Before fire was mastered, before wheels turned, before words were written down in stone or ink, there were questions—questions whispered under starlit skies, carved into bones, painted on cave walls. Of all those questions, perhaps none was more haunting, more intimate, than this: Where do we come from?

For centuries, cultures around the world spun myths to answer it. Some said we were shaped from clay by gods. Others believed we were descended from stars or animals or dreams. But today, science tells a different story—a story no less wondrous, no less mysterious. This is the story of our origins, of the ancient paths that led to modern humans. It is not a straight line, nor a simple ladder. It is a tangled tree, a trail of footprints left in deep time, across continents, through extinctions, and into consciousness.

To ask where humans really come from is to embark on one of the greatest journeys ever told—not just of bones and genes, but of identity and meaning.

The Deep Past: More Than Just Apes

The story of human origins does not begin with humans. It begins long before we had names or tools or even ancestors that resembled us. We are mammals, first and foremost. Our story shares a root with all other mammals, a journey that began over 200 million years ago in the shadows of the dinosaurs.

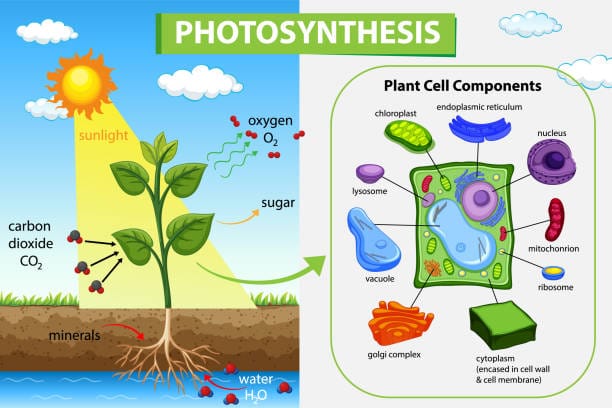

After the great extinction that wiped out the non-avian dinosaurs 66 million years ago, mammals had room to grow, evolve, and diversify. Among them, a group of tree-dwelling primates slowly began to develop traits that would one day prove essential to humans—grasping hands, forward-facing eyes, large brains. These traits were shaped by life in the trees, where depth perception and coordination mattered more than brute strength.

Around 6 to 7 million years ago, in what is now Africa, a crucial branch split from the shared ancestor of chimpanzees and humans. We did not descend from modern apes; rather, we share common ancestors with them. Evolution doesn’t move in straight lines—it branches and twists. That early hominin, perhaps Sahelanthropus tchadensis, walked on two legs, at least part of the time, and possessed a brain slightly larger than that of a chimpanzee. In that split was the first glimpse of what would one day become us.

