For years, the data sat quietly in digital storage, untouched, unassuming, and holding a secret no one had yet noticed. Then, in a moment that felt almost cinematic, Northwestern University astronomers uncovered something extraordinary hiding in that old telescope footage. It was a planet unlike any they had ever seen, a world that orbits not one star but two, glowing in the light of twin suns like the fictional landscapes of Tatooine. But this was no fantasy. This was a real exoplanet, directly imaged and scientifically confirmed, and it happened to be the closest-in such planet ever spotted around a binary star.

The surprise, the rarity, the sheer improbability of the discovery gave it a dreamlike quality. It was the kind of scientific twist that feels destined for a movie screen, yet it unfolded through careful, methodical work with years-old observations.

And it all started with a strange, faint speck of light refusing to behave like a star passing by.

The Planet That Should Have Been Impossible to See

There are more than 6,000 known exoplanets. Only a very small number of them orbit two stars. And from that already tiny group, only a handful have ever been directly imaged. That rarity alone makes this discovery astonishing. But the new planet pushed the boundaries even further, sitting six times closer to its suns than any other directly imaged planet found in a binary system.

“Of the 6,000 exoplanets that we know of, only a very small fraction of them orbit binaries,” said Northwestern’s Jason Wang. “Of those, we only have a direct image of a handful of them, meaning we can have an image of the binary and the planet itself.”

The ability to see both the stars and the planet at once opens a door to something scientists almost never get to do. As Wang explained, “Imaging both the planet and the binary is interesting because it’s the only type of planetary system where we can trace both the orbit of the binary star and the planet in the sky at the same time. We’re excited to keep watching it in the future as they move, so we can see how the three bodies move across the sky.”

That motion will help researchers test ideas about how planets form in the chaotic gravitational fields of multi-star systems — places where forces twist and pull with complexity far beyond what happens around a single sun.

A Search That Began a Decade Ago

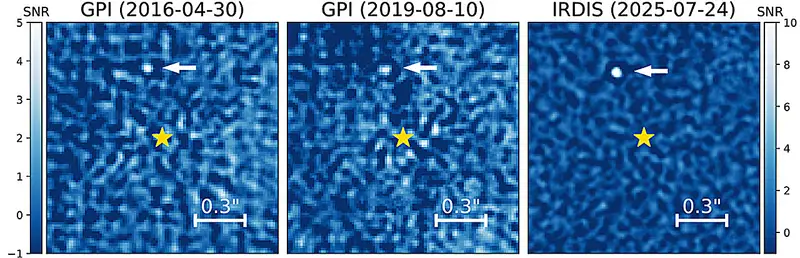

This newly discovered planet did not appear in fresh observations. Instead, it revealed itself only after scientists went back to examine data captured years before, using the Gemini Planet Imager, or GPI. The instrument was originally mounted on the Gemini South telescope in Chile and designed to block out the fierce glare of stars so faint planets could come into view.

“We undertook this big survey, and I traveled to Chile several times,” Wang said. “I spent most of my time during my Ph.D. just looking for planets. During the instrument’s lifetime, we observed more than 500 stars and found only one new planet. It would have been nice to have seen more, but it did tell us something about just how rare exoplanets are.”

Nearly ten years later, as GPI prepares for an upgraded future in Hawaii, Wang decided to close the chapter on the old dataset. He asked graduate researcher Nathalie Jones to take one final, careful look. He wasn’t expecting much.

“I didn’t think we’d find any new planets,” Wang said. “But I thought we should do our due diligence and check carefully anyway.”

The Suspicious Speck That Refused to Drift Away

Jones began sifting through data collected between 2016 and 2019, comparing the observations with those from the W. M. Keck Observatory. Then, quietly but unmistakably, a pattern emerged. A faint object kept following one particular star — not for days or weeks but over years.

“Stars don’t stand still in a galaxy, they move around,” Wang said. That motion makes a clever test possible. If an apparent planet turns out to be a distant star merely passing behind, its movement across the sky will not match the nearby star in the image.

“We look for objects and then revisit them later to see if they have moved elsewhere,” Wang explained. “If a planet is bound to a star, then it will move with the star.”

This one moved with its star.

Jones also examined the object’s light. “We know what light from a star looks like versus what light from a planet looks like,” she said. “We compared them and decided it better matched what we expect to see from a planet.”

It was unmistakable. It was real. And in a scientific twist worthy of parallel discovery, a European team at the University of Exeter — working independently — found the same world in a separate reanalysis, confirming it.

A Giant Born After the Age of Dinosaurs

When the nature of the object became clear, its characteristics only deepened the astonishment. The planet is enormous — six times the size of Jupiter — yet relatively cool compared to other directly imaged exoplanets. It lies about 446 light-years from Earth. Not exactly next door, but, as Wang puts it, “not within our local solar neighborhood but like the next town over.”

Most surprising of all, it is very young. Having formed roughly 13 million years ago, it arrived just 50 million years after the extinction of the dinosaurs — barely an eyeblink on cosmic scales.

“That sounds like a long time ago, but it’s 50 million years after dinosaurs went extinct,” Wang said. “That’s relatively young in universe speak, so it still retains some of the heat from when it formed.”

