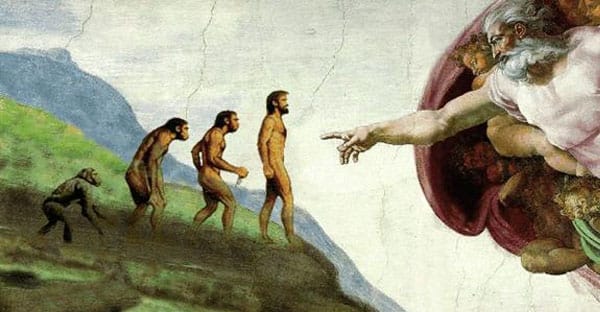

For centuries, humans have drawn a line between ourselves and the rest of the animal kingdom. We’ve prided ourselves on our capacity to think rationally—to weigh evidence, revise our beliefs, and adapt to new information. But what if that ability isn’t uniquely human after all? A groundbreaking new study suggests it’s not.

Published in the prestigious journal Science, the study titled “Chimpanzees rationally revise their beliefs” reveals that our closest evolutionary relatives can change their minds when presented with better evidence—a hallmark of rational thought. Conducted by an international team of researchers, including UC Berkeley psychologists Emily Sanford and Jan Engelmann and Utrecht University’s Hanna Schleihauf, the work challenges long-held assumptions about the cognitive gulf separating humans from other primates.

A Window Into the Primate Mind

The research took place at the Ngamba Island Chimpanzee Sanctuary in Uganda, home to dozens of rescued chimpanzees living in a semi-natural environment. The scientists designed an experiment that tested not instinct or memory, but reasoning—specifically, the ability to update beliefs when new information comes to light.

In the experiment, each chimpanzee faced two boxes, one of which contained a hidden food reward. At first, the animals received a clue pointing toward one box. Later, they were given a stronger, more reliable clue suggesting the food might actually be in the other box.

The chimps’ responses were striking. Rather than stubbornly sticking to their first choice, many of them changed their selection when the new evidence appeared more convincing. This wasn’t a random or impulsive switch—it reflected a deliberate re-evaluation of what they believed to be true.

“Chimpanzees were able to revise their beliefs when better evidence became available,” explained Emily Sanford, a postdoctoral researcher in UC Berkeley’s Social Origins Lab. “This kind of flexible reasoning is something we often associate with 4-year-old children. It was exciting to show that chimps can do this too.”

Thinking Beyond Instinct

One of the major challenges in animal cognition research is distinguishing genuine reasoning from simple behavioral patterns. Were the chimps truly evaluating the strength of the evidence, or were they merely reacting to the most recent or most obvious clue?

To answer that, the team introduced rigorous controls and computational modeling. These models allowed them to simulate different cognitive strategies—such as “recency bias,” where animals might favor the last clue they received, or “stimulus bias,” where they might respond to whichever signal seemed most salient.

The results were clear: the chimpanzees’ behavior best matched models based on rational belief revision, not simple reflexes or habits.

“We recorded their first choice, then their second, and compared whether they revised their beliefs,” Sanford said. “We also used computational models to test how their choices matched up with various reasoning strategies.”

What emerged was a picture of intelligent, flexible decision-making—an ability to assess the quality of information and adjust accordingly. In other words, the chimps were doing something we once thought only humans could do: they were thinking about their thinking.

Rethinking Rationality

For decades, scientists assumed that rational reasoning—forming beliefs based on evidence and updating them as new data arrives—was an intellectual frontier that belonged solely to humans. But this study, Sanford notes, suggests otherwise.

“The difference between humans and chimpanzees isn’t a categorical leap. It’s more like a continuum,” she explained.

That continuum stretches across millions of years of shared evolutionary history. Humans and chimpanzees share roughly 98 percent of their DNA, and both species rely on complex social systems, emotional intelligence, and learning from others. The discovery that chimpanzees can also engage in rational belief revision adds another profound similarity to the list.

This research doesn’t just close the cognitive gap—it challenges how we define what it means to be rational. Rationality may not be a human invention, but an evolved trait—one that helped both species survive in dynamic, unpredictable environments where flexibility of thought could mean the difference between life and death.

