In the vast quiet of space, where stars burn in silence and planets spin in shadows, a small flicker was all it took to set astronomers on a journey across 117 light-years. That flicker—an almost imperceptible dip in starlight—was captured by NASA’s Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS), and it led to the discovery of one of the most extreme exoplanets found so far: TOI-2431 b.

Orbiting its host star every 5.4 hours—less than a quarter of an Earth day—TOI-2431 b doesn’t just flirt with its star’s light. It practically hugs it. So close is this newly discovered planet to its parent star that its surface, if it has one, may be a molten sea of rock, warped and squeezed by gravitational tides that twist it into something far from spherical.

While Earth takes a leisurely 365 days to journey around the Sun, TOI-2431 b races through its orbit in just over five hours. It’s one of the shortest orbital periods ever observed, earning it the classification of a USP—an ultra-short period planet. The very idea challenges our understanding of what planets can endure.

A Planet Born of Flickers and Precision

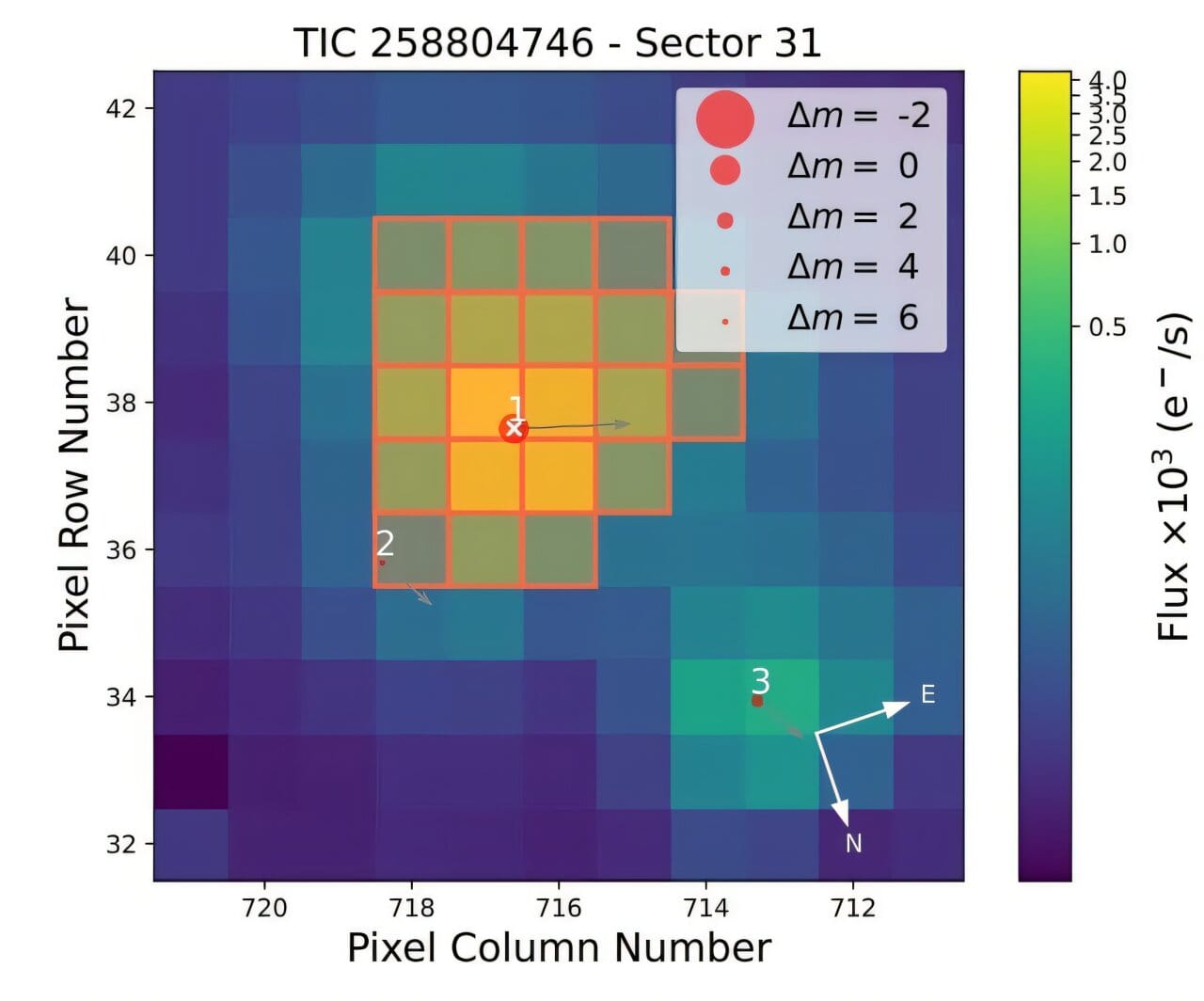

TOI-2431 b first revealed itself not through a photograph or dramatic telescope image, but as a brief, rhythmic darkening in a distant star’s light curve—light recorded by TESS, which has been watching the skies since 2018. TESS, a sentinel in orbit, scans over 200,000 nearby stars, looking for tiny eclipses—moments when planets pass in front of their stars, casting shadows detectable from light-years away.

