In the autumn of 1604, the night sky performed a quiet miracle. In a familiar constellation that sailors, scholars, and farmers had known for generations, a new star suddenly appeared—brilliant, unmistakable, and impossible to ignore. It shone more brightly than Jupiter, casting shadows at night and demanding attention from anyone who dared to look up. This was not supposed to happen. According to centuries-old beliefs rooted in Aristotelian philosophy, the heavens were perfect and unchanging. New stars did not appear. And yet, there it was.

This stellar explosion, now known as Kepler’s Supernova, was more than a spectacular astronomical event. It was a turning point in human understanding, a cosmic announcement that the universe was far more dynamic, violent, and alive than previously imagined. Observed and carefully documented by Johannes Kepler, one of history’s greatest astronomers, the supernova became a bridge between the old worldview and the birth of modern science. It marked the violent death of a star, but it also marked the rebirth of astronomy itself.

Kepler’s Supernova was the last supernova ever observed in our Milky Way galaxy with the naked eye. Its light faded long ago, but its impact has never dimmed.

A Sky That Was Supposed to Be Eternal

To appreciate the emotional and intellectual shock of Kepler’s Supernova, it is essential to understand the world into which it appeared. In the early seventeenth century, Europe stood at the edge of transformation. The Renaissance had revived learning and curiosity, yet ancient ideas still held tremendous authority. Aristotle’s teachings, reinforced by religious doctrine, described the heavens as immutable. Earth was a realm of change and decay, but the sky beyond the Moon was eternal, flawless, and fixed.

Astronomy existed, but it was constrained by philosophy. The stars were thought to be embedded in crystalline spheres. Planets followed perfect circular paths. Change belonged to Earth alone.

This worldview had already been shaken in 1572, when Tycho Brahe observed a bright new star—now known as Tycho’s Supernova. That event planted doubt, but doubt alone does not overturn centuries of belief. When Kepler’s Supernova appeared in 1604, it struck a universe already trembling with uncertainty.

The sky was no longer behaving as it was supposed to.

The Night the Star Was Born

On October 9, 1604, observers across Europe and Asia noticed an unfamiliar point of light in the constellation Ophiuchus, near the border with Sagittarius and Scorpius. At first, some mistook it for a planet. Others feared it was an omen. Astrology and astronomy were still closely linked, and sudden changes in the sky were often interpreted as signs of impending disaster.

Johannes Kepler saw the star shortly after its appearance. By then, Kepler was already a respected mathematician and astronomer, deeply engaged in unraveling the true nature of planetary motion. Yet even for a mind as bold as his, the sight was astonishing.

