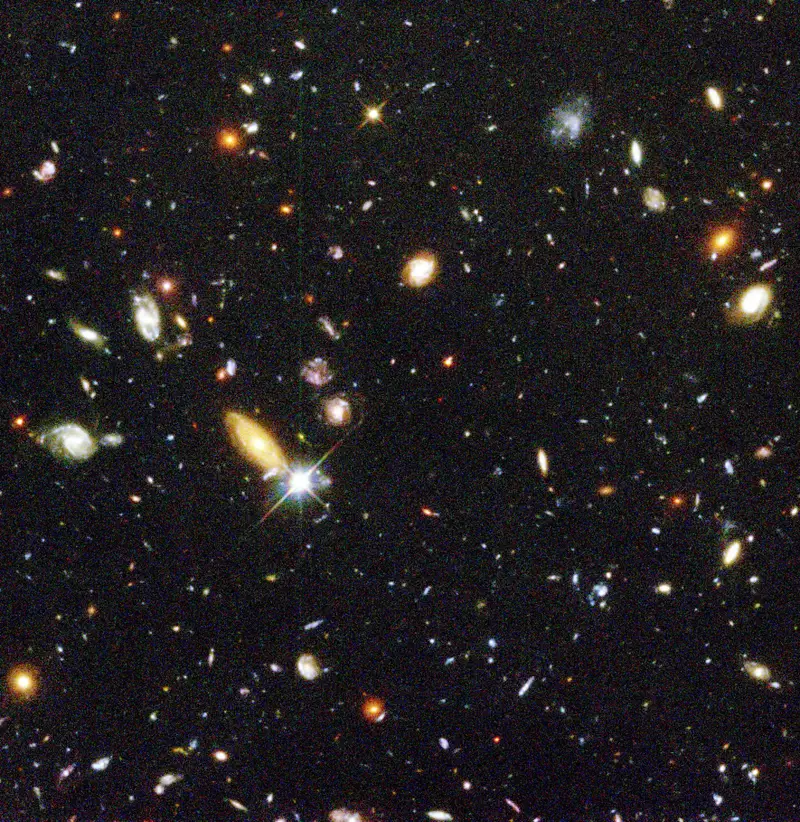

There are moments in human history when a single image quietly rearranges how we understand existence. Not through spectacle or shock, but through patience, humility, and truth. The Hubble Deep Field is one such image. At first glance, it looks unremarkable: a scattered spray of tiny lights against deep blackness. But contained within that darkness is a revelation so vast that it permanently altered humanity’s sense of scale, place, and cosmic belonging.

The Hubble Deep Field is not just a photograph. It is a confrontation with immensity. It is a reminder that the universe is far larger, older, and richer than our instincts ever prepared us to imagine. Before it existed, the cosmos felt enormous but abstract. After it, vastness became intimate, almost personal. One small patch of sky, smaller than a grain of sand held at arm’s length, turned out to contain thousands of entire galaxies. Each galaxy held billions of stars. Many of those stars likely hosted planets. And this realization emerged not from speculation, but from light patiently collected across unimaginable distances and time.

This single image changed astronomy, reshaped cosmology, and quietly unsettled our sense of importance. It forced humanity to recalibrate reality itself.

A Telescope Above the World

To understand why the Hubble Deep Field mattered so profoundly, one must first understand the instrument that made it possible. The Hubble Space Telescope was conceived as a dream long before it became hardware. Astronomers had known for decades that Earth’s atmosphere distorts and absorbs light, blurring distant objects and blocking entire wavelengths from view. The idea of placing a telescope above the atmosphere promised clarity that ground-based observatories could never achieve.

When Hubble finally launched into orbit in 1990, it carried the weight of extraordinary expectations. Those expectations were initially betrayed when the telescope revealed a flaw in its primary mirror, producing blurred images and public embarrassment. Yet this failure became part of the Hubble story rather than its end. Astronauts repaired the telescope during a daring servicing mission, transforming it into one of the most productive scientific instruments ever created.

Once corrected, Hubble delivered images of astonishing sharpness. It revealed star-forming regions in glowing detail, resolved distant galaxies, and measured cosmic expansion with unprecedented precision. But despite its successes, even Hubble was initially used conservatively. Observing time was precious, and astronomers favored targets that promised clear scientific returns. No one pointed it blindly into darkness. At least, not at first.

The Risk of Looking at Nothing

In the mid-1990s, a bold and deeply counterintuitive idea began circulating among astronomers. What if Hubble were aimed at a region of sky that appeared completely empty? Not a nebula, not a galaxy cluster, not anything that looked promising. Just darkness.

From a practical standpoint, the idea was risky. Telescope time was limited, expensive, and fiercely competitive. Dedicating many consecutive days to a blank patch of sky could yield nothing at all. The detectors might collect only noise. Critics worried that the experiment would waste precious resources and embarrass the mission if it failed.

But the proposal rested on a powerful intuition. Astronomers suspected that what appeared empty was an illusion caused by the limits of observation. The universe might be filled with faint, distant galaxies whose light was simply too weak to detect in short exposures. If Hubble stared long enough, perhaps those hidden structures would emerge.

