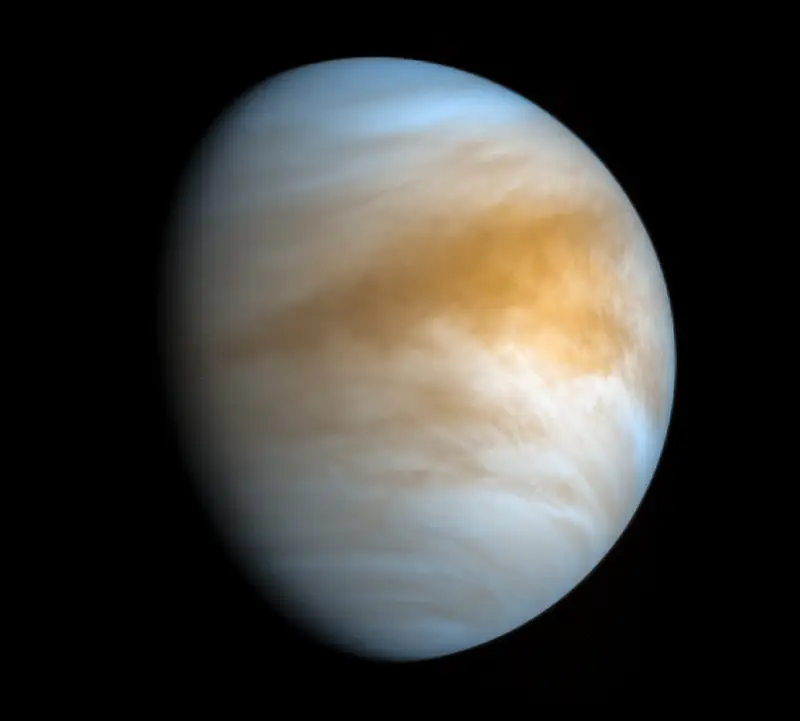

Venus hangs in the sky like a promise and a warning at the same time. To the naked eye, it is beautiful—brilliant, steady, and serene, often called the Morning Star or Evening Star. For ancient civilizations, Venus was a symbol of love, fertility, and divine power. Yet beneath that glowing veil lies one of the most hostile environments in the solar system. Venus is not merely hot; it is crushed by its own atmosphere, scorched by runaway greenhouse heating, and transformed into a world where familiar ideas of weather, water, and life collapse into extremes.

Venus is often described as Earth’s twin. It is similar in size, mass, and composition. It likely formed from the same region of the protoplanetary disk and may once have shared features we associate with habitability. That resemblance makes Venus unsettling. If a planet so much like Earth could become a furnace where lead melts and rocks slowly deform, then Venus is not just another planet. It is a lesson written in stone and cloud, a cautionary tale about climate, chemistry, and planetary fate.

To understand how Venus became a dead world, we must follow the story of its greenhouse effect—how it began, how it spiraled out of control, and how it ultimately locked the planet into a state that has endured for billions of years.

A World That Could Have Been Familiar

When Venus first formed, it was not necessarily destined for hell. Early in the solar system’s history, the young Sun was dimmer than it is today. Under that weaker sunlight, Venus may have had conditions closer to Earth’s than its present inferno suggests. Geological and atmospheric models indicate that Venus could once have possessed significant amounts of water, perhaps even shallow oceans.

Water is not just a passive ingredient in planetary history. It shapes surface geology, moderates climate, and acts as a chemical buffer. On Earth, oceans absorb heat, dissolve gases, and participate in cycles that stabilize temperature over long timescales. If Venus once had liquid water, it may have enjoyed a climate far more temperate than today’s, at least for a time.

The similarity between early Earth and early Venus is the most haunting aspect of Venusian history. Two planets of comparable size and composition took radically different paths. Earth cooled enough to condense oceans, develop plate tectonics, and eventually host life. Venus, closer to the Sun, received more solar energy, pushing it toward a fragile threshold.

The tragedy of Venus is not that it was always hostile, but that it crossed a point of no return.

