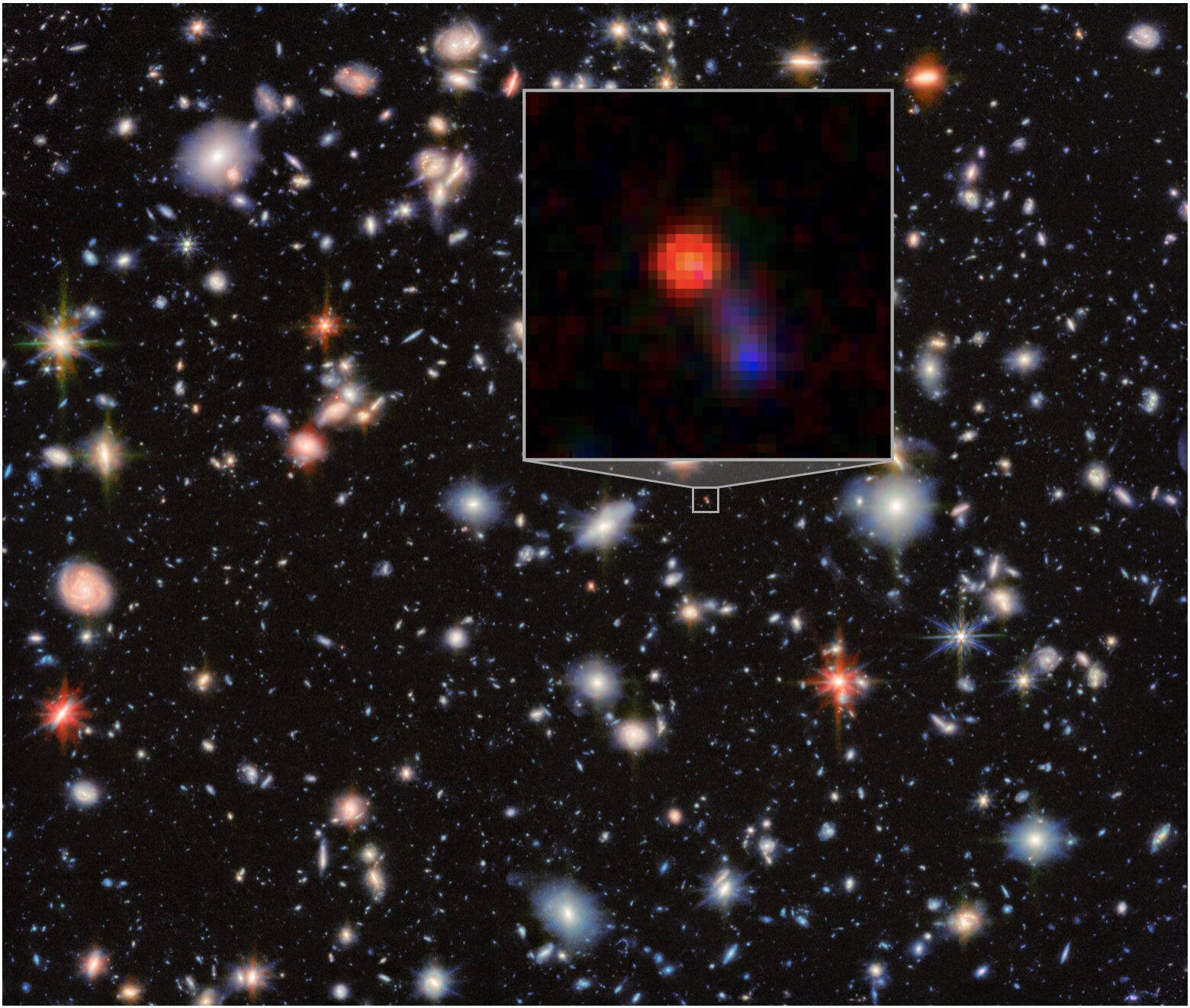

In the faint afterglow of the early cosmos, astronomers have stumbled upon a galaxy that refuses to behave as it should. Seen as it existed just 800 million years after the Big Bang, the object known as Virgil first appears to be an ordinary citizen of the young universe. Through visible and ultraviolet light, it resembles a typical star-forming galaxy—bright, compact, and unremarkable in a crowded sky.

But when astronomers turned their attention to longer wavelengths, Virgil revealed another side of its story. What looked peaceful in optical light erupted into something far more dramatic in the infrared. It was a startling transformation, as if the galaxy had been living a double life across the spectrum. Virgil is, in the words of the scientists who analyzed it, a cosmic Jekyll and Hyde.