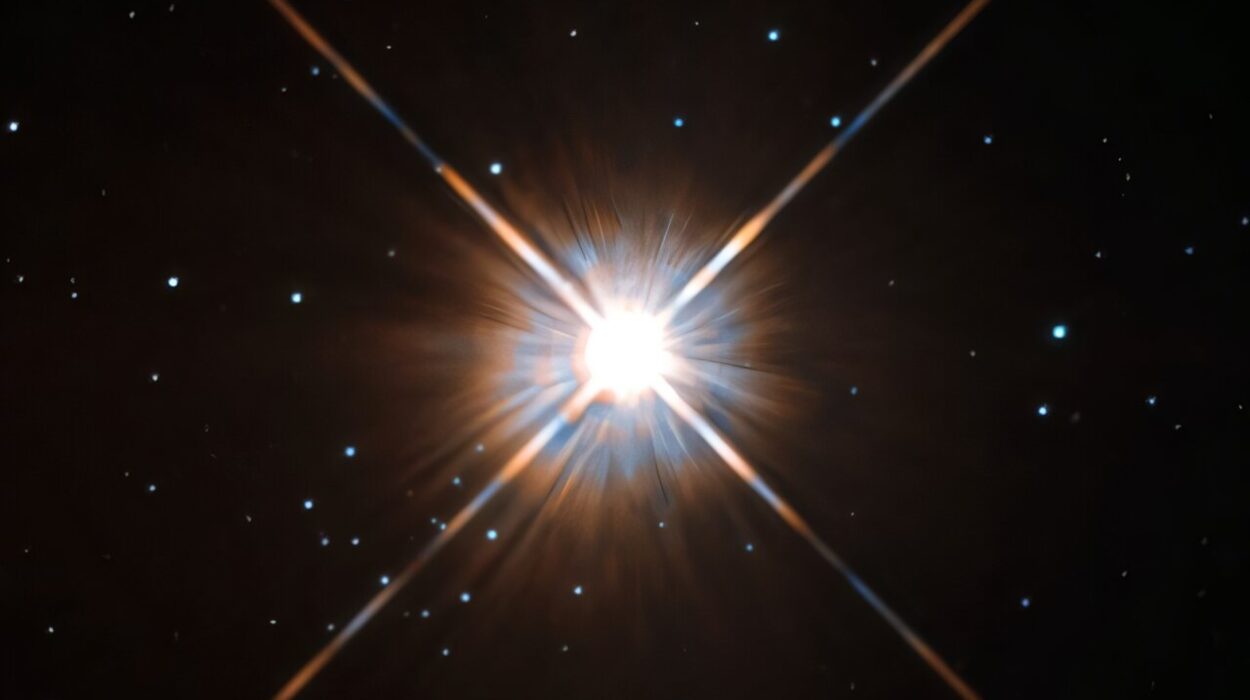

The star brightened rapidly, soon outshining every star in the night sky and rivaling the Moon itself. Unlike a comet, it showed no tail. Unlike a planet, it did not move against the background stars. Night after night, it remained fixed in place, blazing with an intensity that seemed almost supernatural.

This was not a visitor passing through the heavens. This was something new, something born—or dying—in the very fabric of the stars.

Johannes Kepler: A Witness to Cosmic Change

Johannes Kepler was uniquely positioned to interpret what he saw. Trained in mathematics, deeply religious, and passionately curious, Kepler lived at the crossroads of old and new thought. He believed that the universe was designed according to mathematical harmony, reflecting the mind of its creator. Yet he also believed that observation must guide understanding, even when it contradicted tradition.

Kepler observed the new star carefully over many months. He measured its position relative to nearby stars and found no detectable parallax. This meant the object was not close to Earth, like the Moon or planets, but truly distant, among the stars themselves.

This conclusion was devastating to the old cosmology. If the star was located in the supposedly unchanging heavens, then change was happening there too.

Kepler documented his observations in a detailed book published in 1606. In it, he did not merely describe the star’s brightness and position. He grappled with its meaning, wrestling with both scientific implications and philosophical consequences. The heavens, he realized, were not frozen in perfection. They were capable of birth, transformation, and destruction.

A Star That Outshone the World

At its peak, Kepler’s Supernova was extraordinarily bright. Historical records suggest it reached a visual magnitude of about minus three, making it brighter than Jupiter and visible even during daylight hours. For weeks, it dominated the night sky, an unmissable beacon of cosmic violence.

People reacted in different ways. Some felt fear, convinced it foretold war, plague, or the fall of kingdoms. Others felt wonder, sensing that they were witnessing something rare and profound. For astronomers, the supernova was both a gift and a challenge—a chance to learn, but also a demand to rethink everything they thought they knew.

Over time, the star slowly faded. Its brightness declined over many months, changing color as it dimmed, until it eventually vanished from naked-eye view in early 1606. To the casual observer, the event ended there. But to science, it was only the beginning.

What Kepler’s Supernova Really Was

Today, we know that Kepler’s Supernova was the catastrophic explosion of a star, an event so energetic that it briefly rivaled the brightness of an entire galaxy. Specifically, it is classified as a Type Ia supernova, a particular kind of stellar explosion that occurs in a binary star system.

In such systems, a white dwarf star—the dense, Earth-sized remnant of a once Sun-like star—orbits a companion. Over time, the white dwarf pulls matter from its partner. As it gains mass, its internal pressure and temperature rise. When it reaches a critical threshold, nuclear reactions ignite uncontrollably, and the star is torn apart in a thermonuclear explosion.

The entire star is destroyed. No core remains. What is left behind is an expanding shell of superheated gas and newly forged elements racing outward into space at thousands of kilometers per second.

Kepler and his contemporaries could not have known this. Nuclear physics lay centuries in the future. Yet their careful observations laid the groundwork for this understanding. Kepler’s Supernova became a cornerstone in the study of stellar death.