The Greenhouse Effect as a Natural Force

The greenhouse effect itself is not evil or destructive. It is a natural and necessary process that warms a planet by trapping heat in its atmosphere. On Earth, gases such as water vapor, carbon dioxide, and methane absorb infrared radiation emitted by the surface, preventing all of that heat from escaping into space. Without this effect, Earth would be a frozen world, far too cold for liquid water or life as we know it.

Venus also developed a greenhouse effect early in its history. With more solar energy reaching its surface, Venus naturally retained more heat. Water vapor, a powerful greenhouse gas, would have increased in the atmosphere as temperatures rose. This initial warming may have seemed modest, but it set the stage for something far more dangerous.

Unlike Earth, Venus lacked certain stabilizing mechanisms. Earth’s carbon cycle, driven by plate tectonics and liquid water, gradually removes carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and locks it into rocks. Rain dissolves carbon dioxide, rivers carry it to the oceans, and geological processes bury it over millions of years. Venus, with weaker or absent plate tectonics and increasing surface heat, could not sustain this balancing act.

What began as a normal greenhouse effect began to amplify itself.

The Runaway Begins

As Venus warmed, more water evaporated into the atmosphere. Water vapor is not only a greenhouse gas; it amplifies warming by trapping additional heat. This extra heat caused even more evaporation, which led to more warming, in a self-reinforcing loop known as a runaway greenhouse effect.

This feedback mechanism is brutally simple. Higher temperatures lead to more water vapor. More water vapor leads to stronger heat trapping. Stronger heat trapping leads to higher temperatures. Once this cycle starts, it becomes increasingly difficult to stop.

Eventually, Venus crossed a critical threshold. The planet could no longer cool itself effectively. Any liquid water on the surface boiled away entirely, filling the atmosphere with steam. At that point, Venus lost one of its most important climate regulators.

The oceans, if they existed, were gone.

The Fate of Water on Venus

The loss of liquid water marked a turning point in Venusian history. Without oceans, Venus lost its ability to moderate temperature and absorb atmospheric gases. But water did not simply vanish without leaving a trace.

High in Venus’s atmosphere, ultraviolet radiation from the Sun broke water molecules into hydrogen and oxygen. Hydrogen, being light, escaped into space. Oxygen, heavier and more reactive, likely combined with surface materials or other atmospheric components.

This process permanently dehydrated Venus. Once hydrogen escaped, water could never be reassembled. The planet became locked into a dry state that persists today.

The absence of water had cascading consequences. Chemical weathering slowed to a halt. Surface rocks baked and hardened. Any possibility of life, at least as we understand it, faded away.

Venus did not just lose its oceans. It lost the means to recover them.

Carbon Dioxide Takes Over

As water disappeared, carbon dioxide became the dominant atmospheric gas. On Earth, carbon dioxide is constantly cycled between the atmosphere, oceans, and rocks. On Venus, without water and active geological recycling, carbon dioxide accumulated relentlessly.

Today, Venus’s atmosphere is composed almost entirely of carbon dioxide, with pressures at the surface more than ninety times that of Earth. This crushing atmosphere traps heat with terrifying efficiency. The surface temperature of Venus is hot enough to melt lead and remains nearly uniform across the planet, regardless of latitude or time of day.

Unlike Earth, where temperature varies with seasons and location, Venus exists in a state of thermal imprisonment. Heat cannot escape, and cooling mechanisms are ineffective. The greenhouse effect did not merely warm Venus; it transformed the planet into a pressure cooker sealed for eternity.

