When most people think of human ancestors, a few familiar names echo through time—Lucy, the famous Australopithecus; Homo erectus, the globe-trotter; the robust Neanderthal, long misunderstood as brutish and dumb. These names have become icons of human evolution, etched into the popular imagination like fossils in stone. But beneath the surface of the public story, buried under layers of ancient sediment and scientific caution, lies a world of forgotten relatives—our mysterious, often nameless kin whose bones whisper of strange experiments in walking, eating, surviving, and thinking.

These ancestors didn’t leave behind cave paintings or stone monuments. They didn’t invent fire or tools—or if they did, we haven’t found the evidence. They left us only fragments: a jaw here, a tooth there, the curve of a pelvis, the spiral of a femur. Yet those remnants speak volumes to the trained eye. Each fossil adds another brushstroke to the great canvas of human origin, and together, they reveal a picture far richer, more tangled, and more awe-inspiring than we ever imagined.

In this deep journey through time, we’ll step beyond the spotlight and into the dim corridors of prehistory, exploring the shadowy figures who shaped us long before we were us. From creatures who walked upright millions of years before Homo sapiens evolved, to ghost lineages whose DNA lingers in our cells but whose faces remain unknown—we are about to meet the forgotten ancestors of humanity.

The Rift Where It All Began

Africa, particularly the eastern Rift Valley, is often called the cradle of humanity. This vast geological fault line, stretching thousands of kilometers from the Red Sea to Mozambique, has lifted and exposed ancient rock beds, making it a treasure trove for paleoanthropologists. Yet even with decades of digging, we are still only scratching the surface of our evolutionary past.

Far older than Lucy or any other Australopithecus, some hominins pushed the human line closer to its divergence from chimpanzees—our closest living relatives. It’s estimated that humans and chimps split from a common ancestor somewhere between six and seven million years ago. What came next was not a single straight line, but an explosion of forms—some walking upright, others swinging from trees, all adapting in unique ways to climates and ecologies that fluctuated wildly across millennia.

It is in this complex theater that the lesser-known players emerged—fossils so ancient that their very existence challenges the way we tell our origin story.

