Far beneath the surface of the Mediterranean Sea, where sunlight fades into darkness and silence presses in from all sides, a vast scientific instrument waits patiently. Suspended in the deep, the KM3NeT neutrino telescope network listens not for sound, but for something far stranger — the faint traces of neutrinos, elusive subatomic particles often called “ghost particles.”

These particles barely interact with matter. They stream through planets, stars, and even our own bodies almost without a trace. Most pass unnoticed. But once in a while, one collides with something, leaving behind a brief and brilliant signature.

Recently, the KM3NeT collaboration recorded something extraordinary. A single high-energy neutrino event carrying an astonishing 220 PeV (peta-electron volts) of energy. To scientists, that number is breathtaking. It marks one of the most energetic neutrino detections ever observed.

And it posed an urgent question: Where did it come from?

A Signal That Shouldn’t Be Ignored

When news of the event spread, astrophysicists around the world leaned in. High-energy neutrinos are rare and fleeting. They do not announce themselves twice. If one appears, it carries a story from the far reaches of the cosmos.

The origin of this particular event, however, was unclear. Its cosmological origin had not yet been identified. There was no obvious culprit, no neatly labeled cosmic explosion pointing back to its source.

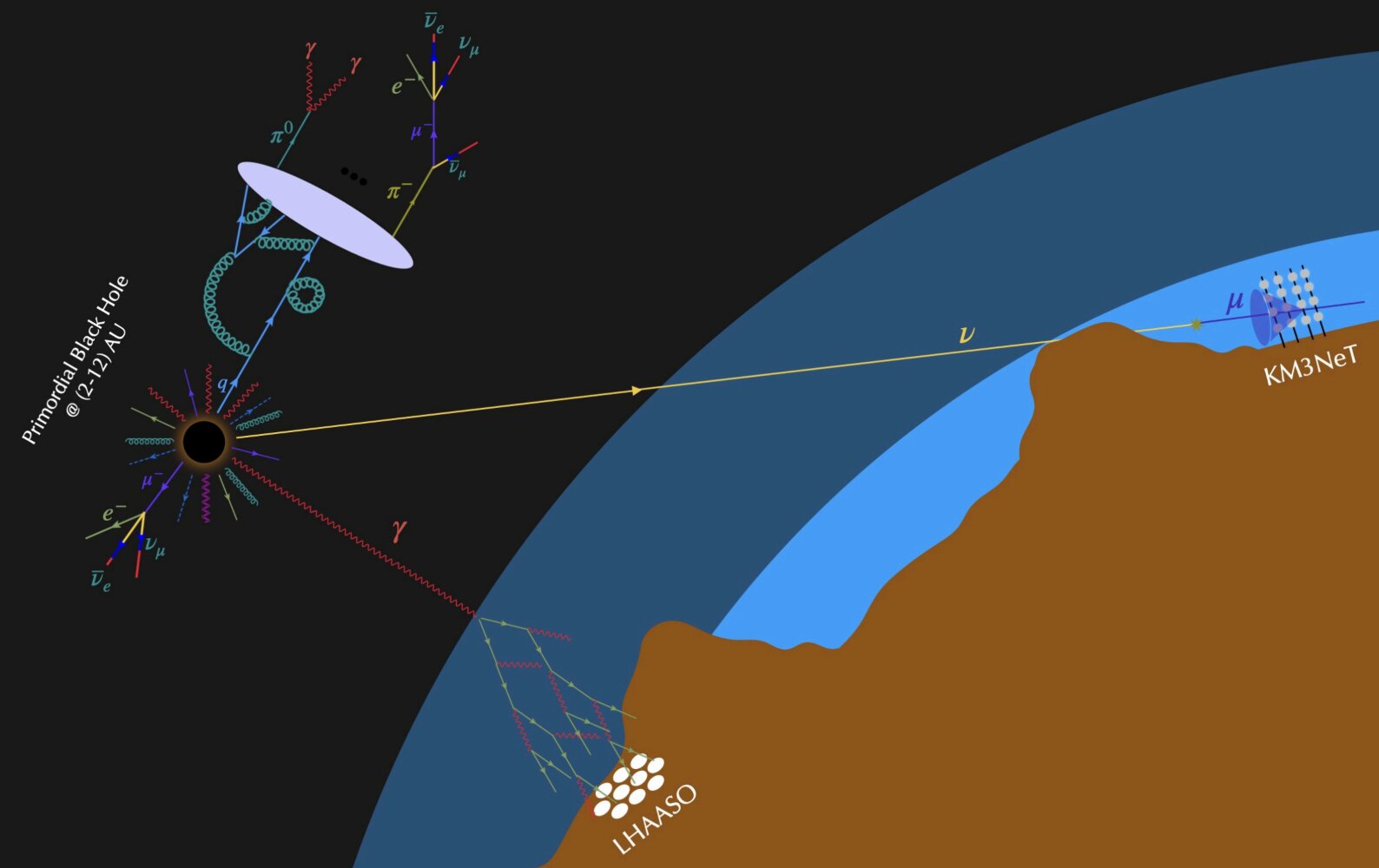

Among the ideas that began circulating was a dramatic possibility: what if the neutrino had come from the final moments of a primordial black hole — a tiny black hole formed shortly after the Big Bang — exploding somewhere near Earth?

It was a bold suggestion. If true, it would mean that a black hole had ended its life practically in our cosmic backyard.