This was not guaranteed. It was an act of scientific faith grounded in theory, curiosity, and courage.

Choosing a Patch of Darkness

The chosen region of sky lay in the constellation Ursa Major. It was deliberately selected to be as unremarkable as possible. The area contained no bright stars, no known galaxies, no obvious features that might contaminate the image. It was, by all appearances, a cosmic void.

The region was tiny. From Earth, it would appear smaller than a grain of sand held at arm’s length. It was the kind of place astronomers usually ignored, scanning past it on their way to more interesting targets.

And yet, Hubble was commanded to stare at this emptiness. For days. Then weeks. Light began accumulating, photon by photon, striking the telescope’s detectors after journeys lasting billions of years. The universe, silent and patient, began to reveal what had always been there.

The Emergence of the Deep Field

When the data were finally processed and the image assembled, the result stunned even the most optimistic astronomers. The so-called empty patch of sky was anything but empty. It was crowded with galaxies, thousands of them, layered at different distances and stages of cosmic history.

Some appeared as graceful spirals, others as fuzzy ellipses, and many as irregular smudges, warped and chaotic. These distorted shapes were not flaws in the image. They were young galaxies caught in the act of formation, collisions, and transformation. The further away a galaxy lay, the earlier in time it appeared. The Hubble Deep Field was not just a picture of space. It was a time machine.

Light from the most distant galaxies in the image had begun its journey when the universe was only a fraction of its current age. Those photons traveled across expanding space for billions of years before finally reaching Hubble’s mirror. What the image captured was a cross-section of cosmic history compressed into a single frame.

Redshift and the Stretching of Time

One of the most profound scientific insights embedded in the Hubble Deep Field involves redshift, the stretching of light caused by the expansion of the universe. As space itself expands, wavelengths of light traveling through it are stretched, shifting toward the red end of the spectrum. The more distant an object, the more its light is redshifted.

In the Deep Field, many galaxies appear unusually red, not because they are intrinsically red, but because their light has been stretched over immense cosmic distances. These galaxies are among the earliest ever observed, existing when the universe was young and still forming its first generations of stars.

Redshift transforms the image into a layered record of time. Nearby galaxies appear relatively sharp and familiar. Distant galaxies grow fainter, smaller, and stranger, reflecting an era when the universe itself was different, denser, and more chaotic. The Deep Field showed that the universe has a history, and that history is written in light.

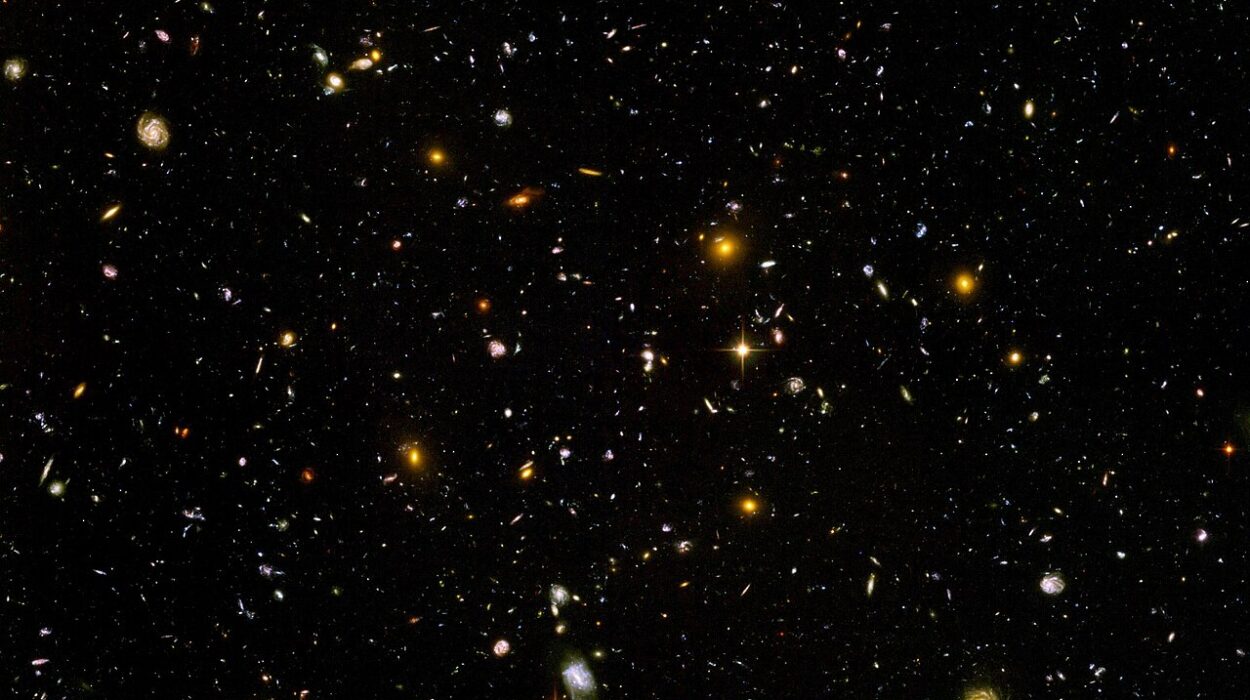

Galaxies Everywhere, Not Just Somewhere

Before the Hubble Deep Field, astronomers knew the universe contained vast numbers of galaxies, but their distribution was uncertain. There was a lingering sense that galaxies might thin out at extreme distances, that perhaps the early universe was sparsely populated or structurally simple.