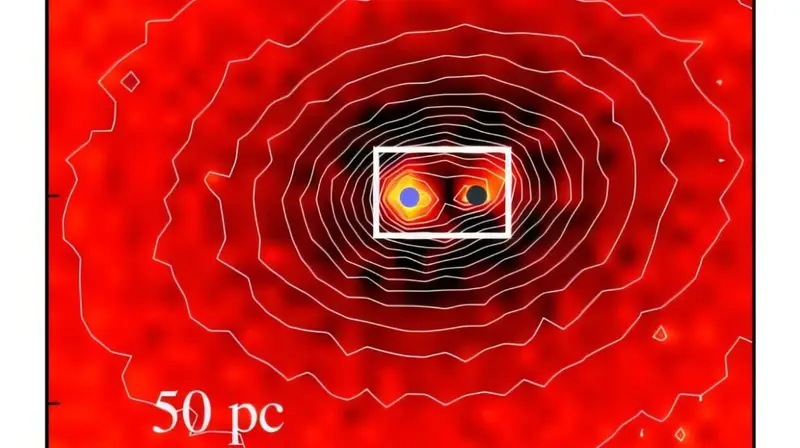

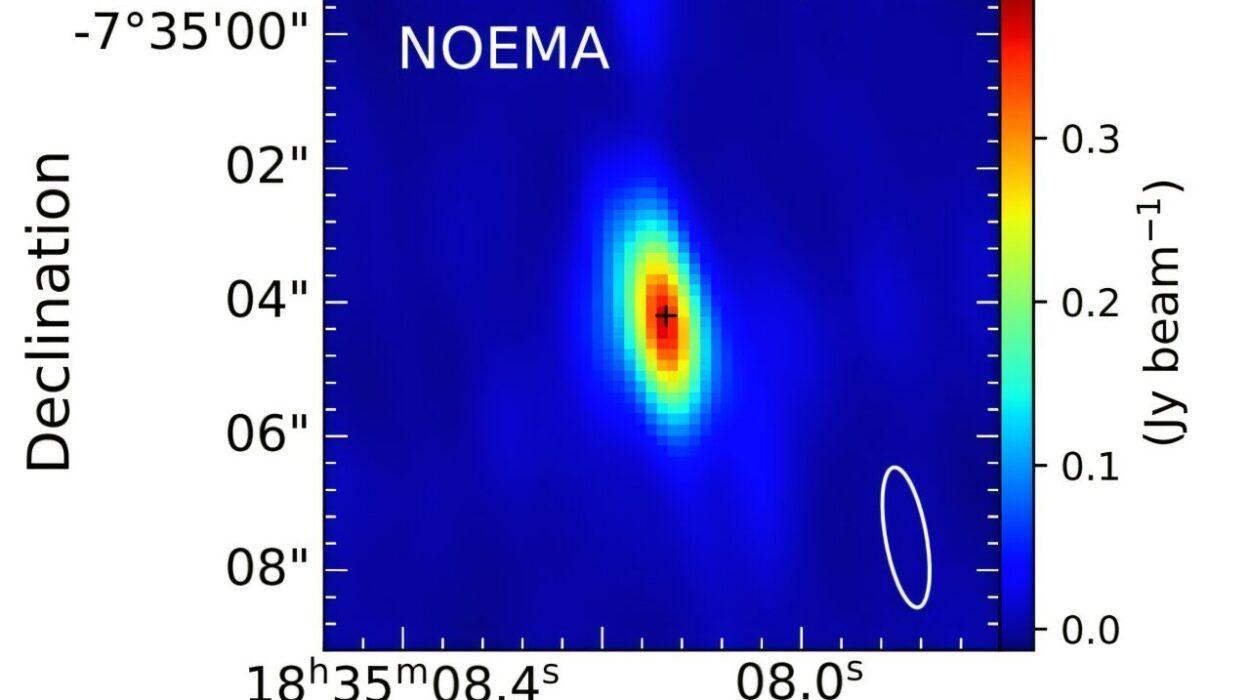

This shadow, associated with a star known as TOI-2431 (short for TESS Object of Interest 2431), hinted at something intriguing. To uncover its true nature, an international team of astronomers led by Kaya Han Taş of the University of Amsterdam stepped in. They confirmed the planet’s existence using a blend of photometric data, radial velocity measurements, and high-resolution speckle imaging, bringing together some of the most advanced tools available—like NEID, HPF, and NESSI.

Through this layered approach, they measured not only the planet’s size and orbit, but its density, temperature, and even its likely shape—an astonishing level of detail for a world more than a hundred light-years away.

TOI-2431 b: A Planet of Fire and Gravity

TOI-2431 b is only about 1.53 times the size of Earth, but it packs more than six times Earth’s mass, giving it a density of 9.4 grams per cubic centimeter. This suggests a world dominated by rock and metal—heavy, compact, and resilient. Yet, for all its toughness, the planet lives in a state of constant torment.

Orbiting just 0.0063 astronomical units (AU) from its host star—roughly twenty times closer than Mercury is to our Sun—TOI-2431 b is scorched by starlight. With an equilibrium temperature of about 2,000 Kelvin (over 3,100 degrees Fahrenheit), its surface is likely a molten, volcanic nightmare, where rock flows like water and metal may vaporize into the sky—if the planet has any atmosphere left at all.

And gravity, too, plays its part in sculpting this tortured world. TOI-2431 b is thought to be tidally deformed—not a perfect sphere, but more like a squashed ellipsoid, stretched and squeezed by the immense gravitational pull of its star. Its shortest axis may be about 9% shorter than its longest—a subtle but important hint of the tidal forces shaping its very structure.

Such deformation is not just cosmetic. It reveals that the planet is likely tidally locked, always showing the same face to its star, like the Moon does to Earth. One hemisphere would be in perpetual daylight—forever molten—while the other remains in eternal, glowing twilight, kept warm by internal heat and star-borne radiation wrapping around from its tortured sunward side.

A Star Smaller Than the Sun, but Just as Furious

The parent star, TOI-2431, is a K-type dwarf, smaller and cooler than our Sun, with about two-thirds its mass and size. With a temperature of 4,109 Kelvin, it might seem gentle by stellar standards. But to TOI-2431 b, it’s a merciless overlord. The planet’s tight orbit means it’s bombarded by intense radiation and gravitational energy, making survival—let alone habitability—impossible.

