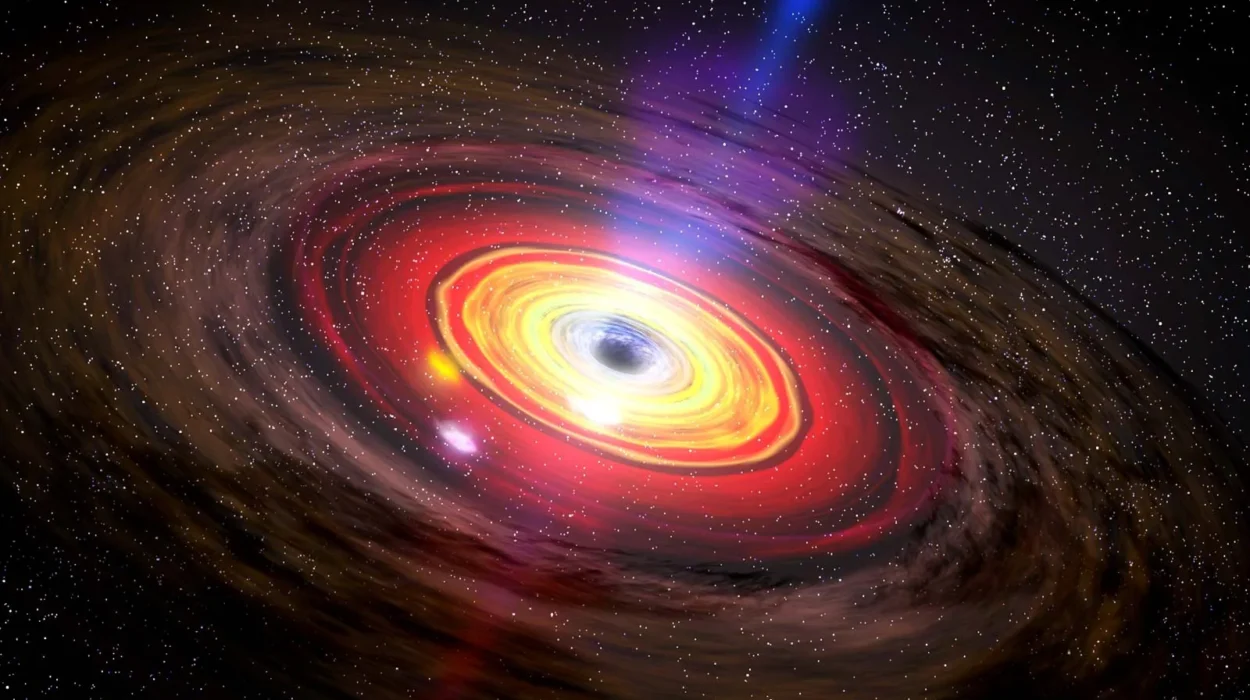

The James Webb Space Telescope has once again turned its unblinking eye toward the cosmos and found something that seems almost impossible. Deep in the glow of a star only slightly smaller and cooler than our sun, a rocky world named TOI-561 b circles so close that its entire orbit fits within a single Earth day. Less than one million miles from its star, its surface is a permanent ocean of molten rock. And yet, despite this inferno, Webb has revealed the strongest evidence so far that this superheated world carries something no one expected a planet like this to keep. An atmosphere.

For years, scientists assumed small rocky planets this close to their stars must be stripped bare, their gases blasted away by relentless radiation. But TOI-561 b refuses to behave. Instead, it wears what researchers describe as a thick blanket of gases above its global magma ocean, a shroud that should not be there and yet appears unmistakably in the light Webb collected.

Its discovery does more than expand our catalog of strange worlds. It shakes the very assumptions about how planets hold themselves together under extreme conditions and offers a glimpse into what planets may have looked like when the universe was young.

A Planet That Should Not Exist

TOI-561 b belongs to a rare family known as ultra-short period exoplanets. With a radius 1.4 times that of Earth and an orbit shorter than 11 hours, it resides in a region so near its star that the dayside temperature far exceeds the melting point of ordinary rock. The planet is most likely tidally locked, meaning one face always bakes in eternal daylight, while the other peers forever into darkness.