The Supernova Remnant: A Ghost That Still Glows

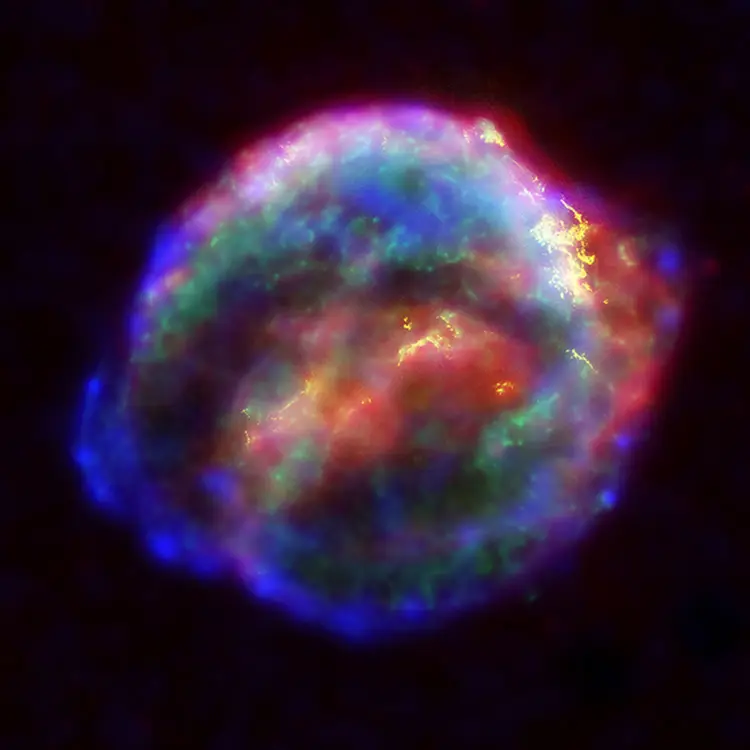

Although the star itself vanished centuries ago, its remains are still visible today. The Kepler Supernova Remnant is a complex, glowing cloud of gas located about 20,000 light-years from Earth. It spans several light-years and continues to expand, carrying the chemical fingerprints of the explosion.

Modern telescopes, observing in radio waves, X-rays, and visible light, reveal a turbulent structure filled with shock waves and glowing filaments. These emissions come from gas heated to millions of degrees as it collides with surrounding interstellar material.

The remnant tells a story written in energy and motion. It confirms that the explosion was asymmetric, shaped by the environment around the star and possibly by the motion of the progenitor system through space. It also provides critical evidence supporting the Type Ia classification.

In this ghostly afterimage, astronomers read the final chapter of a star that died four centuries ago—and the opening chapter of countless future stars yet to be born.

Why Kepler’s Supernova Matters to Modern Science

Kepler’s Supernova holds a special place in astrophysics because Type Ia supernovae are among the most important tools in modern cosmology. These explosions have remarkably consistent intrinsic brightness. By comparing how bright they appear from Earth to how bright they truly are, astronomers can calculate their distances.

This property makes Type Ia supernovae “standard candles,” cosmic measuring sticks that allow scientists to map the scale of the universe. Observations of distant supernovae of this type led to the discovery that the expansion of the universe is accelerating—a finding that reshaped cosmology and introduced the concept of dark energy.

Kepler’s Supernova, as one of the nearest and best-studied historical examples, provides a crucial reference point. By studying its remnant, scientists test models of how these explosions work, improving the accuracy of cosmic distance measurements.

In this way, a star that died in 1604 continues to influence our understanding of the entire universe.

A Blow to Cosmic Perfection

Beyond its scientific value, Kepler’s Supernova played a critical role in the philosophical transformation of astronomy. It was one of several observations that shattered the idea of an unchanging sky. Along with Tycho’s Supernova and Galileo’s telescopic discoveries, it helped dismantle the ancient division between the corruptible Earth and the perfect heavens.

The universe was revealed to be a place of constant activity—stars forming, evolving, and dying; galaxies colliding; space itself stretching and bending. Change was not an imperfection but a fundamental feature of reality.

This realization altered humanity’s relationship with the cosmos. The sky was no longer a static backdrop to human affairs. It became a dynamic arena governed by the same physical laws everywhere.

Kepler’s Inner Struggle and Cosmic Faith

Kepler’s response to the supernova was deeply personal. He did not view the universe as a cold machine. To him, nature reflected divine order and purpose. The sudden appearance of a new star forced him to reconcile faith with evidence.

Rather than rejecting observation, Kepler embraced it. He argued that change in the heavens did not diminish their beauty or meaning. Instead, it revealed a more complex and living creation. In his writings, scientific reasoning and spiritual reflection coexist, showing that the emotional impact of discovery can be as profound as its intellectual consequences.

Kepler’s Supernova thus stands as a symbol of intellectual courage—the willingness to let reality reshape belief.

The Last Naked-Eye Supernova in the Milky Way

Since 1604, no supernova has appeared in our galaxy that is visible to the naked eye. Many have occurred, but dust clouds obscure much of the Milky Way, hiding these events from human eyes. Kepler’s Supernova remains the last time an entire civilization could look up without telescopes and witness the death of a star.

This fact gives the event a quiet poignancy. It connects modern astrophysics with an era when science was still emerging from myth, when a single point of light could unsettle empires of thought.

One day, another supernova will likely blaze in our sky. When it does, it will be studied with instruments Kepler could never have imagined. Yet the emotional experience—the shock, the wonder, the sense of cosmic vulnerability—will be much the same.

A Star That Changed Humanity’s Perspective

Kepler’s Supernova was not just an astronomical event. It was a moment when the universe spoke loudly, forcing humanity to listen. It revealed that stars are not eternal beacons but mortal entities with life cycles. It showed that the cosmos evolves, just as life on Earth does.

In witnessing the death of a star, humans took another step toward understanding their own place in the universe. We are not spectators watching a static sky. We are participants in a dynamic cosmos, born from ancient stellar explosions and destined to be reshaped by cosmic forces beyond our control.

The light of Kepler’s Supernova faded centuries ago, but its legacy burns on—in scientific theory, in philosophical insight, and in the quiet awe that still accompanies every glance at the night sky.