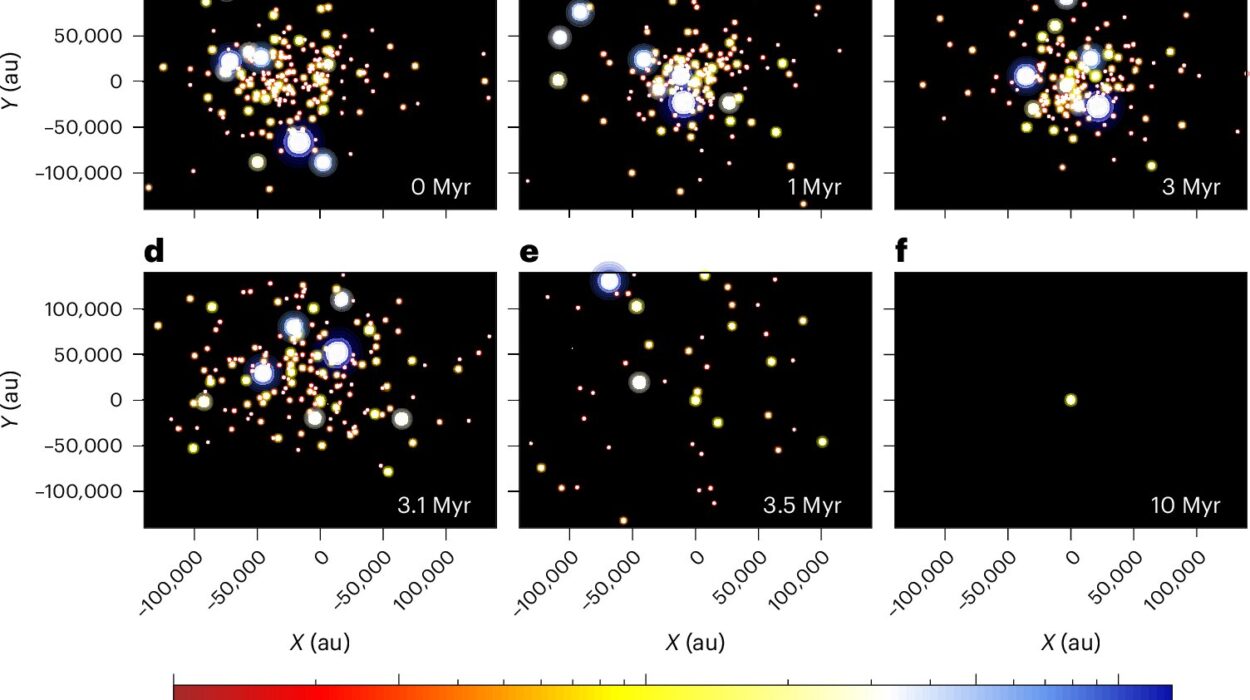

The star is also relatively young by cosmic standards—about 2 billion years old. For comparison, the Sun is more than twice as old. Despite its youth, TOI-2431 has already watched TOI-2431 b inch slowly closer with every orbit. This inward spiral, known as tidal decay, may eventually spell the planet’s end.

Astronomers have calculated that the planet’s tidal decay timescale is only 31 million years—a blink in the lifetime of a star. After that, TOI-2431 b may be torn apart or swallowed entirely. It’s a reminder that even planetary systems are not static. They change, evolve, and sometimes collapse under the weight of their own gravity.