This alone would make it an object worth studying. But researchers noticed something even stranger. Its density is far lower than expected for a world of its size. That oddity set off a chain of questions.

Lead author Johanna Teske from Carnegie Science explained the puzzle with crisp clarity. “What really sets this planet apart is its anomalously low density. It is less dense than you would expect if it had an Earth-like composition.” She and her team explored whether TOI-561 b might simply be built differently from Earth. Perhaps it has a smaller iron core or a mantle made of lighter rock.

But the planet’s environment also offered a crucial clue. “TOI-561 b is distinct among ultra-short period planets in that it orbits a very old, iron-poor star—twice as old as our sun—in a region of the Milky Way known as the thick disk. It must have formed in a very different chemical environment from planets in our own solar system.”

This unusual birthplace suggested the planet’s composition might reflect conditions from a younger universe. But composition alone could not fully explain the observations. Something else had to be at work.

A Suspicion Takes Shape

One possibility kept resurfacing. What if TOI-561 b wasn’t simply low-density rock? What if the planet looked larger than it actually is because it was wrapped in a thick atmosphere?

The idea went against everything researchers typically expect from small planets that endure billions of years of fierce radiation. Yet hints from other rocky worlds suggested that the rules might not be so rigid. Some of these scorched exoplanets show signs of tenuous atmospheres clinging on at the edges of destruction.

Dr. Anjali Piette from the University of Birmingham painted a vivid portrait of the forces at work. “We really need a thick, volatile-rich atmosphere to explain all the observations. Strong winds would cool the dayside by transporting heat over to the nightside.

“Gases like water vapor would absorb some wavelengths of near-infrared light emitted by the surface before they make it all the way up through the atmosphere. The planet would look colder because the telescope detects less light, but it’s also possible that there are bright silicate clouds that cool the atmosphere by reflecting starlight.”

These possibilities were provocative—but unproven. To settle the question, the team turned to Webb.

Watching the Glow of a Burning World

Using Webb’s NIRSpec instrument, the researchers measured the planet’s dayside temperature not by touching the world itself but by watching a subtle dimming. When TOI-561 b slipped behind its star, the system’s overall brightness dipped just enough for the team to detect the missing glow.

If the planet were a bare ball of molten rock with no atmosphere to move heat around, its dayside should blaze at nearly 4,900 degrees Fahrenheit (2,700 degrees Celsius). But that is not what Webb saw. Instead, the dayside temperature appeared closer to 3,200 degrees Fahrenheit (1,800 degrees Celsius). In cosmic terms, this difference is enormous. Something was cooling the planet, and the cooling was far too strong to be explained by exposed rock alone.

The researchers explored every scenario they could. A magma ocean could move some heat, but without an atmosphere, the nightside would eventually freeze solid and block heat circulation. A thin layer of rock vapor rising from the molten surface might dim the glow slightly, but nowhere near enough to match the observations.

The evidence pointed again and again to the same conclusion. A substantial atmosphere must be present.

A Planet in a Perpetual Exchange

But if TOI-561 b truly has such an atmosphere, how does it keep it?

This world sits in a beam of radiation intense enough to strip away gas faster than most planets could replenish it. And yet the atmosphere persists. Co-author Tim Lichtenberg from the University of Groningen offered a compelling explanation. “We think there is an equilibrium between the magma ocean and the atmosphere. While gases are coming out of the planet to feed the atmosphere, the magma ocean is sucking them back into the interior. This planet must be much, much more volatile-rich than Earth to explain the observations. It’s really like a wet lava ball.”

A wet lava ball. It is an image that feels almost mythical, a world defined by fire but sustained by vapor, endlessly trading material between sky and sea. The planet exists not in balance but in ceaseless exchange, its atmosphere fed by the molten depths while those same depths swallow it back.

Such a cycle might allow a planet like TOI-561 b to cling to an atmosphere for billions of years despite the violence of its environment.

