Winter in Colorado is not just a season. It is a test. Snow deepens, temperatures plunge, and the familiar colors of the landscape drain away into white and gray. For wildlife, this is not merely uncomfortable; it is a moment when survival depends on ancient strategies shaped over hundreds of thousands of years. Some animals sleep through it. Others grow thicker coats, hide away food, or leave entirely. But a small, remarkable group responds to winter by becoming someone else, at least in appearance.

As the days shorten and snow begins to settle, a handful of Colorado animals fade into the landscape itself. Browns and grays dissolve into white. Bodies become harder to see, harder to catch, harder to notice. It is one of nature’s quietest transformations, happening without fanfare, often without witnesses, and it remains one of the least understood adaptations in the wild.

The Rarity of Becoming Snow

Only 21 species worldwide are known to change color seasonally from darker summer coats or plumage to winter white. Almost all of them live in northern climates. In Colorado, just four species carry this genetic legacy: snowshoe hares, white-tailed ptarmigan, short-tailed weasels, and long-tailed weasels, the latter two often grouped together under the name ermine.

“It’s kind of a rare adaptation,” said Hannah Rumble, the Community Programs Director for the Walking Mountains Science Center, an Eagle County nonprofit focused on nature education. “So, it’s really uncommon.”

That rarity is part of what makes these animals so compelling. They are living evidence of an evolutionary gamble that paid off, at least for a very long time. Each fall, without fail, their bodies respond to the approaching winter not by waiting for snow to fall, but by reading the sky itself.

Listening to the Light

The trigger for this transformation is not cold, and not snow, but light. As winter approaches and daylight hours shrink, something inside these animals responds. Scientists call this change in daylight a photoperiod, and it appears to set off the molting process that replaces summer fur or feathers with winter white.

Why some cold-weather animals evolved this response while others did not is still unclear. Rumble explained that the reasons behind the color change are probably twofold. The most obvious benefit is camouflage. A white coat in winter can mean the difference between disappearing into the snow or standing out like a signal flare to predators or prey.

But there is another advantage hidden beneath the surface. When these animals molt in the fall, their new fur or feathers grow back without melanin, the pigment that gives color. Without it, the hair becomes hollow. Air fills the empty space, and that trapped air provides extra insulation against the cold. The white is not just disguise. It is warmth.

When Disappearing Is the Difference Between Life and Death

For animals like ermine, camouflage works in two directions. The white coat helps them hide from predators, but it also allows them to slip unseen toward their prey. For others, like snowshoe hares, blending into the snow can mean escaping the sharp eyes of hunters that roam the winter landscape.

Yet not every animal in snowy environments uses this strategy. Bridget O’Rourke, a public information officer for Colorado Parks & Wildlife, pointed out that pikas rely on rock piles to defend themselves from predation. Black-tailed jackrabbits, relatives of the snowshoe hare, live in prairie or semi-desert environments where snow is far less common, so changing color would offer little advantage.

Adaptation is never about what could be useful everywhere. It is about what works exactly where you are.