Peering Deeper with the James Webb Space Telescope

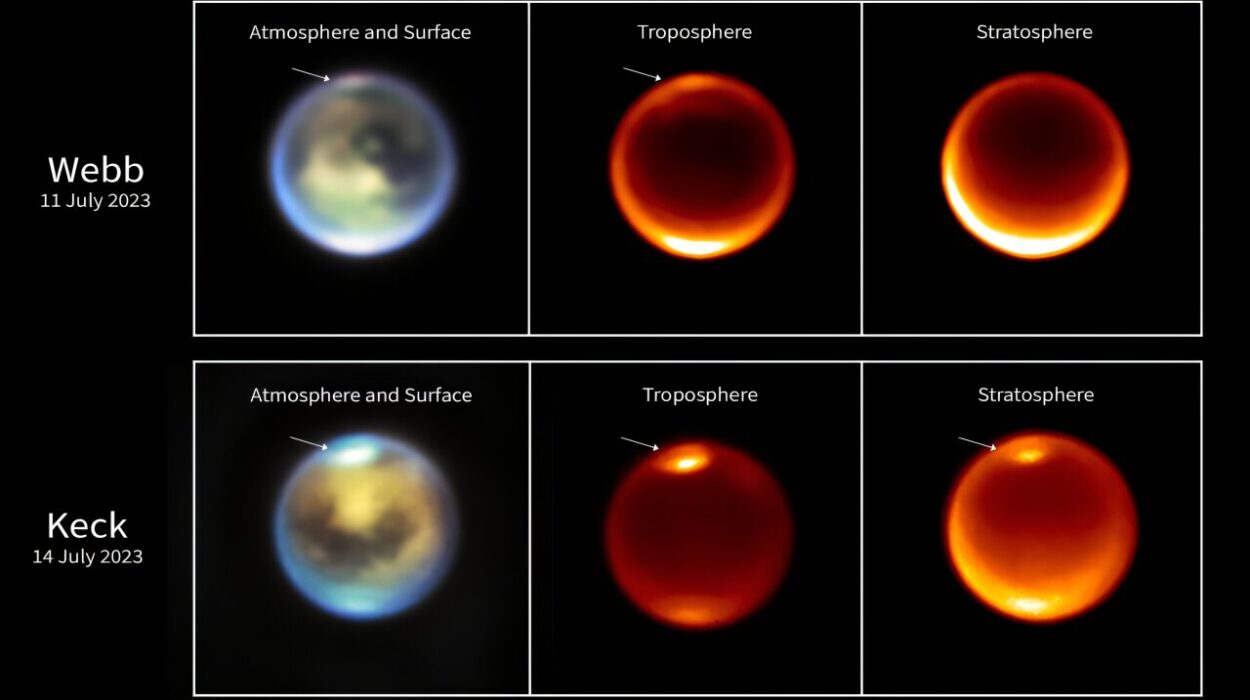

What makes TOI-2431 b so fascinating isn’t just its extremity—it’s that it might teach us what extreme planets are made of. Because of its short orbit and high temperature, it’s a perfect candidate for phase curve observations using the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST). These observations can help detect heat variations across the planet’s surface, chemical signatures in its atmosphere (if any), and potentially even volcanic activity.

One burning question: does TOI-2431 b have an atmosphere? If it does, it must be constantly blasted by solar winds and stripped by radiation. But if remnants remain—perhaps clinging to the planet’s night side—they could hold clues about how atmospheres form and survive on extreme worlds. The JWST, with its unmatched sensitivity, may be able to detect such whispers in the dark.

And even if no atmosphere is found, TOI-2431 b remains invaluable. Its mass, size, temperature, and orbit provide a natural laboratory for studying rocky planet evolution, tidal physics, and the limits of planetary endurance. In some ways, it’s like a distant echo of Mercury, but taken to a brutal extreme.

A Reminder of Cosmic Diversity

The discovery of TOI-2431 b is another note in the growing symphony of alien worlds TESS and other missions have revealed. Since TESS began its mission in 2018, it has identified over 7,600 potential exoplanets. Of these, 638 have been confirmed, and each tells a different story.

Some orbit stars in habitable zones. Others are gas giants larger than Jupiter. Some are frozen. Some are volcanic. TOI-2431 b reminds us that some planets live fast and die young, orbiting so close to their stars that they burn almost from birth.

Yet each new world expands our understanding—not just of planets, but of how solar systems form and behave. In studying the strange, we learn more about the familiar.

One Tiny Flicker, One Giant Leap for Curiosity

The flicker that first hinted at TOI-2431 b’s presence lasted just a few hours. But from that blink of light came a chain of investigation, discovery, and awe that spanned the globe—and eventually, the stars.

It is humbling to think how much we can now learn from a single dip in brightness, how we can deduce the shape of a distant world, the tug of its tides, the scorch of its sun, and the countdown to its demise—all from the comfort of Earth.

As our tools grow more powerful, and as missions like TESS and JWST continue their vigil, we may soon uncover thousands more planets like TOI-2431 b. Each one will have its own orbit, its own climate, its own story.

And perhaps, one day, one of those stories will include life.

Until then, we listen for the flickers, we measure the shadows, and we marvel at the secrets they whisper from across the void.

Reference: Kaya Han Taş et al, An Earth-Sized Planet in a 5.4h Orbit Around a Nearby K dwarf, arXiv (2025). DOI: 10.48550/arxiv.2507.08464