The Long Watch and What Comes Next

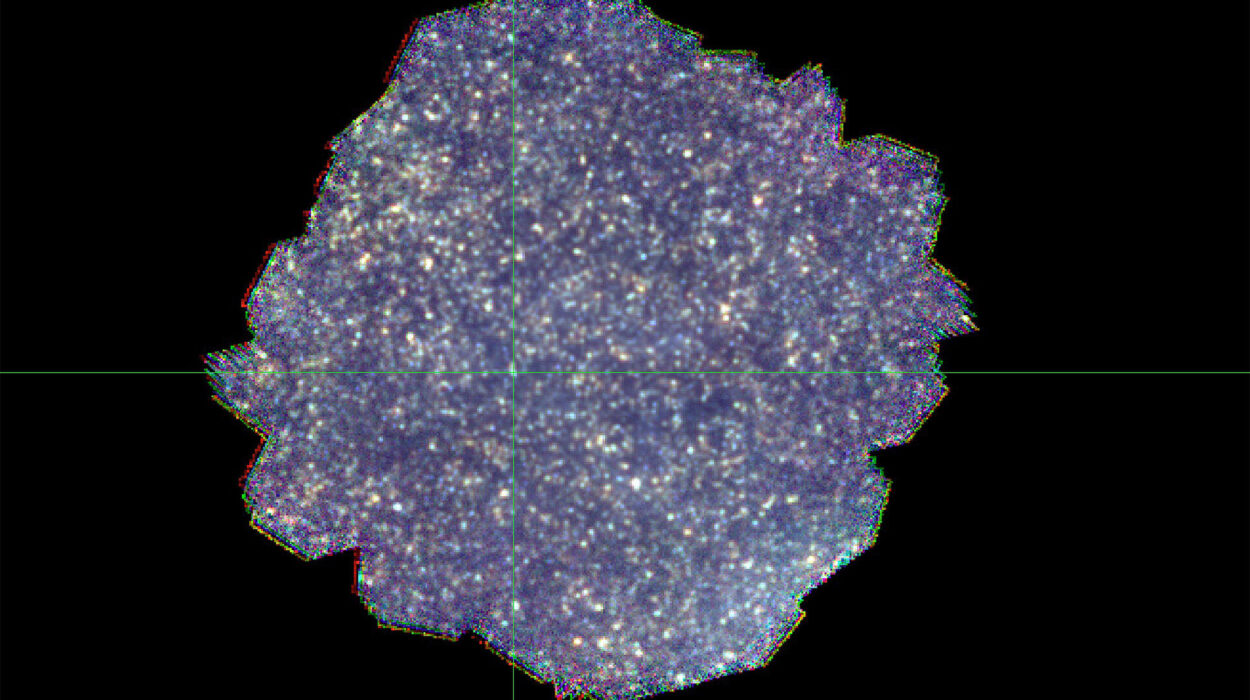

These results mark only the beginning. They come from the first observations of Webb’s General Observers Program 3860. The telescope stared at the system continuously for more than 37 hours, long enough for TOI-561 b to complete nearly four entire orbits. And yet the data still holds deeper secrets.

The team is now analyzing the full set of measurements to map temperature across every part of the planet and identify the specific gases swirling in its atmosphere. Each step brings them closer to understanding not only this one extraordinary world but the possibilities for rocky planets across the galaxy.

Why This Discovery Matters

The discovery of a thick atmosphere on TOI-561 b is more than an astronomical curiosity. It challenges the long-standing belief that extreme proximity to a star inevitably strips small planets bare. It suggests that volatile-rich worlds may be more resilient than expected. It shows that rocky planets formed in ancient, chemically different environments may develop in ways unlike anything seen in our own solar system.

Most importantly, it reveals that the universe still holds surprises even in the places we assumed were most predictable. A world of molten oceans and winds of vapor, orbiting an ancient star in the quiet thick disk of the Milky Way, now forces scientists to rethink how planets live, die, and evolve.

TOI-561 b is a reminder that the cosmos is richer, stranger, and more inventive than we imagine. And thanks to Webb, that story is only beginning.

More information: Johanna K. Teske et al, A Thick Volatile Atmosphere on the Ultra-Hot Super-Earth TOI-561 b, The Astrophysical Journal Letters (2025). iopscience.iop.org/article/10. … 847/2041-8213/ae0a4c . On arXiv: DOI: 10.48550/arxiv.2509.17231