The Modern Problem of Being Too Perfect

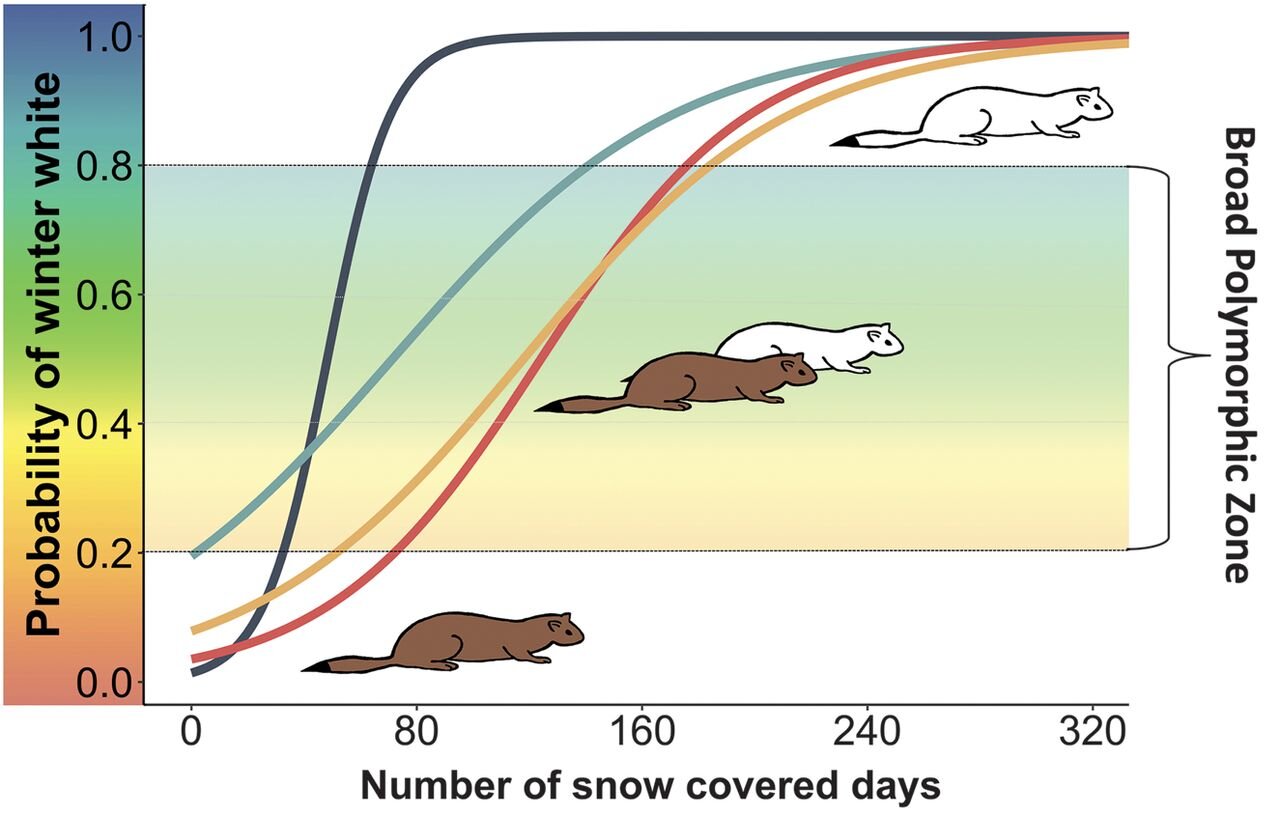

For generations, turning white in winter was a nearly flawless strategy. Snow reliably covered the ground. White meant invisible. But today, that reliability is breaking down.

As the climate warms, snow arrives later, melts earlier, or sometimes barely comes at all. The animals still change color, because the trigger is daylight, not temperature. The result can be devastating. A white animal against brown earth or patchy snow becomes painfully visible.

This situation has a name: phenotypic mismatch. It happens when the environment changes faster than a plant or animal can adapt to it.

“There is a lot of concern for alpine species,” Rumble said.

The transformation that once offered protection can suddenly become a liability, exposing animals at the very moment they need concealment most.

A Flash of White on the Mountainside

For those lucky enough to witness them, Colorado’s color-shifting animals offer fleeting moments of wonder.

Ermine, both long-tailed and short-tailed weasels, are brown in summer and “a brilliant white” in winter, aside from their black-tipped tails, according to Colorado Parks & Wildlife. Long-tailed weasels are fairly common on public lands across the state, while short-tailed weasels tend to stick to forested mountain areas.

Skiers sometimes glimpse them from chairlifts at Vail and other resorts, or in places like Rocky Mountain National Park. But Rumble said the best way to look for them in winter is on snowshoe or cross-country ski trails during the day.

“They are more active, especially in the winter, to stay warm,” she explained. At night, they retreat to their dens.

Walking Mountains Science Center offers free snowshoe nature walks and backcountry hikes at its Eagle County locations, including one at the top of the Eagle Bahn Gondola at Vail Mountain, though the gondola ride itself comes at a cost. On those walks, Rumble has seen both species of weasel.

One encounter still stands out. On the nonprofit’s Sweetwater Campus, she once watched a long-tailed weasel carrying away a cottontail rabbit it had hunted and killed.

“It was amazing to witness because there are not a lot of predators that go after something larger than them. A rabbit is three to five times heavier than a weasel,” she said.

The Tracks That Tell a Story

Snowshoe hares are much harder to spot directly, especially when their white coats blend seamlessly into the snow. But they leave behind unmistakable evidence.

Their tracks, pressed into fresh powder, are almost comical in their size. The oversized hind feet that give the hare its name act like natural snowshoes, keeping the animal buoyant in deep snow.

“Compared to a cottontail rabbit, their legs are huge… a lot bigger than you might expect,” Rumble said.

Her advice is simple: look for the tracks first. Once you find them, follow their path with binoculars, letting your eyes move slowly along the trail until the shape of the hare reveals itself.

Snowshoe hares live across most of Colorado’s mountains, except for the southeastern Front Range around Pikes Peak and the Sangre de Cristo mountains. Like ermine, they are more often seen during the day in winter, making snowshoe and cross-country ski trails ideal places to look.

Ghosts of the High Alpine

If spotting a snowshoe hare requires patience, finding a white-tailed ptarmigan demands something closer to devotion.

Ptarmigan live above 9,500 feet in elevation, blending so completely into rocky slopes during summer that they seem to vanish into the terrain. In winter, they turn white, matching the snow with equal perfection. But winter access to their high alpine tundra habitat is extremely limited.

“Alpine species stay there year-round, but most of us can’t get that high in winter.”

Members of the grouse family, ptarmigan are about the size of a pigeon. Before winter closes in, sharp-eyed observers with binoculars may find them near high-alpine lakes in the backcountry, along Trail Ridge Road in Rocky Mountain National Park, above timberline on peaks like Mount Blue Sky and Pikes Peak, or from high passes like Loveland Pass.

Trail Ridge Road and Mount Blue Sky close in winter, but Loveland Pass and Pikes Peak remain open. Even then, Rumble emphasized that spotting a ptarmigan takes a great deal of patience and luck.

Sometimes, you can be looking directly at one and still not see it.

Why This Story Matters Now

The animals that turn white in winter are more than seasonal curiosities. They are living indicators of how finely tuned life can be to its environment, and how fragile that tuning becomes when conditions shift.

Their transformations tell a story of evolutionary success written over immense spans of time. At the same time, their growing vulnerability tells a story about the speed of modern change. When snow becomes unreliable, invisibility becomes exposure. When camouflage fails, survival hangs in the balance.

Understanding these animals matters because they remind us that adaptation is not infinite. It has limits. And when those limits are reached, the consequences ripple outward through ecosystems.

To notice a flash of white on a winter trail, or a set of oversized tracks crossing fresh snow, is to glimpse both the beauty of evolution and the urgency of the present moment. These animals have learned to read the light of shortening days. Now, the challenge lies with us, to read what their struggle is telling us about the world we share.