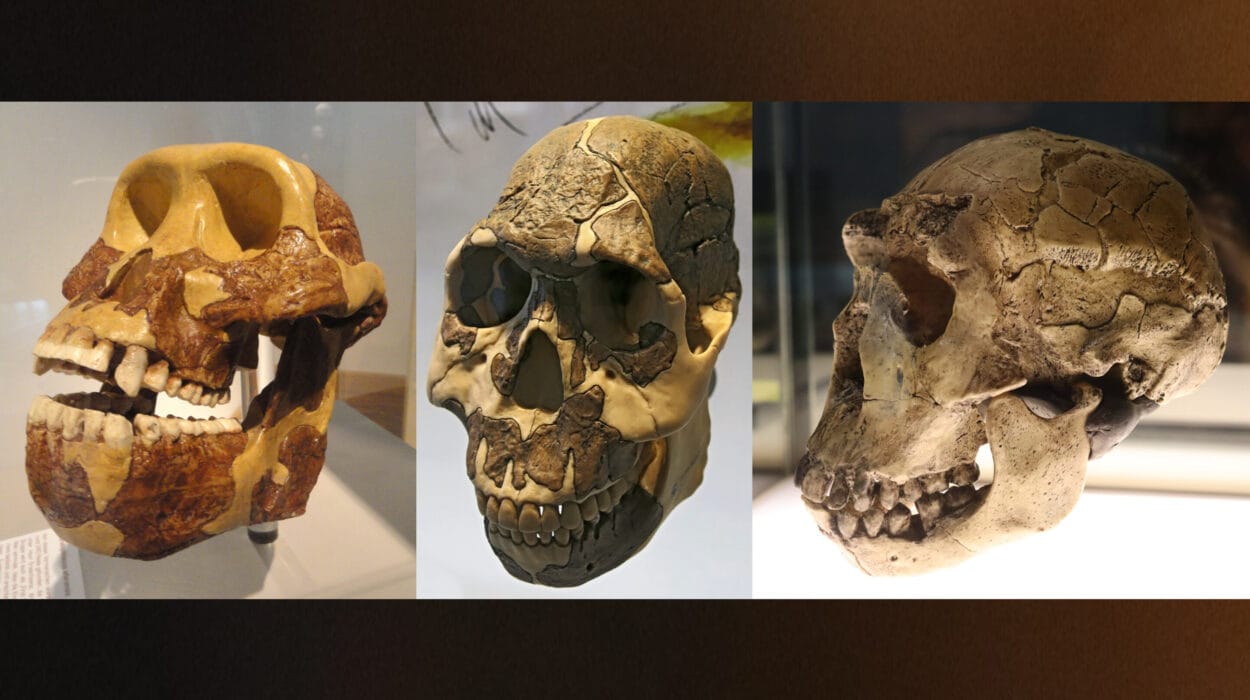

Sahelanthropus tchadensis: The Skull That Changed the Map

In 2001, in the Djurab Desert of Chad, a French and Chadian team led by Michel Brunet discovered a fossil skull that would ignite both excitement and controversy. The skull, known as Toumaï (“hope of life” in the local Daza language), was unlike anything previously found. It had a small braincase, about 360 cubic centimeters—similar to that of a chimpanzee—but with a surprisingly humanlike face: flat, with thick brow ridges and relatively small canines.

But what truly shocked the world wasn’t just its anatomy—it was its age. At nearly seven million years old, Sahelanthropus tchadensis pushed back the earliest evidence of hominins by at least a million years. And it wasn’t found in East Africa, but in central Africa—forcing scientists to reconsider assumptions about where early human ancestors evolved.

What made Sahelanthropus a candidate for the hominin club was the position of the foramen magnum—the hole where the spinal cord enters the skull. Its placement suggested upright walking, though some argue this interpretation is uncertain without postcranial bones. And therein lies the controversy: with only a skull and few fragments, many aspects of its lifestyle remain speculative. Some scholars even suggest it may be closer to apes than humans. Still, Sahelanthropus remains a tantalizing glimpse into the twilight zone of our ancestry.

Orrorin tugenensis: Millennium Man and the Birth of Bipedalism

Discovered just a few years before Sahelanthropus, Orrorin tugenensis emerged from the Tugen Hills of Kenya in 2000. Its name, “Orrorin,” means “original man” in a local language, and its estimated age—6 million years—places it among the oldest potential hominins.