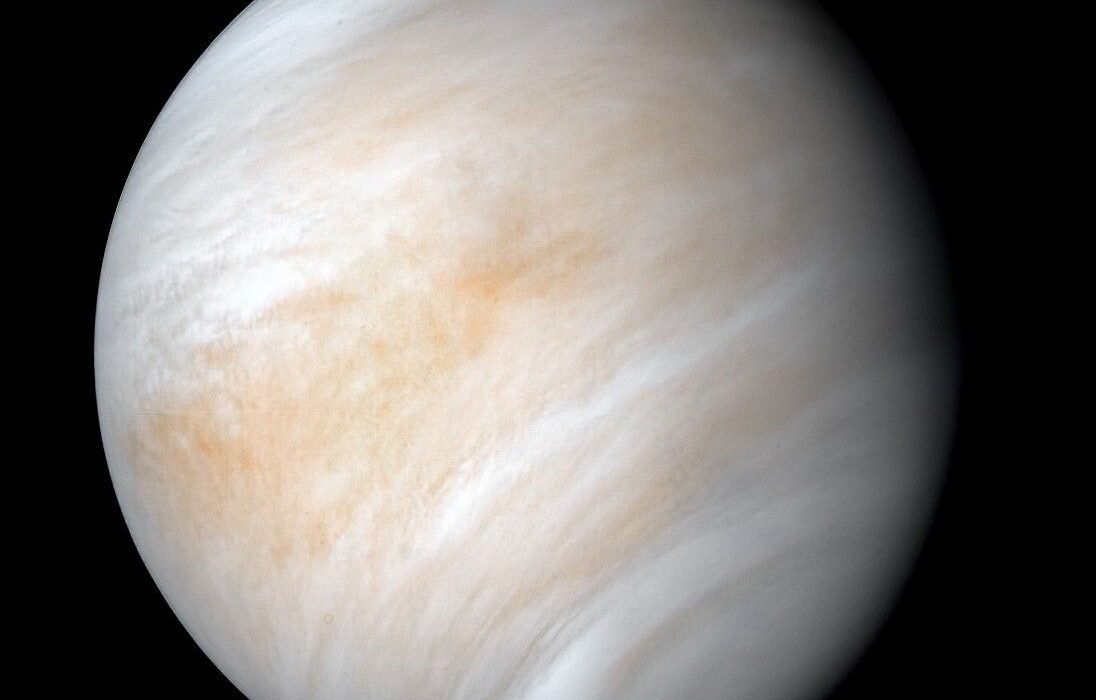

Clouds of Acid and a Sunless Sky

Venus is perpetually hidden beneath thick clouds, but these are not clouds of water vapor. They are composed primarily of sulfuric acid droplets, suspended in the atmosphere by powerful winds. These clouds reflect much of the incoming sunlight, giving Venus its bright appearance from Earth.

Ironically, despite reflecting sunlight, Venus remains scorching hot. The reflection occurs high in the atmosphere, while the dense carbon dioxide below traps infrared heat radiating from the surface. The result is a world that is both reflective and infernal.

The sulfuric acid clouds are a product of volcanic gases interacting with the atmosphere. Sulfur dioxide, released by volcanoes, reacts with trace amounts of water to form sulfuric acid. These clouds rain acid—but the rain never reaches the ground. It evaporates before touching the surface, a ghostly precipitation that never fulfills its promise.

Standing on Venus, if it were possible, one would see a dim, orange-tinted sky. The Sun would appear as a pale blur, its light scattered and muted by the thick atmosphere. Shadows would be faint or nonexistent. The air itself would feel like an ocean pressing down.

A Surface Forged by Heat and Fire

Venus’s surface tells the story of its extreme environment. Radar mapping reveals vast volcanic plains, towering shield volcanoes, and deformed landscapes shaped by intense heat and pressure. Unlike Earth, Venus shows little evidence of plate tectonics. Instead of continents drifting and colliding, Venus’s crust appears to behave as a single, stagnant shell.

This stagnant lid traps heat inside the planet. Over time, internal heat builds until it is released through massive volcanic eruptions. Evidence suggests that Venus may have undergone global resurfacing events, where enormous volumes of lava flooded the surface, erasing older features.

These catastrophic episodes would have released vast amounts of carbon dioxide and sulfur gases into the atmosphere, reinforcing the greenhouse effect. Volcanism did not just shape Venus’s surface; it fed the furnace of its climate.

