For nearly fifty years, astronomers believed they understood how light emerges from the hearts of quasars, those cosmic lighthouses blazing at the edges of the universe. Their brilliance seemed to follow a simple rule linking ultraviolet glow and X-ray fire, a rule so dependable it became a cornerstone of how scientists map the universe itself. But a new study led by the National Observatory of Athens has uncovered something unsettling. The universe, it seems, has changed its mind.

Compelling evidence now suggests that the structure of matter surrounding supermassive black holes has not remained constant across cosmic time. If true, this finding challenges a law old enough to feel foundational, yet suddenly fragile. The universe we see today may be very different from the universe that was alive billions of years ago.

The Blinding Hearts of Ancient Galaxies

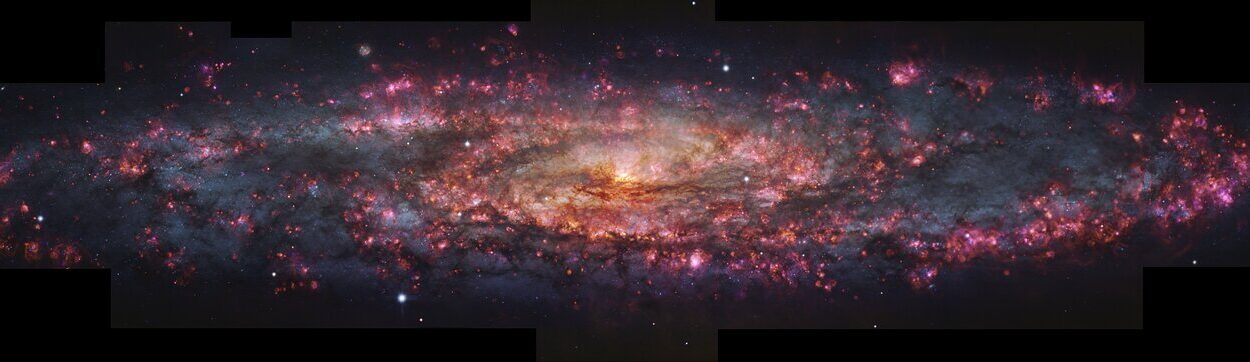

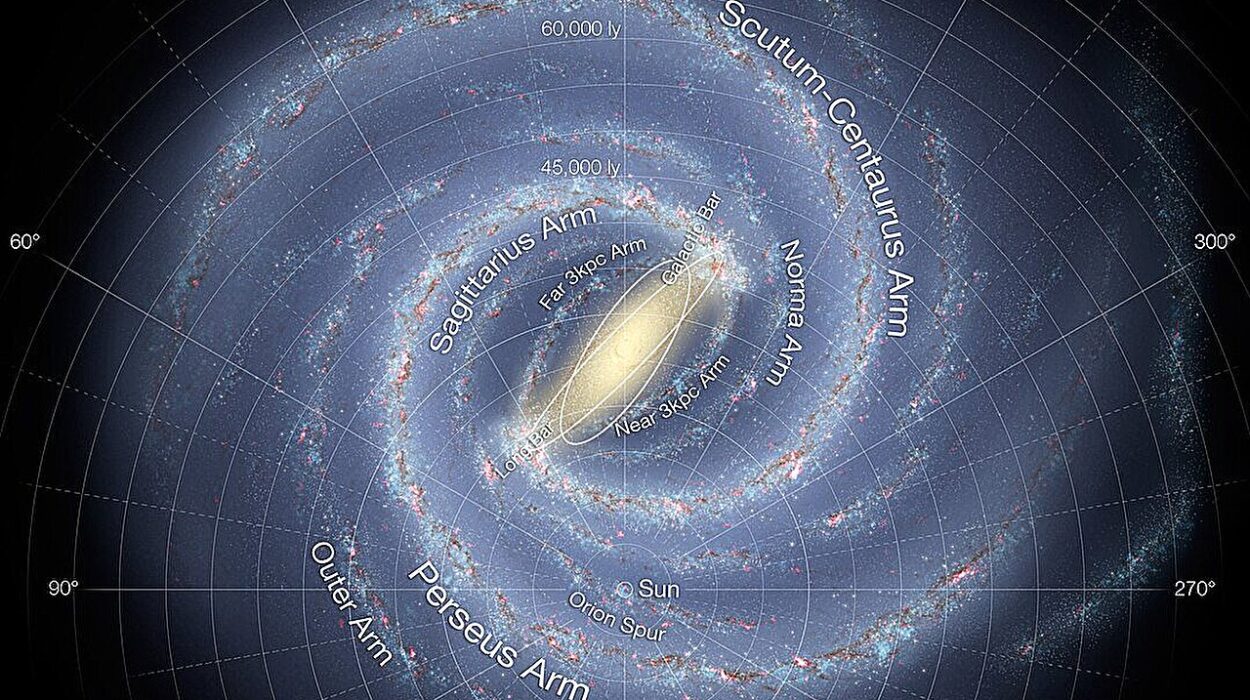

Quasars were first identified in the 1960s, quickly recognized as some of the brightest objects ever observed. Their power comes from the violent intimacy of matter collapsing toward a supermassive black hole. As material spirals inward, it forms a disk that glows fiercely from the heat of friction. This disk becomes so luminous that it can shine 100 to 1,000 times brighter than an entire galaxy of 100 billion stars.

The ultraviolet light produced by the disk is not just an illumination. It is fuel. As the ultraviolet rays cut through the small region near the black hole, they strike clouds of highly energetic particles known as the corona. The ultraviolet light ricochets off these particles and is boosted into X-rays, creating the intense radiation that astronomers use to detect quasars across unimaginable distances.

Because the ultraviolet light and X-ray light share this intimate origin, their relationship has always been tight. More ultraviolet light meant stronger X-rays. Less ultraviolet meant weaker X-rays. This connection seemed universal, constant across the cosmos, a dependable rule woven into the structure of space itself.

Until now.

When the Past Refuses to Match the Present

The latest research paints a very different picture. The team discovered that the relationship between ultraviolet and X-ray light was not the same when the universe was younger. When the cosmos was roughly half its current age, the ultraviolet-to-X-ray link behaved differently—significantly so.

The implication is profound. It suggests that the physical bond between a quasar’s disk and its corona has evolved over the last 6.5 billion years. Something about the way supermassive black holes feed, heat, and radiate may have shifted as the universe aged.

“Confirming a non-universal X-ray-to-ultraviolet relation with cosmic time is quite surprising and challenges our understanding of how supermassive black holes grow and radiate,” said Dr. Antonis Georgakakis, one of the study’s authors. “We tested the result using different approaches, but it appears to be persistent.”

A rule once thought to be unbreakable now appears to be a chapter in the universe’s evolutionary story. The cosmos is not static. Neither are its brightest beacons.