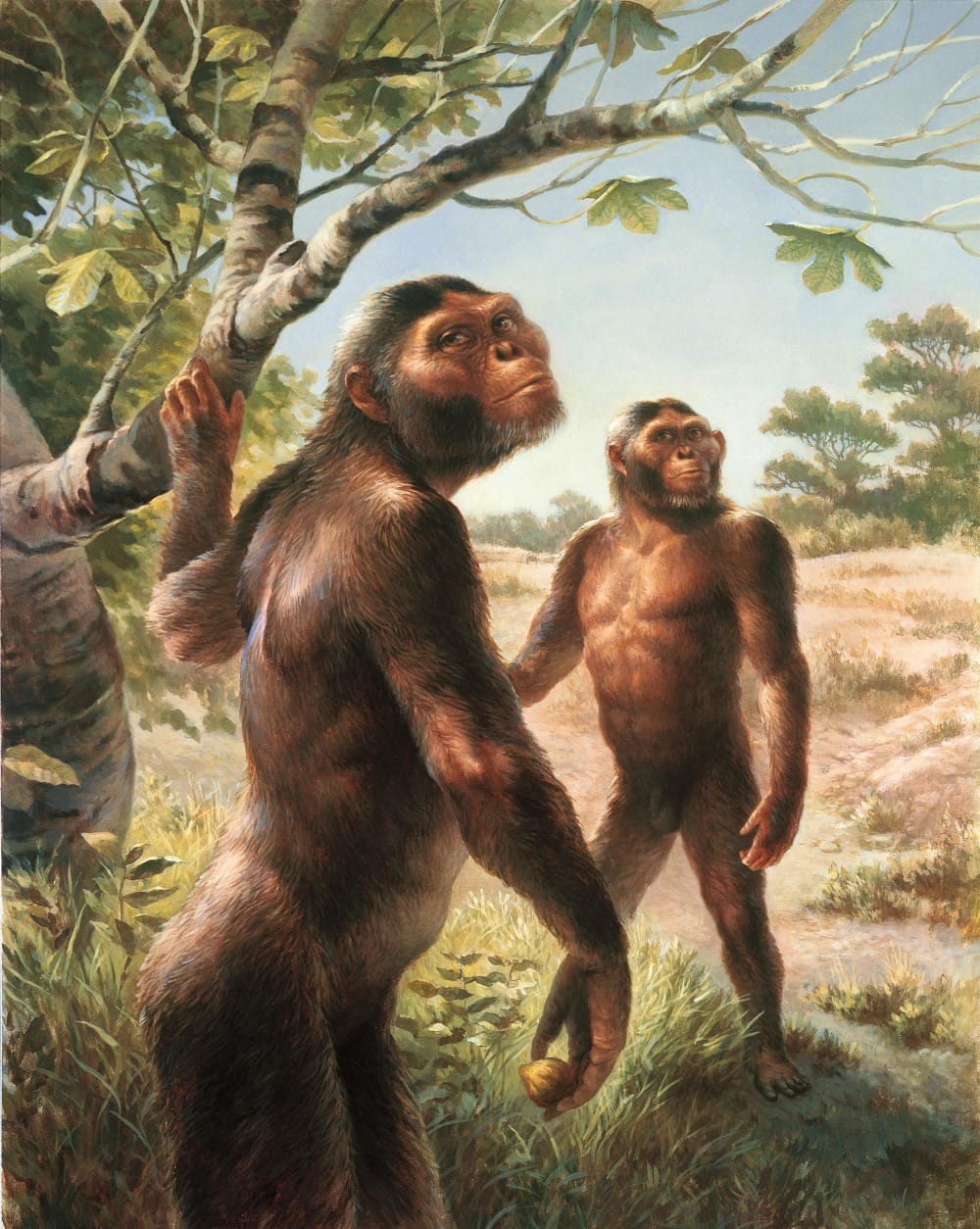

What makes Orrorin remarkable is not its skull (which has not been found), but its femur. The structure of this thigh bone suggests bipedal locomotion. The femoral neck was elongated and the cortical bone thickened in a way that closely resembles later hominins. Yet Orrorin’s arms and curved finger bones suggest it still spent significant time climbing trees.

This duality—part walker, part climber—raises fascinating questions. Was upright walking initially a way to move efficiently between patches of forest? Did it evolve as a response to climate change or to free the hands for carrying food or infants? Orrorin lived in a mixed habitat of forest and grassland, supporting the idea that human evolution didn’t begin in open savannahs, but in environments where both arboreal and terrestrial lifestyles had advantages.

Despite its importance, Orrorin remains lesser known, partly because its remains are fragmentary and its placement on the family tree is debated. But whether a direct ancestor or a side branch, it shows that the road to upright walking began far earlier than once thought.

Ardipithecus ramidus: The Woodland Walker

If Sahelanthropus and Orrorin represent whispers from the dawn of humanity, Ardipithecus ramidus—nicknamed “Ardi”—is a clearer voice. Discovered in Ethiopia in the early 1990s but not fully described until 2009, Ardi lived 4.4 million years ago. The most complete Ardipithecus skeleton reveals a creature both familiar and alien.

She was about 120 centimeters tall and weighed around 50 kilograms. Her pelvis suggested a form of upright walking, but her foot retained a grasping big toe, indicating that climbing remained crucial. Her hands were not built for knuckle-walking, as in chimps and gorillas, suggesting that the common ancestor of humans and apes was not a knuckle-walker either—a revolutionary insight.

What made Ardi especially groundbreaking was her environment. She lived in a woodland setting, not a savannah. This blew a hole in the classic “savannah hypothesis,” which claimed that upright walking evolved as a response to life on open grasslands. Instead, it seemed bipedalism may have begun in trees, as an adaptation that gradually spread to the ground.

Ardi’s anatomy pointed to a more generalized ancestor—neither chimp-like nor fully human. She complicated the picture of our origins and showed that early hominins were not simply scaled-down versions of us, but unique creatures in their own right.

Kenyanthropus platyops: The Flat-Faced Puzzle

In 1999, in Kenya’s Lake Turkana region, Meave Leakey’s team uncovered a skull with a strikingly flat face. Unlike the projecting jaws of australopithecines, this face resembled the flatter profiles of later hominins like Homo rudolfensis. Dated to 3.5 million years ago, it came from roughly the same period as Lucy but looked nothing like her.

Dubbed Kenyanthropus platyops, or “flat-faced man of Kenya,” the fossil presented a major puzzle. Did this represent a separate lineage of early human ancestors? Or was it a variant of Australopithecus? Some researchers argue the fossil is too distorted to interpret clearly; others insist it shows real morphological differences.