Lessons for Learning, AI, and Beyond

Sanford believes these findings reach far beyond the chimpanzee sanctuary. Understanding how primates process and update information can reshape the way scientists think about learning, child development, and even artificial intelligence.

“This research can help us think differently about how we approach early education or how we model reasoning in AI systems,” she said. “We shouldn’t assume children are blank slates when they walk into a classroom.”

The ability to revise beliefs isn’t just about intelligence—it’s about adaptability. In humans, it underpins critical thinking, scientific progress, and even emotional maturity. In artificial intelligence, it’s the foundation for systems that can learn autonomously and correct their own mistakes.

By exploring how chimpanzees reason, scientists can uncover the building blocks of rationality itself—the evolutionary blueprint for flexible thought that stretches from the jungle to the digital age.

From Chimps to Children: The Next Step

The next phase of Sanford’s work brings the same experimental design to human children. Her team is currently testing toddlers aged two to four to compare how young humans and chimpanzees revise their beliefs when faced with conflicting evidence.

“It’s fascinating to design a task for chimps, and then try to adapt it for a toddler,” she said. “Both are incredibly curious, but they process information in subtly different ways.”

These comparisons could reveal how reasoning evolves in early childhood—and how much of it is shared with our primate cousins. If toddlers and chimps display similar patterns of belief revision, it would suggest that the roots of human rationality are far older than our species itself.

Eventually, Sanford hopes to extend this work to other primates—bonobos, orangutans, and gorillas—to create a comprehensive map of reasoning abilities across evolutionary branches. Such a comparative approach could answer fundamental questions: How unique is human thought? And how far back does the spark of rational intelligence truly go?

Beyond Assumptions: The Intelligence of Animals

Sanford’s research is part of a broader shift in how scientists view animal intelligence. For centuries, humans underestimated the cognitive sophistication of other species. Yet evidence continues to mount that animals—from dolphins and crows to octopuses and dogs—exhibit forms of reasoning, communication, and even empathy that blur the line between instinct and intellect.

“They may not know what science is,” Sanford said, “but they’re navigating complex environments with intelligent and adaptive strategies. And that’s something worth paying attention to.”

This humility is central to modern cognitive science. The more researchers learn, the more they realize that intelligence doesn’t follow a single path—it evolves wherever it’s needed. For chimpanzees, rational flexibility might help them find food, solve social conflicts, or interpret subtle signals from their group. For humans, it’s what allows us to build civilizations, conduct experiments, and write stories about the minds of others.

The Broader Meaning of Changing One’s Mind

At its heart, this study is about something deeply human: the courage to change one’s mind. We live in a world where beliefs—political, cultural, personal—often feel immovable. Yet the ability to revise those beliefs, to let new evidence reshape our understanding, is what drives growth and progress.

If chimpanzees share even a spark of that ability, it means that the roots of open-mindedness stretch far beyond humanity. It means that rational thought isn’t a cultural artifact—it’s a natural instinct, woven into the very fabric of intelligent life.

The image of a chimp sitting before two boxes, hesitating, considering, and then changing its choice might seem simple. But within that moment lies something profound: a mind reflecting on itself, re-evaluating what it knows, and daring to think differently.

The Continuum of Thought

Sanford’s work reminds us that rationality is not a summit humans alone have reached—it’s a continuum we share with our evolutionary relatives. From the forest canopies of Uganda to the laboratories of UC Berkeley, minds across species are engaged in the same ancient dance: gathering evidence, weighing it, and choosing what to believe.

It’s a dance that has defined intelligence since life began seeking order in a chaotic world. And as we learn more about how other beings think, we may discover that the essence of wisdom—the ability to listen to reason, even when it contradicts what we once believed—isn’t just human after all.

In the quiet reasoning of a chimpanzee lies a reflection of ourselves: thoughtful, curious, and capable of change.

More information: Hanna Schleihauf et al, Chimpanzees rationally revise their beliefs, Science (2025). DOI: 10.1126/science.adq5229. www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.adq5229