Walking Upright: The First Footsteps Toward Humanity

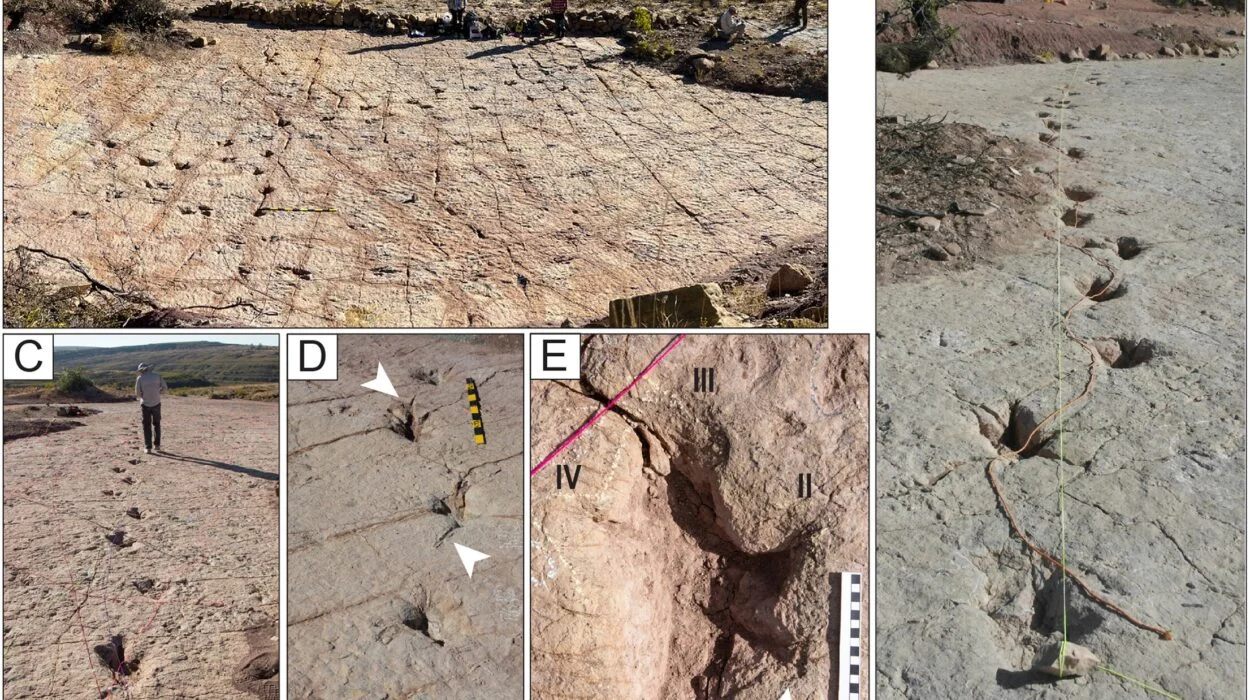

Bipedalism—walking on two legs—was one of the earliest and most defining traits of our lineage. It was not about intelligence or fire, but about posture. The fossil record shows that by 4 million years ago, hominins such as Australopithecus afarensis were regularly walking upright. “Lucy,” the famous 3.2-million-year-old fossil discovered in Ethiopia, stands as one of our earliest walking relatives.

Walking upright changed everything. It freed the hands for other tasks—carrying, throwing, eventually crafting. It also meant a different view of the world, a new way of interacting with the environment, and a new balance between speed and endurance. We weren’t the fastest runners, but we could walk for hours under the hot sun without collapsing. Evolution, in its quiet genius, was building a creature unlike any before it.

Yet for millions of years, those early hominins still had small brains. They lived in small groups, used simple tools, and likely had basic communication. Their lives were still tethered to the animal kingdom, governed more by instinct than by reflection.

The Rise of the Genus Homo

Around 2.5 million years ago, a major transition occurred. The first members of our genus, Homo, began to appear. Homo habilis, often called “handy man,” was among the earliest. Fossils from East Africa suggest these early humans used stone tools—not just sharp rocks, but deliberately shaped tools for cutting, smashing, and scraping. These tools were the first signs of culture.

From Homo habilis emerged Homo erectus, a species that would become one of the most successful hominins in history. With a larger brain and more sophisticated tools, Homo erectus walked out of Africa nearly 2 million years ago and spread into Asia and Europe. Their fossils have been found as far afield as Indonesia and Georgia, showing that our ancestors were explorers long before Homo sapiens existed.

But what caused this leap? Climate likely played a role. Africa’s changing environments forced adaptability. Those who could think ahead, who could remember where waterholes were or use tools to access food, survived. Over generations, brains grew larger. Social cooperation increased. Fire was mastered. Our ancestors were not just reacting to nature—they were beginning to shape it.

Enter Homo sapiens: A New Kind of Mind

The modern human species, Homo sapiens, first appeared around 300,000 years ago in Africa. Fossils from Jebel Irhoud in Morocco show high foreheads, small faces, and other features recognizable in the mirror today. But bones alone do not capture what made Homo sapiens different.

What truly set us apart was our mind. Not just intelligence, but imagination. We were capable of abstract thought, symbolic language, planning, and empathy. Around 100,000 years ago, evidence of art, burial rituals, and long-distance trade began to appear. Shell beads, ochre patterns, carved figures—these were signs of a mind reaching beyond the here and now.

This was the birth of culture. Not just habits passed down, but meaning shared through stories, symbols, and collective memory. Our ancestors were no longer just surviving—they were wondering, questioning, dreaming.

The Great Migrations and the Meeting of Species

Around 70,000 years ago, a small group of Homo sapiens began leaving Africa, following coastlines and rivers, encountering new landscapes—and other humans. For by then, we were not alone.

In Europe lived the Neanderthals, Homo neanderthalensis, a robust species with their own tools, burials, and possible language. In Asia lived the Denisovans, known mostly from genetic evidence and a few fossil fragments. In Indonesia, tiny hominins like Homo floresiensis shared the forest. The world was once populated by many kinds of humans.

But we did not simply replace them—we met them, and we mingled. Genetic studies show that most people today carry traces of Neanderthal and Denisovan DNA. These were not brutal conquests, but complex encounters—alliances, exchanges, perhaps even love. Slowly, however, the other human species disappeared. Climate, competition, and absorption into larger Homo sapiens populations likely played a role.

By 30,000 years ago, we were the last humans standing.

The Agricultural Revolution: A Double-Edged Inheritance

For tens of thousands of years, Homo sapiens lived as hunter-gatherers—nomadic, egalitarian, deeply connected to the land. But around 10,000 years ago, something shifted. In regions like the Fertile Crescent, China, and Mesoamerica, humans began to domesticate plants and animals. The Agricultural Revolution was not an overnight change but a gradual turning point.

Farming allowed for surplus food, which allowed for larger communities, which led to cities, governments, writing, and civilizations. It enabled the pyramids, the Parthenon, the Great Wall—but also war, hierarchy, and disease.

Agriculture brought abundance, but also inequality. Land could now be owned. Power could be hoarded. Diets narrowed, and life expectancy sometimes declined. Yet this transformation also unleashed culture on a massive scale—religions, philosophies, sciences. We became not just clever animals but world-builders, capable of shaping landscapes and future generations.

The Genetic Map: What DNA Tells Us About Our Roots

Today, our understanding of human origins is sharpened by the lens of genetics. The Human Genome Project and advances in ancient DNA have turned bones and stones into living stories. By comparing genomes across modern populations and ancient remains, scientists have traced migration patterns, admixture events, and evolutionary changes.