The Deep Field shattered that notion. It revealed that galaxies are everywhere, even in regions of space that appear empty to casual observation. This implied that galaxy formation began early and occurred efficiently across the cosmos.

The realization carried a quiet philosophical weight. If galaxies fill even the most unassuming patches of sky, then the universe is not centered on anything in particular. There is no privileged direction, no special vantage point. Everywhere you look, if you look deeply enough, the universe reveals itself in overwhelming abundance.

Humanity’s Shrinking Center

Perhaps the most emotionally powerful consequence of the Hubble Deep Field was its impact on human self-perception. For centuries, science has steadily displaced humanity from the center of things. Earth was no longer the center of the solar system. The Sun was not the center of the galaxy. The Milky Way was not the center of the universe.

The Deep Field extended this pattern to an almost unbearable scale. It showed that the tiny region of sky we inhabit is not special. It is statistically ordinary. The galaxies in the image exist in every direction, suggesting that wherever intelligent observers arise, they would see much the same thing.

This realization does not diminish human meaning, but it does challenge human ego. It invites humility without despair. In a universe so vast, our existence is not guaranteed, but it is also not isolated. The same physical laws that shaped those distant galaxies shaped us. The same cosmic processes that forged their stars forged the atoms in our bodies.

Time, Fragility, and Cosmic Perspective

The Deep Field also transformed how we think about time. The image collapses billions of years into a single moment of observation. Galaxies at different distances appear side by side, even though they belong to vastly different eras of cosmic history.

This compression highlights the fragility of the present. Our moment in the universe is brief, balanced between an immense past and an uncertain future. Civilizations rise and fall in a cosmic instant. Species emerge and vanish. Yet the universe persists, evolving slowly, patiently, indifferent to individual moments.

There is a strange comfort in this perspective. It suggests that while our lives are fleeting, they are part of something enduring. The universe is not static or dead. It is a dynamic process, unfolding across scales that dwarf human imagination.

Scientific Consequences and New Questions

Beyond its philosophical impact, the Hubble Deep Field had concrete scientific consequences. It provided direct evidence for theories of galaxy formation and evolution. It confirmed that early galaxies were smaller, more irregular, and more actively forming stars than many modern galaxies.

The image also raised new questions. How did these early galaxies grow so quickly? What role did dark matter play in shaping their structure? How did the first stars influence their surroundings? The Deep Field did not provide all the answers, but it supplied the data that made those questions unavoidable.

In science, progress often comes not from solving mysteries, but from revealing them clearly. The Deep Field did exactly that.

Repetition and Reinforcement

The success of the original Hubble Deep Field inspired subsequent deep observations. Astronomers repeated the experiment in different parts of the sky, producing images that reinforced the original conclusions. Every deep field revealed the same truth: galaxies everywhere, at all observable distances.

These repeated observations strengthened confidence that the Deep Field was not an anomaly. It was representative. The universe, as far as we can see, is richly populated and structured.

Each new deep image added nuance and detail, but the emotional shock of the first one remained unique. There is something singular about the first time humanity truly sees the scale of its surroundings.

Technology as a Bridge to Awe

The Hubble Deep Field also stands as a testament to technology as an extension of human perception. No human eye could ever see what Hubble saw. The image exists only because of engineering, mathematics, and decades of accumulated knowledge.

Yet the result is not cold or mechanical. It is deeply moving. It proves that technology, when guided by curiosity and patience, can deepen our sense of wonder rather than diminish it. The Deep Field is a reminder that science is not the enemy of awe, but one of its greatest sources.

The Image That Refuses to Fade

Decades after its release, the Hubble Deep Field remains one of the most influential images ever produced. It appears in textbooks, documentaries, and philosophical discussions. It is referenced not just by astronomers, but by writers, artists, and thinkers searching for metaphors of scale and meaning.

Its power lies in its simplicity. It does not shout. It does not dramatize. It simply shows what is there, if one is willing to look long enough. In that patience lies its lesson.

A Changed Scale of Reality

Before the Hubble Deep Field, the universe was vast but abstract. After it, vastness became visible. It became personal. The image forced humanity to confront the true scale of reality, not as an idea, but as evidence.

The Deep Field did not answer every question. It did something more important. It changed the questions themselves. It asked us to think bigger, deeper, and with greater humility. It reminded us that reality is not obligated to fit our expectations, but that it rewards curiosity with beauty beyond measure.

In one photograph, taken by a telescope orbiting a small planet around an ordinary star in a typical galaxy, humanity caught a glimpse of its true surroundings. The universe, it turns out, is far more crowded, ancient, and magnificent than we ever dared to imagine.