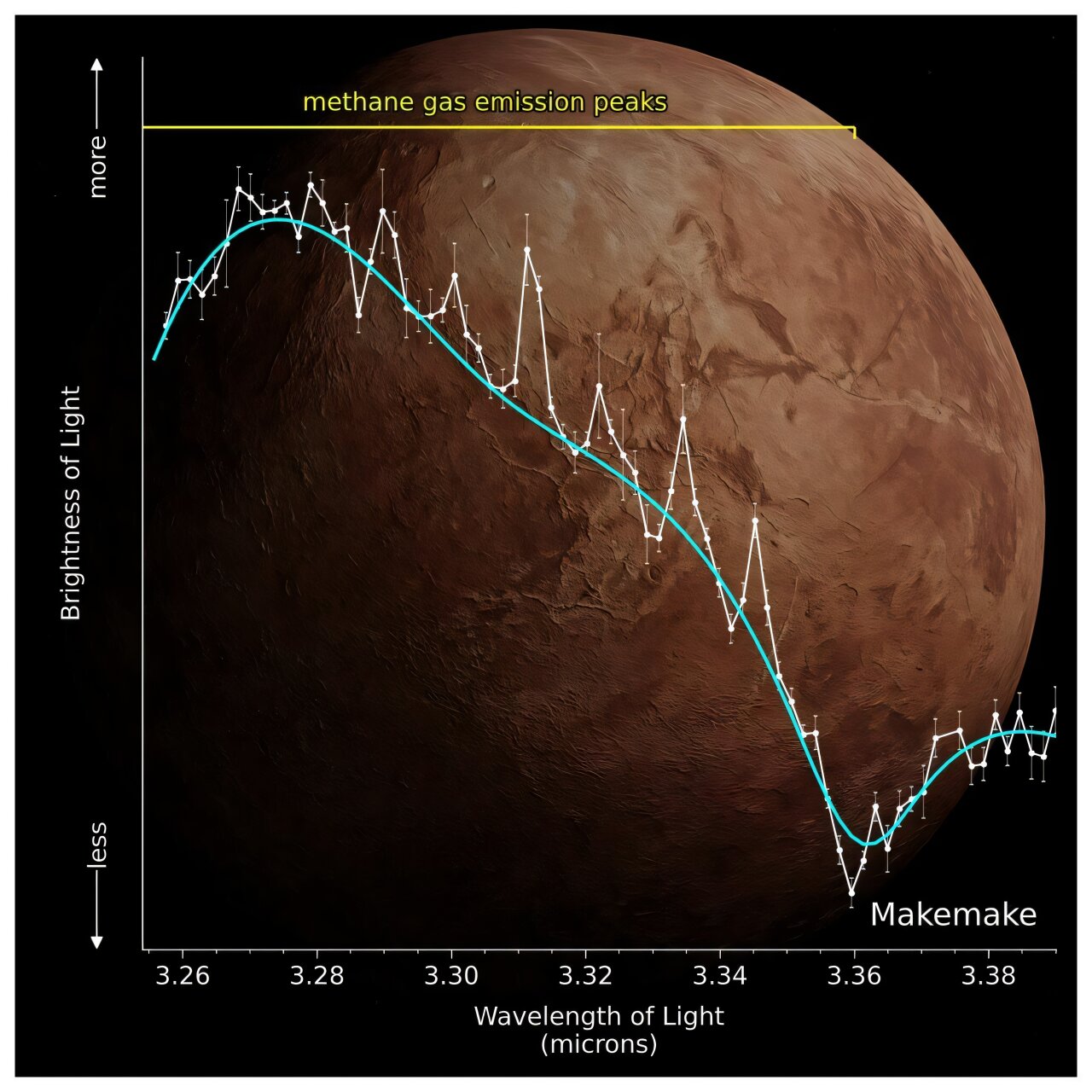

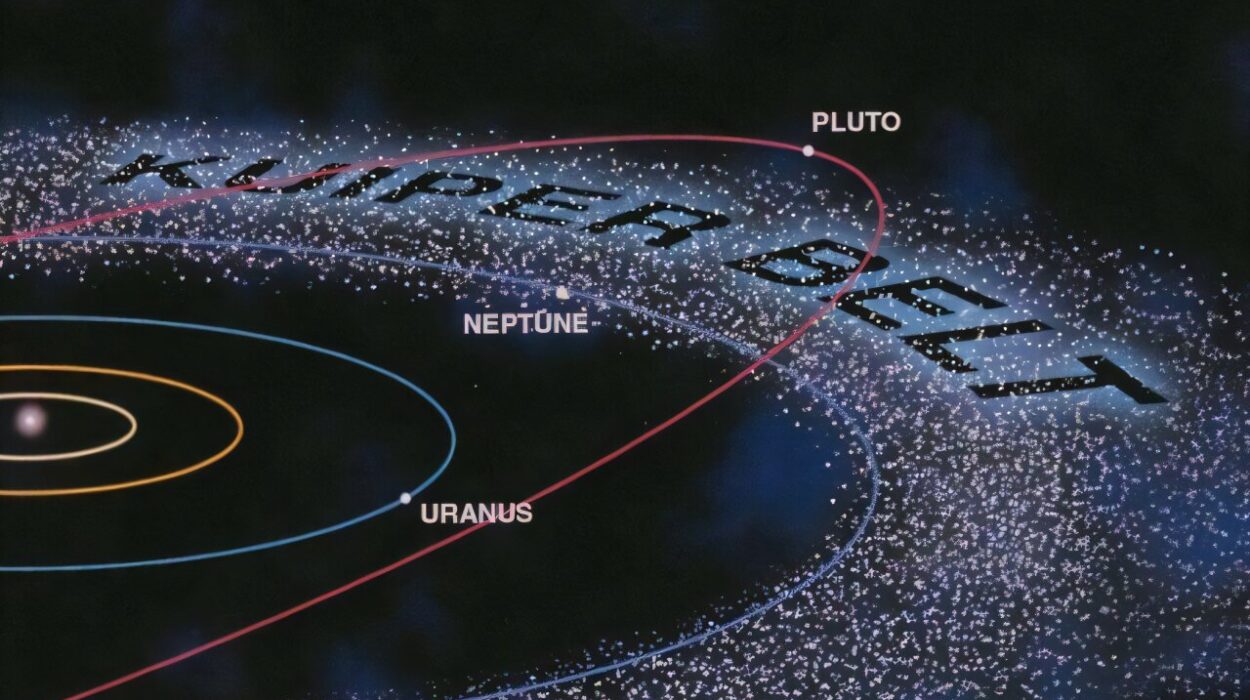

For decades, Makemake has been one of the most enigmatic residents of the Kuiper Belt—the icy frontier of our solar system beyond Neptune. Known as one of the largest and brightest dwarf planets, Makemake seemed like a silent, frozen relic of cosmic history. But now, thanks to the keen eyes of NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), scientists have uncovered something astonishing: the first detection of methane gas above Makemake’s surface.

This discovery transforms our picture of the distant world. It suggests that Makemake is not a static, frozen rock drifting through space, but a dynamic, evolving body with subtle processes still shaping its surface and atmosphere.

A World of Methane Ice

Makemake, stretching about 890 miles (1,430 kilometers) across—roughly two-thirds the size of Pluto—has long intrigued planetary scientists. Its reflective surface, bright even from billions of miles away, told us it was covered in methane ice. But the JWST has now revealed something new: methane is not only locked in ice but also exists as gas hovering above the surface.

Dr. Silvia Protopapa of the Southwest Research Institute, lead author of the study, emphasized the significance of this finding: “The Webb telescope has now revealed that methane is also present in the gas phase above the surface, a finding that makes Makemake even more fascinating. It shows that Makemake is not an inactive remnant of the outer solar system, but a dynamic body where methane ice is still evolving.”

The methane gas was detected through a phenomenon called solar-excited fluorescence—sunlight absorbed by methane molecules and then re-emitted as distinctive spectral signals.

A Fragile Atmosphere or Bursts of Activity?

The discovery raises profound questions. What exactly is happening on Makemake?

One possibility is that the methane represents a tenuous, planet-wide atmosphere, in delicate balance with the methane ice on the surface—much like Pluto’s faint but persistent atmosphere. If true, Makemake would be breathing, albeit faintly, as frozen methane sublimates into gas and then settles back as frost.