Mitochondrial DNA, inherited from mothers, points to a common female ancestor—sometimes called “Mitochondrial Eve”—who lived in Africa around 150,000 to 200,000 years ago. This does not mean she was the only woman alive, but that her lineage is the one that survived unbroken to the present.

Similarly, Y-chromosome studies trace paternal ancestry to a common male ancestor, “Y-chromosomal Adam.” These ancestral lines are part of a complex tapestry of genes, not isolated stories but interwoven paths.

We now know that all living humans share over 99.9% of their DNA. Race, once seen as a biological reality, is now understood as a social construct with no meaningful genetic basis. Beneath skin and language and culture, we are astonishingly alike.

Culture, Consciousness, and the Story of Us

What truly makes us human is not just biology but culture. Language allowed us to teach, to plan, to dream across generations. Art allowed us to feel and remember. Religion gave us meaning in the face of death. Science gave us tools to understand the stars and the atoms.

Our species, Homo sapiens, means “wise human.” But our wisdom is not guaranteed. We are a young species, still learning the consequences of our power. We split the atom before we understood its dangers. We altered the climate before we accepted our role in it.

Yet, we are also the species that painted the ceilings of caves 30,000 years ago, that walked on the Moon, that mapped our own DNA, that sends messages into space hoping someone else is out there. We are not just survivors—we are storytellers.

So Where Do We Really Come From?

We come from Africa, from the soil of savannas and the roots of ancient trees. We come from upright walkers, from fire keepers, from toolmakers and storytellers. We come from mothers and fathers who endured ice ages, droughts, and migrations. We come from clans and tribes, from poets and warriors.

We come from others, too—from Neanderthals, Denisovans, and forgotten cousins whose names we may never know but whose blood still sings in our veins.

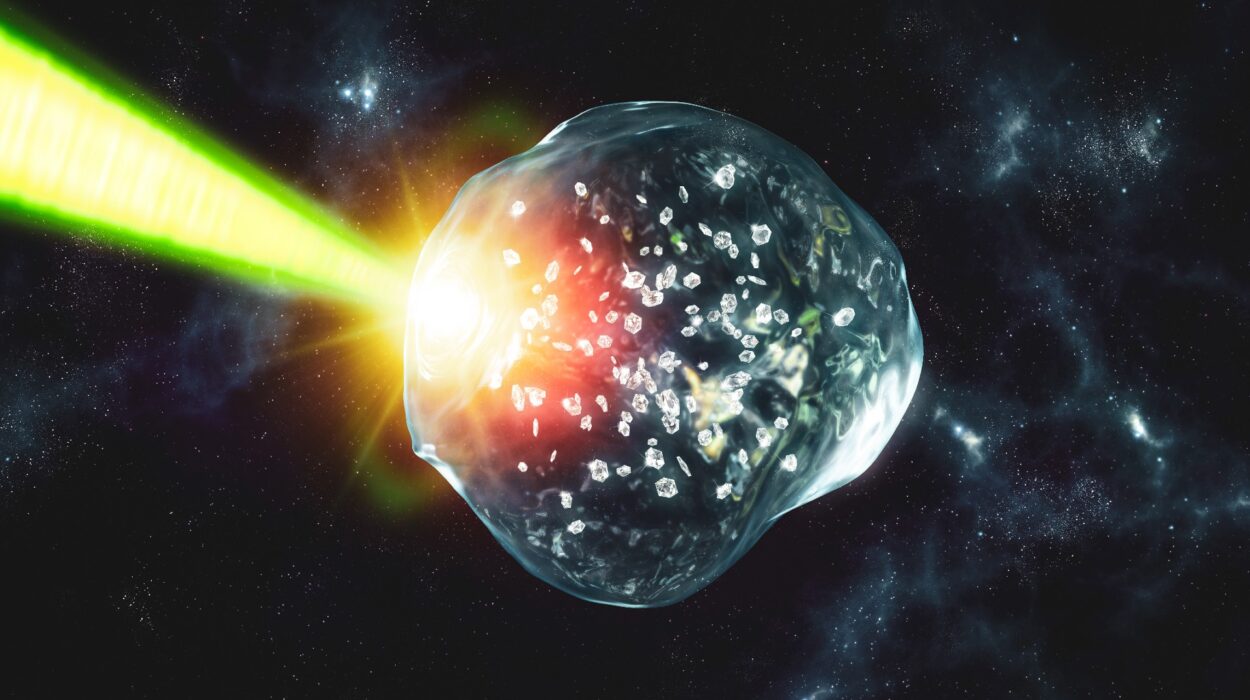

And we come from stardust, ultimately—from the elements forged in dying stars, scattered across galaxies, gathered by gravity into planets and life and, finally, us.

Our story is not finished. Each child born carries the full history of life within them—every mutation, every migration, every memory. And they will carry our story forward, into futures we cannot yet imagine.

To ask where humans really come from is to ask not just about the past, but about our place in the vast unfolding of existence. We come from Earth, yes. But also from the wonder, from the questions, from the awe.

We are not just the product of evolution. We are evolution becoming conscious of itself.