If Kenyanthropus was indeed a distinct genus, it means multiple lineages of early hominins with different facial structures and brain sizes coexisted in Africa—an evolutionary bush rather than a ladder. And if it contributed to the genus Homo, it could change how we understand the rise of our own lineage.

Australopithecus deyiremeda: A Neighbor of Lucy

In 2011, Ethiopian paleoanthropologist Yohannes Haile-Selassie and his team discovered fossils just 35 kilometers from where Lucy had been found decades earlier. But these remains, dated to around 3.5 to 3.3 million years ago, were different. Their jaws and teeth didn’t match Australopithecus afarensis. They had thicker enamel and a differently shaped lower jaw.

Named Australopithecus deyiremeda—“close relative” in the Afar language—this species suggested that Lucy had company. It provided yet more evidence that multiple hominin species coexisted in the same regions, perhaps even competing or interacting with each other.

The idea that human ancestors evolved in such diversity adds richness to the narrative, but it also makes it harder to determine which line led to us. Did deyiremeda evolve into Homo? Was Lucy’s species a dead end? Or did both contribute genes to later hominins? The answers remain buried beneath the volcanic ash of East Africa.

The Ghosts in Our DNA

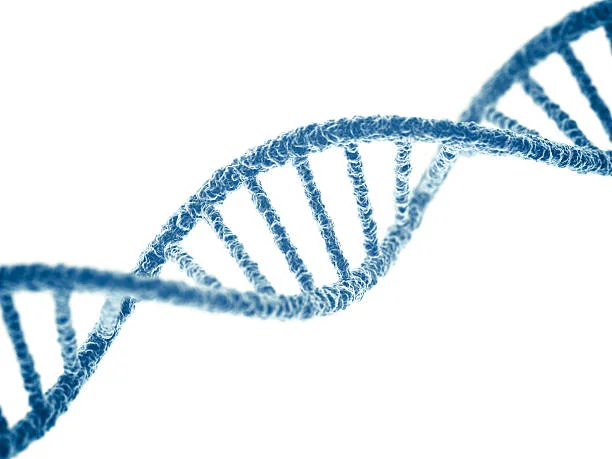

Not all of our ancestors left behind bones. Some left behind genes—silent, enduring traces of past minglings. In recent years, advances in ancient DNA have uncovered surprising relatives known only from genetic evidence. The most famous of these are the Denisovans, identified in 2010 from a single finger bone found in a Siberian cave.

Denisovans were closely related to Neanderthals and interbred with both them and early Homo sapiens. Their DNA lives on in modern Melanesian, Aboriginal Australian, and Southeast Asian populations, sometimes comprising up to 5% of their genomes.

But there are deeper ghosts too. Genetic studies suggest there were at least two or three other archaic human species that bred with our ancestors but left no known fossils. One, nicknamed “Ghost Archaic,” is believed to have contributed DNA to West African populations. These unknown ancestors are invisible in the fossil record but live on in the double helix of our cells.

The implications are profound. Our species did not evolve in splendid isolation. We are not a pinnacle, but a mosaic—a swirling blend of ancient encounters, brief unions, and enduring legacies.

The Incomplete Puzzle

Despite more than a century of fossil hunting, the story of human evolution remains incomplete. For every well-known ancestor like Homo habilis or Homo erectus, there are dozens of lesser-known species that walked beside them—or before them—whose roles are still uncertain. The timeline is messy, the relationships murky. New discoveries often raise more questions than answers.

But that’s the beauty of science. Every fossil is not just a piece of the past—it’s a key to reimagining the future of understanding. And each time a bone is lifted from the earth, it adds another voice to the chorus of who we are.

Conclusion: We Are the Storytellers

The forgotten ancestors of humanity may never be household names. They didn’t leave myths or monuments, and many remain nameless or lost. But without them, we would not exist. They were the dreamers of survival, the wanderers who took a chance on upright walking, the climbers who peeked over the next ridge, the early mothers and fathers of invention, all experimenting with life in ways that eventually led to us.

To know them is not just an act of science, but an act of gratitude. For in their bones, we find echoes of our own fragility and resilience. And in their eyes—though we can only imagine them—we see a flicker of that unmistakable human spark: curiosity, adaptability, and the will to endure.