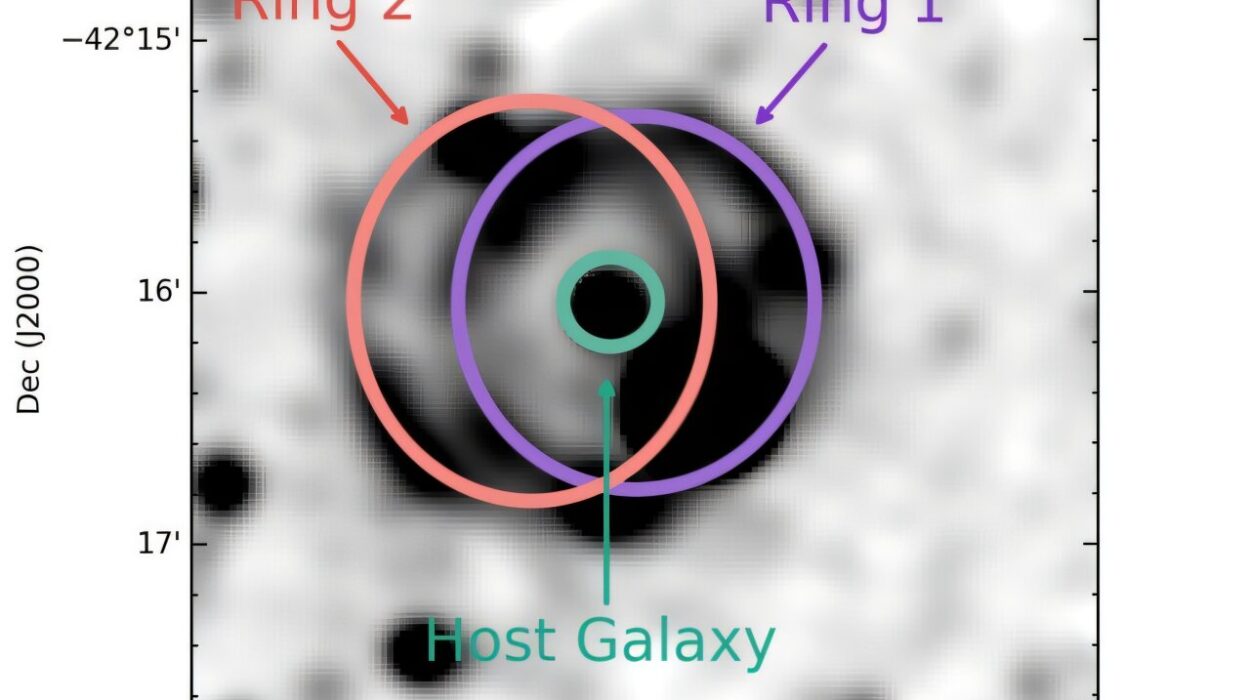

Even the dance of the system is unusual. The two stars orbit each other rapidly, completing a revolution in just 18 Earth days. The planet, by contrast, moves with glacial patience, taking 300 years to encircle the pair.

“You have this really tight binary, where stars are dancing around each other really fast,” Wang said. “Then there is this really slow planet, orbiting around them from far away.”

A Mystery Still Waiting to Be Solved

The planet may orbit far out compared to the stars, but it is still dramatically closer than any other directly imaged planet found in a binary system. How could such a world form in a place where gravitational forces twist and collide with enormous power

“Exactly how it works is still uncertain,” Wang said. “Because we have only detected a few dozen planets like this, we don’t have enough data yet to put the picture together.”

The team’s plan now is simple yet ambitious. They want more time with the telescopes — more chances to watch the system shift, orbit, and reveal deeper clues about its origins. “I’m asking for more telescope time, so we can continue looking at this planet,” Jones said. “We want to track the planet and monitor its orbit, as well as the orbit of the binary stars, so we can learn more about the interactions between binary stars and planets.”

The work also highlights the quiet treasure hidden in old data. “There are a couple suspicious objects,” Jones said, “but what they are, exactly, remains to be seen.”

Why This Discovery Matters

The finding goes far beyond adding one more dot to the catalog of known exoplanets. This one offers scientists a rare laboratory where theory meets reality in a vivid, moving picture across the sky. By tracking how the planet and its two suns orbit together, astronomers can probe deep into the physics of how planets form in environments far more complex than our own single-star system.

Binary stars are common in the universe, but directly watching them with an orbiting planet is almost unheard of. Each new observation gives scientists a better sense of how stable such systems are, how planets survive their chaotic beginnings, and what kinds of worlds might exist around the countless twin suns scattered across the galaxy.

Most of all, this discovery shows that the universe still hides wonders in places we thought we had already searched. Even old, familiar data can whisper new secrets — if someone looks again with fresh eyes.

More information: HD 143811 AB b: A directly imaged planet orbiting a spectroscopic binary in Sco-Cen, The Astrophysical Journal Letters (2025). iopscience.iop.org/article/10. … 847/2041-8213/ae2007

V. Squicciarini et al, GPI+SPHERE detection of a 6.1 MJup circumbinary planet around HD 143811, Astronomy & Astrophysics (2025). DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/202557104