In this way, Venus entered a feedback loop between geology and atmosphere. Heat drove volcanism. Volcanism released greenhouse gases. Greenhouse gases trapped more heat.

Time Without Mercy

One of the most unsettling aspects of Venus is how stable its hellish state appears to be. For hundreds of millions, perhaps billions, of years, Venus has remained locked in extreme conditions. There is no seasonal relief, no gradual cooling, no sign of recovery.

Time on Venus moves differently in another sense as well. The planet rotates extremely slowly, with a day longer than its year. The Sun rises and sets at a glacial pace, though the surface temperature hardly changes. The atmosphere, however, races around the planet at incredible speeds, completing a full rotation in just a few days.

This disconnect between surface and sky creates an alien rhythm, a reminder that Venus operates according to rules shaped by its unique history.

Why Venus Did Not Become Earth

The question that haunts planetary science is not simply how Venus became hell, but why Earth did not follow the same path. The answer lies in a delicate balance of distance, chemistry, and chance.

Earth orbits slightly farther from the Sun, receiving less solar energy. That difference, though modest, was enough to allow oceans to form and persist. Liquid water enabled Earth’s carbon cycle, stabilizing climate over geological timescales.

Earth also developed active plate tectonics, which recycle carbon and regulate surface temperature. Venus, with its hotter interior and lack of water-lubricated crust, never developed the same tectonic behavior.

Small initial differences led to divergent outcomes. Venus crossed the runaway greenhouse threshold. Earth did not.

This realization gives Venus its power as a warning. Planetary habitability is not guaranteed. It depends on maintaining balance, and that balance can be lost.

Lessons from a Dead World

Venus is more than a scientific curiosity. It is a natural experiment in climate extremes. By studying Venus, scientists gain insight into how greenhouse effects operate at their most intense and how planetary systems can spiral beyond control.

Venus shows that greenhouse warming does not require exotic conditions. It can arise from familiar gases behaving under familiar physics, given enough time and the wrong circumstances. It demonstrates that once certain thresholds are crossed, reversing the process may be impossible.

This does not mean Earth is destined to become Venus. The timescales, mechanisms, and current conditions are vastly different. But Venus reminds us that climate systems have tipping points and that stability is not eternal.

Searching for Life in the Ruins

Despite its hostility, Venus has not been completely abandoned as a candidate for life’s study. Some scientists have speculated about the possibility of microbial life in the planet’s upper atmosphere, where temperatures and pressures are more moderate. These ideas remain controversial and unproven, but they reflect humanity’s refusal to stop asking questions, even in the most unlikely places.

Whether or not life ever existed on Venus, its current state appears profoundly inhospitable. The surface is sterile, the air toxic, and the conditions unforgiving. Venus is, by any reasonable definition, a dead world.

Yet it is a dead world with a voice.

Venus as a Mirror

When we look at Venus, we are not just observing another planet. We are glimpsing an alternate history of Earth, a version of events where balance was lost and recovery was impossible. Venus is a mirror that shows us what happens when natural processes run unchecked.

This mirror is not meant to terrify, but to educate. Venus teaches us about climate feedbacks, planetary evolution, and the fragility of habitability. It shows us that beauty and danger can coexist, that a bright planet can hide unimaginable extremes.

Venus reminds us that planets are not static objects. They are dynamic systems shaped by physics, chemistry, and time. They can nurture life, or they can destroy the conditions that make life possible.

The Silent Planet That Still Speaks

Venus will never cool enough for oceans to return. Its water is gone, its atmosphere locked into a suffocating embrace, its surface reshaped by relentless heat. In cosmic terms, its fate is sealed.

And yet, Venus continues to matter.

It matters because it expands our understanding of how worlds work. It matters because it challenges our assumptions about habitability. It matters because it stands as a natural warning written not by humans, but by the universe itself.

In the end, Venusian hell is not just about fire and pressure and acid clouds. It is about consequences. It is about how small differences can lead to radically different outcomes. It is about how a greenhouse effect, so essential to life on one world, became the architect of death on another.

Venus is silent, but its lesson echoes across the solar system.