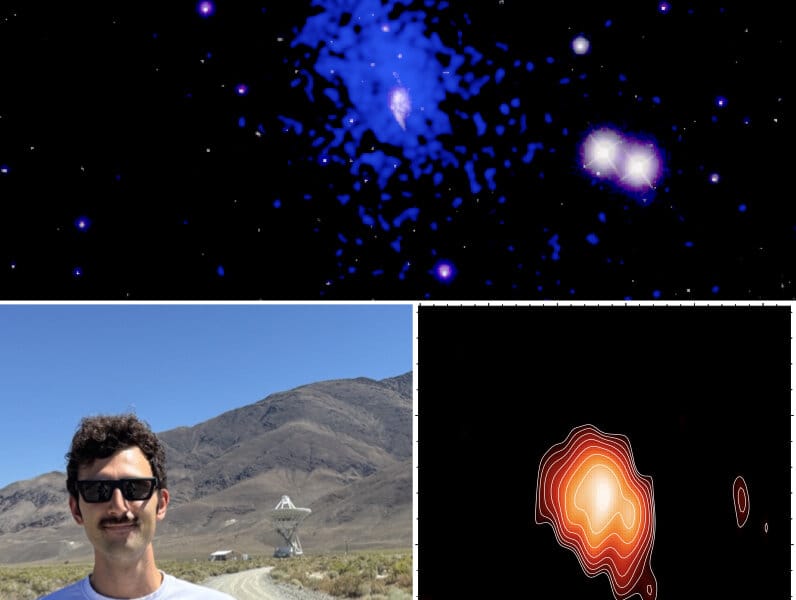

This discovery, led by George Rieke and Pierluigi Rinaldi and published in The Astrophysical Journal, now threatens to overturn long-standing assumptions about how black holes and galaxies formed in the early universe.

The Moment a Monster Stepped Out of the Dark

Astronomers already knew this galaxy. But with new data from NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), its familiar face gave way to something wholly unexpected. Beneath dense curtains of dust, a supermassive black hole sits at Virgil’s center, devouring matter at an extraordinary rate and unleashing immense energy into its surroundings. That energy was invisible at shorter wavelengths, absorbed and hidden by the dust. But in the infrared, it blazed into view.

The mass of this black hole is shockingly high for such a young cosmic era. More importantly, it is far larger than the galaxy itself should be capable of sustaining. Scientists call such objects “overmassive” black holes, and they are rare outliers that challenge standard models of cosmic evolution.

For decades, astronomers believed that galaxies came first, providing the raw material for black holes to grow slowly over time. But the evidence gathered from Virgil tells a different story. As Rieke put it, “JWST has shown that our ideas about how supermassive black holes formed were pretty much completely wrong.” He added, “It looks like the black holes actually get ahead of the galaxies in a lot of cases. That’s the most exciting thing about what we’re finding.”

Virgil is not only an exception—it may be a sign that the early universe was filled with far more unruly objects than anyone expected.

The Rise and Mystery of the Little Red Dots

Virgil’s discovery pulls it into an enigmatic class of objects called Little Red Dots, or LRDs. These compact, extremely red sources were first uncovered by JWST, their reddish glow the result of cosmic expansion stretching their light to longer wavelengths during the long journey to us. LRDs burst into abundance roughly 600 million years after the Big Bang, only to fade from the cosmic record about 900 million years later.

Their origins remain a matter of intense debate. Some astronomers suggest they represent rapid, dust-shrouded star formation. Others have proposed more exotic explanations. But Virgil stands out among them all—it is the reddest source yet found in the entire population.

This raises a compelling question. If LRDs once thrived in such great numbers, where are their descendants today? “Nothing can leave our universe,” the researchers note, meaning their modern counterparts must still exist, hidden somewhere in the cosmic web.

Virgil’s peculiar nature hints at an answer. Perhaps many LRDs were not exotic star clusters at all, but instead galaxies hiding voracious, dust-embedded black holes like the one at Virgil’s core.