Another possibility is more dramatic: transient outbursts of methane, driven by sublimation or even cryovolcanic plumes—jets of gas erupting from beneath the icy crust. If this is the case, Makemake may be far more active than previously imagined, with localized hot spots fueling episodic releases of gas.

Dr. Emmanuel Lellouch of the Paris Observatory highlighted just how delicate this methane presence might be: “Our best models point to a gas temperature around 40 Kelvin (–233 degrees Celsius) and a surface pressure of only about 10 picobars—that is, 100 billion times below Earth’s atmospheric pressure, and a million times more tenuous than Pluto’s.”

Such a fragile envelope of gas would be incredibly difficult to detect without Webb’s unparalleled sensitivity, making this discovery a technical triumph as well as a scientific one.

Clues from Puzzling Anomalies

Hints that Makemake might harbor unusual activity had been accumulating for years. Stellar occultations—events where Makemake passes in front of a distant star—suggested that it lacked a substantial global atmosphere, but left open the possibility of a thin one. Meanwhile, infrared observations revealed thermal anomalies across its surface, suggesting areas warmer than expected.

These findings puzzled scientists. What could explain patches of unexpected heat on a world so far from the Sun? The presence of methane gas adds another piece to this puzzle. Outgassing or localized sublimation could explain both the spectral oddities and the thermal irregularities.

Dr. Ian Wong of the Space Telescope Science Institute noted: “While the temptation to link Makemake’s various spectral and thermal anomalies is strong, establishing the mechanism driving the volatile activity remains a necessary step toward interpreting these observations within a unified framework.”

Echoes of Other Worlds

Makemake’s potential activity places it in distinguished company. Pluto is known to have a thin, evolving atmosphere of nitrogen and methane. Neptune’s moon Triton has been caught releasing nitrogen plumes. Saturn’s moon Enceladus erupts with geysers of water vapor and ice grains. Even Ceres, a dwarf planet in the asteroid belt, has shown faint signs of water vapor.

If Makemake is venting methane in plumes, it could rival or even exceed some of these worlds in vigor. Models suggest that such plumes could release hundreds of kilograms of methane per second—comparable to the famous water geysers of Enceladus.

This raises the possibility that volatile-driven activity is more common in the outer solar system than once believed, hinting that these distant worlds are far from inert. Instead, they may be dynamic laboratories where ice, gas, and sunlight continue to interact in surprising ways.

A Glimpse into the Kuiper Belt’s Secrets

The Kuiper Belt, a vast expanse of icy worlds orbiting beyond Neptune, is thought to preserve the building blocks of the solar system. Studying these bodies offers a window into the conditions that shaped planets and moons billions of years ago.

Makemake’s newly detected methane gas underscores the complexity of these distant objects. Rather than being frozen fossils, they may be evolving worlds with active processes that echo the early solar system. Each discovery peels back another layer of mystery, reminding us how little we truly know about the frontier beyond Neptune.

What Comes Next

The Webb telescope has only just begun its exploration of Makemake. Future observations, with higher spectral resolution, may distinguish whether the methane gas is part of a thin, persistent atmosphere or the product of sporadic outbursts.

Whatever the outcome, Makemake has already changed in our imagination—from a quiet, icy rock to a world with whispers of activity. Its methane gas tells us that even in the cold darkness of the Kuiper Belt, planets can breathe, evolve, and surprise us.

As Dr. Protopapa reflected, the discovery is not just about one dwarf planet—it is about reshaping how we see the solar system’s distant frontier. “This shows us that the Kuiper Belt is not a graveyard of frozen relics,” she suggested. “It is a living region, filled with dynamic worlds.”

A Universe Still Speaking

Makemake’s faint methane glow, captured across the gulf of billions of miles, is more than a scientific data point—it is a reminder that the universe still holds secrets waiting to be heard. Each discovery with Webb is like a whispered message from the cosmos, urging us to look closer, think deeper, and marvel at the unexpected vitality of even the most distant worlds.

In the fragile breath of methane above Makemake, we glimpse not just the life of a dwarf planet, but the vitality of the solar system itself—restless, evolving, and endlessly surprising.

More information: Silvia Protopapa et al, JWST Detection of Hydrocarbon Ices and Methane Gas on Makemake, arXiv (2025). DOI: 10.48550/arxiv.2509.06772