely created, does that mean we are accidents? If morality and consciousness evolved, are they mere illusions? If death and struggle are built into the fabric of life, how can we reconcile that with a loving God?

These are not trivial questions. They go to the heart of our identity, our hopes, our fears. They are not answered easily by facts or fossil records. And they deserve to be approached with empathy, not arrogance.

The Historical Conflict: More Cultural Than Theological

It is tempting to imagine the relationship between evolution and religion as a battle that began with Darwin and has never ended. But the truth is more complex—and more hopeful.

When Darwin first published On the Origin of Species, the reactions were mixed, even among religious leaders. Some condemned the book outright, while others saw no conflict. Asa Gray, a devout Christian and a prominent American botanist, defended Darwin’s theory and argued that evolution could be the method through which God creates.

Indeed, many religious traditions have long embraced metaphorical or allegorical interpretations of their creation stories. The ancient Hebrew texts, for example, were not written as scientific treatises but as theological poetry—expressions of meaning, not mechanisms.

The idea that science and religion must be at war gained traction in the 19th and 20th centuries, fueled by cultural shifts, political battles, and misunderstandings on both sides. In the United States, the Scopes “Monkey Trial” of 1925 dramatized the divide, pitting evolutionary science against Biblical literalism in a sensational courtroom showdown.

But this framing—science versus religion, reason versus faith—is not universal. It reflects particular historical and cultural contexts, especially in the West. Around the world, many religious communities have found ways to integrate evolution into their worldviews without abandoning their faith.

Different Paths to Truth

One of the key insights that helps reconcile evolution and religion is the idea that they are addressing different kinds of questions. Science seeks to explain the how—the mechanisms behind natural phenomena. Religion often seeks to explore the why—the meaning, purpose, and moral framework within which we live.

As the evolutionary biologist Stephen Jay Gould once proposed, science and religion can be seen as “non-overlapping magisteria”: separate domains of authority that do not need to conflict. Science teaches us how stars form and how species evolve; religion guides our values, our sense of justice, and our relationship to the sacred.

This distinction does not mean that science and religion never interact. They do. And sometimes those interactions are fraught. But recognizing that they are not trying to answer the same questions can create space for dialogue instead of confrontation.

In this view, evolution does not destroy religious belief—it deepens it. It reveals a universe that is dynamic, creative, and unfolding. It shows us a world where life adapts, survives, and diversifies in extraordinary ways. For many religious people, this is not evidence of randomness or godlessness—it is a reflection of divine ingenuity.

The Beauty of an Evolving Creation

Far from diminishing wonder, evolution can inspire it. Consider the sheer grandeur of life’s story: from single-celled organisms in ancient oceans to the emergence of consciousness, art, and love. This is not a tale of purposeless molecules bumping in the void. It is a story of transformation, of resilience, of life finding a way.

For religious thinkers who embrace evolution, this narrative does not negate the Creator—it celebrates the Creator’s method. Instead of fashioning every creature separately, God sets the universe in motion with the capacity for growth and change. Life becomes a symphony of unfolding potential.

Theologians like Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, a Jesuit priest and paleontologist, saw evolution as the very process by which the universe moves toward spiritual fulfillment. He envisioned a cosmos in which science and faith were not in conflict but in harmony—a world in which evolution is the unfolding of divine intention.

Of course, not all religious traditions frame things in the same way. There is a vast spectrum of beliefs, from strict literalism to metaphorical interpretations. But the possibility of coexistence is real and meaningful for those willing to look beyond caricatures.

Evolutionary Morality and Human Uniqueness

Another common concern is that evolution undermines morality. If we are descended from animals, some ask, why should we be moral? If natural selection rewards survival, doesn’t that justify selfishness?

But this fear misunderstands both evolution and ethics. Evolutionary theory does not dictate what we ought to do; it describes what is. It tells us how behaviors may have evolved, not how we should behave. In fact, many moral instincts—such as empathy, cooperation, and fairness—have evolutionary roots. Social animals, including humans, thrive when they care for others.

Religion, meanwhile, provides moral frameworks that transcend biology. It speaks to justice, compassion, and the sacredness of life. These moral visions can be informed by evolution without being reduced to it.

Human uniqueness is not erased by evolution—it is explained. Our capacity for language, culture, ethics, and spirituality has evolved, but it remains extraordinary. Evolution shows us how we are connected to all life, and religion reminds us of our responsibility to that life.

The Danger of Literalism and the Promise of Interpretation

Where conflict most often arises is when religious texts are interpreted rigidly—as literal scientific accounts rather than symbolic stories of meaning. Young Earth creationism, which insists that the Earth is only a few thousand years old and that all species were created separately, directly contradicts vast amounts of scientific evidence.

But this is not the only way to read sacred texts. Many theologians argue that Genesis, for example, is not a textbook but a myth in the true sense of the word—a story that conveys deep truth through metaphor. The seven days of creation need not refer to literal 24-hour periods. Adam and Eve may represent the human condition, not historical individuals.

Such interpretations are not new. Even early Church Fathers like Augustine warned against reading Genesis too literally, cautioning that doing so could make religion look foolish in the face of emerging knowledge.

Interpretation requires humility, imagination, and a willingness to listen—both to ancient voices and to modern discoveries. It is a bridge, not a battle.

Faith in the Age of Science

We live in a time when scientific knowledge is expanding at an unprecedented rate. We can edit genes, peer into black holes, and sequence ancient DNA. These advances can be exhilarating—or disorienting. In such a world, what role can religion play?

For many, religion remains a vital source of meaning. It offers community, moral guidance, and a sense of connection to something greater. Science can tell us how a heart beats, but religion can help us ask why it loves. Science reveals the age of the universe, but religion invites us to wonder what our place in it means.

The danger lies not in science or religion themselves, but in absolutism—when either claims to have all the answers, to be the only way to truth. When science is used to erase wonder, or when religion is used to deny facts, we all lose.

But when both are approached with openness and awe, they can enrich each other. Science can deepen religious understanding, and religion can humanize scientific pursuit. Together, they can help us live wisely and well.

Conclusion: A Shared Journey Toward Truth

Can evolution and religion coexist? The answer, like evolution itself, is complex and evolving. There is no single resolution, no tidy formula that will satisfy every heart or every doctrine. But the evidence of history, theology, and human experience suggests that they can—and do—coexist.

They coexist in the hearts of scientists who see their work as a form of worship. They coexist in classrooms where biology is taught with respect for students’ beliefs. They coexist in churches that celebrate creation’s majesty while accepting its dynamic nature.

Above all, they coexist in the minds of those who refuse to choose between knowledge and faith, between the microscope and the mystery. They recognize that truth is not a territory to be conquered, but a horizon to be explored.

In the end, perhaps the question is not whether evolution and religion can coexist—but whether we are willing to make room in ourselves for both. For wonder and reason. For evidence and meaning. For a world that is not either/or, but richly, beautifully both.