When Technology Becomes a Cosmic Detective

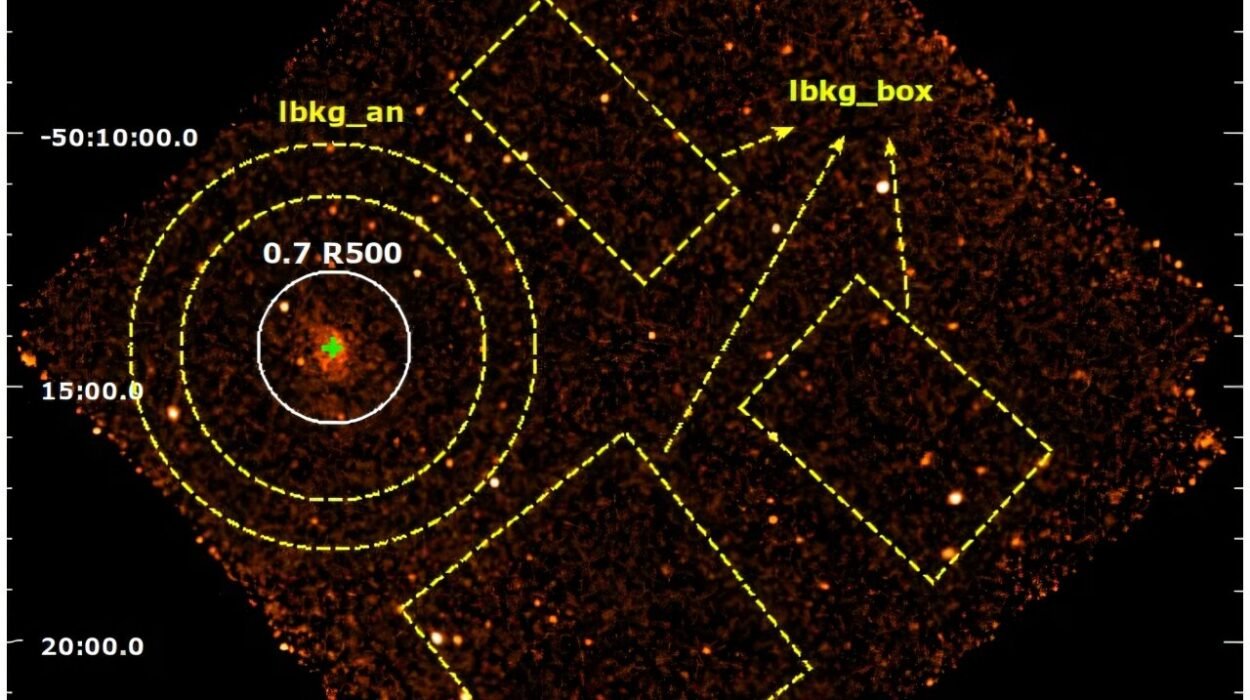

Virgil’s double identity only became visible because of JWST’s Mid-Infrared Instrument, or MIRI. While the telescope’s Near Infrared Camera (NIRCam) and Near-Infrared Spectrograph (NIRSpec) revealed nothing unusual, MIRI exposed the powerful, obscured black hole whose energy dominates the galaxy’s infrared signature.

“Virgil has two personalities,” said Rieke. “The UV and optical show its ‘good’ side—a typical young galaxy quietly forming stars. But when MIRI data are added, Virgil transforms into the host of a heavily obscured supermassive black hole pouring out immense quantities of energy.”

Rinaldi, whose doctoral work focused on MIRI observations, emphasized just how crucial the instrument is for studying such cosmic chameleons. “MIRI basically lets us observe beyond what UV and optical wavelengths allow us to detect,” he said. “It’s easy to observe stars because they light up and catch our attention. But there’s something more than just stars, something that only MIRI can unveil.”

Without MIRI’s ability to probe longer wavelengths—light invisible to human eyes—the black hole would have remained undetected. This reveals a critical blind spot in many JWST surveys: deep imaging with NIRCam is common, but MIRI exposures are often shallow because they require much more observing time. As a result, entire categories of hidden objects may be slipping through the cracks.

A Universe Full of Hidden Giants?

The implications of this blind spot ripple through early cosmic history. If galaxies like Virgil are common, astronomers may be overlooking a substantial population of dust-enshrouded black holes that influenced the universe during some of its most formative epochs.

Some of these objects may even have contributed to cosmic reionization, the pivotal era roughly 100–200 million years after the Big Bang “when the universe decided to light up with stars,” as Rinaldi described it. Yet without deeper mid-infrared observations, their role remains largely invisible.

The extraordinary nature of Virgil—its extreme redness, its overmassive black hole, its early appearance in the universe—has no known counterparts at similar cosmic distances. But the team suspects this may simply reflect the limitations of current observations rather than true cosmic rarity.

Rinaldi captured the mystery succinctly: “Are we simply blind to its siblings because equally deep MIRI data have not yet been obtained over larger regions of the sky?” With more deep mid-infrared imaging, astronomers hope to discover whether Virgil stands alone or whether it is merely a harbinger of an unseen population of ancient cosmic giants.

“JWST will have a fascinating tale to tell as it slowly strips away the disguises into a common narrative,” Rinaldi added.

Why This Discovery Matters

Virgil’s story reaches far beyond a single galaxy. It forces astronomers to rethink the early universe, upending long-held beliefs about the relationship between galaxies and the black holes that anchor them. Instead of slow, synchronized growth, the new evidence suggests that black holes may have surged ahead early on, shaping their galaxies from the inside out.

This discovery also exposes a major observational gap. Without deep mid-infrared data, the universe’s most extreme objects—its hidden black holes, cloaked in dust—may remain invisible, leaving our cosmic history incomplete. Virgil serves as both a revelation and a warning: many of the universe’s earliest and most influential objects may still be hiding in plain sight, waiting for the right wavelength to uncurl their secrets.

The tale of Virgil is a reminder that the universe is not merely observed—it is uncovered, layer by layer, wavelength by wavelength. And JWST, with its ability to peer beyond the light our eyes can see, is just beginning to tell the story.

More information: Pierluigi Rinaldi et al, Deciphering the Nature of Virgil: An Obscured Active Galactic Nucleus Lurking within an Apparently Normal Lyα Emitter during Cosmic Reionization, The Astrophysical Journal (2025). DOI: 10.3847/1538-4357/ae089c