Light That Redraws the Universe

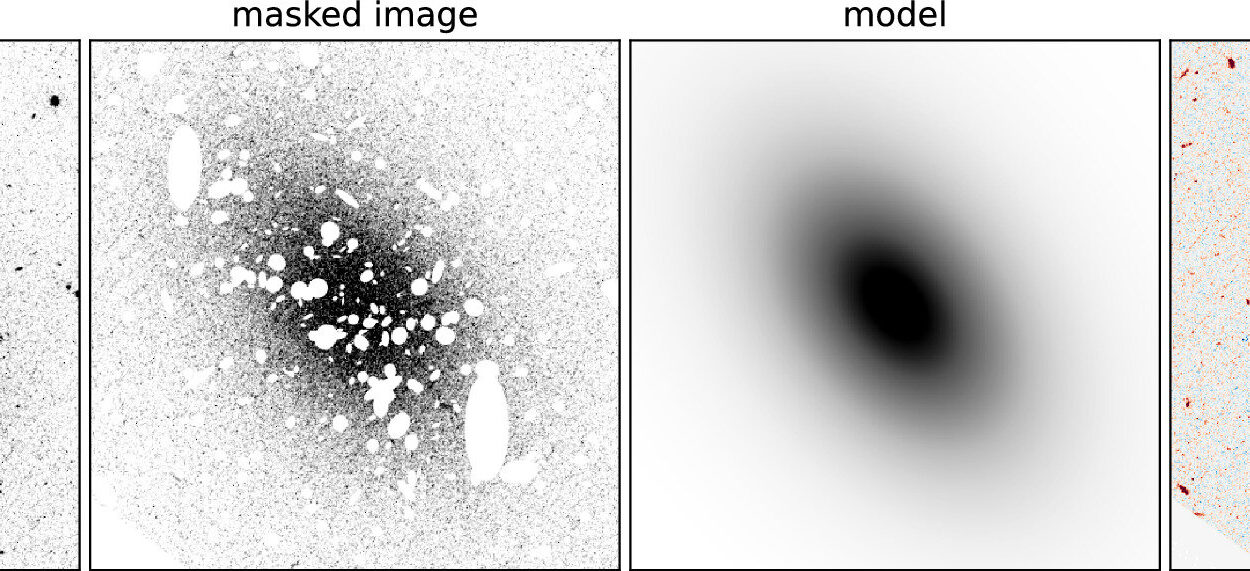

To uncover this shift, the researchers joined forces with two major X-ray observatories. New data from the eROSITA telescope, combined with archival observations from ESA’s XMM-Newton, created the largest sample of quasars ever used to measure this relationship. The wide and uniform coverage from eROSITA played a decisive role, offering a panoramic X-ray view unlike anything collected before.

This discovery has consequences far beyond quasar physics. For years, astronomers have used quasars as “standard candles,” reliable light sources that help measure distances across the universe. The consistency of the ultraviolet-to-X-ray relation made this possible. If that consistency is an illusion—if the relation changes over cosmic time—then the tools used to probe dark matter and dark energy may need to be sharpened, recalibrated, or even reimagined.

A small shift in the universe’s past could ripple into some of the biggest questions about its structure today.

The Hidden Patterns Brought to Light

For Maria Chira, the lead author, the breakthrough was not just about the data but about how the data were handled.

“The key advance here is methodological,” she explained. “The eROSITA survey is vast but relatively shallow—many quasars are detected with only a few X-ray photons. By combining these data in a robust Bayesian statistical framework, we could uncover subtle trends that would otherwise remain hidden.”

The result is a portrait painted from faint strokes, a pattern emerging only when thousands of weak signals are woven together. It is the scientific equivalent of hearing a distant melody by gathering every whisper of sound from across a vast field.

And the melody, once reconstructed, tells a surprising story.

What Remains Unanswered

The discovery opens a new realm of mysteries. Did the structure of accretion disks and coronas truly evolve over billions of years, or are astronomers seeing the effects of subtle observational biases. The full set of eROSITA all-sky scans, not yet completely analyzed, promises to push farther into faint and distant quasars. With more data will come clearer answers.

Future X-ray and multiwavelength surveys will play a crucial part as well. Each new telescope will sharpen the image of how supermassive black holes ignite their surrounding matter, and how that ignition has changed as the universe stretched, cooled, and aged.

For now, the cosmos keeps its secrets, revealing only that the past was stranger than expected.

Why This Discovery Matters

At first glance, a shift in the relationship between ultraviolet and X-ray emissions might seem like a small, technical detail. But it touches on some of the deepest questions in modern astronomy.

If quasars have changed, then so has the environment around the most massive black holes in the universe. Their feeding habits, their radiation processes, and their very structure may be evolving. This challenges the idea that these cosmic engines are timeless.

If the ultraviolet-to-X-ray relation is not universal, then methods used to measure the geometry of the universe must be tested anew. Dark matter and dark energy—two of the biggest enigmas in physics—are explored using tools that depend on reliable distances. This discovery suggests those tools may require careful reconsideration.

Most importantly, this research reminds us that the universe is alive with change. Patterns that seem eternal may quietly bend across billions of years, waiting for the right instruments and the right questions to reveal the truth.

The cosmos is not finished surprising us.

More information: Maria Chira et al, Revisiting the X-ray-to-UV relation of quasars in the era of all-sky surveys, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society (2025). DOI: 10.1093/mnras/staf1905