The Final Breath of a Tiny Black Hole

At the Universidade de São Paulo and the Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, researchers were already thinking about short-lived cosmic events when the KM3NeT discovery was announced. Led in part by Yuber F. Perez-Gonzalez, the team had been studying how neutrino and gamma-ray telescopes respond to bursts lasting less than an hour.

Short cosmic flashes are tricky. Timing and direction matter enormously. Neutrinos traveling toward Earth may pass through different amounts of the planet before reaching a detector. The more Earth they cross, the less likely they are to be observed. A brief event in one part of the sky might be detectable, while the same event elsewhere might vanish unnoticed.

The team had been focusing on a specific scenario: the final evaporation of a primordial black hole. According to theory, as such a black hole shrinks, it should release a burst of high-energy particles in its last moments.

If a primordial black hole had indeed evaporated near Earth, it could, in principle, produce a neutrino with the immense energy observed by KM3NeT.

But that would not be all.

A Cosmic Explosion That Wouldn’t Stay Quiet

A black hole’s final evaporation would not whisper. It would shout.

Perez-Gonzalez and his colleagues set out to calculate how close such a primordial black hole would need to be to produce a 220 PeV neutrino detectable by KM3NeT. Then they asked an even more crucial question: what else would we see?

Because an evaporating primordial black hole would not emit neutrinos alone. It would also release a storm of gamma rays and cosmic rays — high-energy electromagnetic radiation and fast-moving particles racing through space.

Such an event should leave fingerprints across multiple observatories, not just in a deep-sea neutrino detector.

The team carefully modeled realistic detector sensitivities and actual observing conditions. They did not rely on simplified assumptions. They examined when different observatories were looking at the relevant region of the sky and whether they would have been capable of seeing the predicted signals.

One facility stood out in particular: the Large High Altitude Air Shower Observatory (LHAASO) in Tibet, a major gamma-ray detector designed to capture precisely these kinds of energetic bursts.

If a primordial black hole had exploded close enough to produce the KM3NeT neutrino, LHAASO should have recorded a very large gamma-ray signal — and it should have done so several hours before the neutrino event.

But no such signal was seen.

The Case Against a Nearby Black Hole

The absence of that gamma-ray burst was decisive.

In their paper, published in Physical Review Letters, the researchers concluded that the primordial black hole explanation is highly implausible. A nearby black hole evaporation powerful enough to produce the detected neutrino would have left unmistakable traces elsewhere.

And those traces simply were not there.

The dramatic idea of a tiny black hole exploding near Earth, at least in this case, appears to fade under careful scrutiny.

The neutrino, then, must have come from somewhere else.

Why Timing Changes Everything

Beyond ruling out one spectacular possibility, the study delivered an important methodological lesson.

Perez-Gonzalez emphasized that very short neutrino events must be analyzed with explicit attention to the time-dependent fields of view of different detectors. It is not enough to average sensitivities over long periods. Transient events unfold in real time, and detectors are not always looking everywhere.

Using time-averaged assumptions can lead to misleading conclusions. A detector might be capable of seeing a signal in theory, but only if it was actually pointed in the right direction at the right moment.

By accounting for when observatories were actively monitoring specific regions of the sky, the researchers strengthened their argument. The missing gamma-ray signal was not a matter of bad luck or blind spots. LHAASO should have seen it — and did not.

That absence speaks loudly.

A Mystery That Remains

The KM3NeT event still stands as one of the most energetic neutrino detections ever recorded. Its source remains unknown.

If not a primordial black hole, then what?

The researchers do not claim to have solved the mystery. Instead, they have narrowed the field. Future studies can build on this framework to explore other astrophysical explanations.

The universe is filled with violent, energetic phenomena. Somewhere among them lies the true origin of the 220 PeV neutrino.

For now, the story remains unfinished.

Why This Matters More Than One Particle

It may seem astonishing that so much effort can be devoted to a single subatomic particle. But events like this are rare windows into extreme cosmic environments.

Neutrinos travel vast distances almost untouched. They carry pristine information from places that light alone may not fully reveal. Each high-energy detection is a messenger from the universe’s most powerful processes.

The rejected black hole hypothesis, though unlikely in this case, remains scientifically important. Observing the evaporation of a primordial black hole would provide direct evidence for Hawking radiation, a fundamental prediction of modern physics. Confirming it would reshape our understanding of black holes and quantum theory.

Even without that dramatic outcome, this study highlights something essential about modern astrophysics: discoveries do not stand alone. They are tested against networks of instruments, cross-checked across wavelengths and particle types, and examined under realistic observing conditions.

By combining data from neutrino detectors like KM3NeT and gamma-ray observatories such as LHAASO, scientists are building a more complete picture of the high-energy universe. Each observatory is a different sense organ, and only together can they interpret fleeting cosmic events.

The deep-sea detector caught a whisper from the cosmos. The silence from Tibet answered back. Between those signals — and that silence — scientists are slowly piecing together the truth.

The mystery of the 220 PeV neutrino endures. But thanks to careful theoretical work, one extraordinary possibility has been tested and found wanting. And in science, ruling something out is not a disappointment. It is progress.

Somewhere in the vastness beyond Earth, an extreme astrophysical engine hurled a ghostly particle across unimaginable distances. It reached a detector in the dark Mediterranean depths. And because of that single flash of energy, we now understand a little more about what did not happen — and a little better how to search for what did.

The universe keeps sending its messages. We are learning how to read them more carefully than ever before.

Study Details

Lua F. T. Airoldi et al, Could a Primordial Black Hole Explosion Explain the Extremely High-Energy KM3NeT Neutrino Event?, Physical Review Letters (2026). DOI: 10.1103/w9dp-dfkx.