High in the Andes Mountains of present-day Peru, at more than 3,400 meters (11,200 feet) above sea level, lies the ancient city of Cusco. Once the capital of the Inca Empire—the largest empire ever to exist in the Americas—Cusco was more than just a city. It was the beating heart of a civilization that ruled vast stretches of South America, a sacred place where power, religion, and culture converged. To walk through Cusco today is to walk through history, where Spanish colonial architecture rises on the foundations of Inca stonework, and where traditions rooted in the empire still live in the rhythm of the streets.

To understand Cusco is to understand the Incas, a people who, in less than a century, built an empire stretching from modern-day Colombia to Chile. Their capital was not only the administrative center but also the symbolic navel of their world. The Incas called it Qosqo—the center, the place where the universe converged. To them, Cusco was more than a city; it was the cosmos materialized in stone.

Origins and Mythical Foundations

The story of Cusco begins in both myth and history. According to Inca legend, the city was founded by Manco Cápac and Mama Ocllo, children of the sun god Inti, who emerged from Lake Titicaca to bring civilization to humankind. Guided by their divine mission, they traveled until the golden staff they carried sank into the ground, marking the sacred site where Cusco would rise.

Another version of the myth tells of four brothers and four sisters—the Ayar siblings—who set out from a cave called Pacaritambo. After many trials, only Manco Cápac and his kin reached the valley where Cusco now stands. Both myths emphasize divine origin, legitimacy, and destiny: Cusco was not chosen by chance but by the gods themselves.

Archaeological evidence suggests that the Cusco valley was inhabited long before the Incas rose to power. Small agricultural communities thrived there as early as 1,000 years before the Inca Empire, benefiting from fertile soils and access to water. But it was around the 13th century that the Incas, a relatively small ethnic group at the time, established Cusco as their political and ceremonial center.

The Transformation into Imperial Capital

When the Incas began consolidating power under their early rulers, Cusco was a modest settlement. Its transformation into the dazzling imperial capital is credited largely to Pachacuti Inca Yupanqui, the ninth Sapa Inca (emperor), who reigned in the mid-15th century. Pachacuti was not only a brilliant military strategist but also a visionary city planner.

He redesigned Cusco into the shape of a puma, a sacred animal representing power and protection. The head of the puma was Sacsayhuamán, the colossal fortress overlooking the city. The body was formed by the central districts, and the tail extended toward the confluence of rivers. This symbolic design fused cosmology and politics, embedding meaning into every stone.

Under Pachacuti and his successors, Cusco became the center of an empire that stretched thousands of kilometers. The city’s palaces, temples, and plazas embodied Inca ideals of order, harmony, and sacred geometry. The empire’s vast road system, the Qhapaq Ñan, radiated outward from Cusco like arteries from a heart, binding together diverse peoples and landscapes under the rule of the Sapa Inca.

The Sacred Geography of Cusco

For the Incas, Cusco was not simply a capital of government but also a sacred geography. They believed it was the “navel of the world,” where the three realms of existence met: Hanan Pacha (the upper world of gods and stars), Kay Pacha (the earthly realm of living beings), and Ukhu Pacha (the underworld of ancestors and the dead).

Radiating out from Cusco were ceques—sacred lines that connected hundreds of shrines, or huacas, scattered across the landscape. These ceques structured ritual life, agricultural cycles, and political organization, ensuring that Cusco was the spiritual center of a cosmic web.

The city itself was divided into two halves: Hanan Cusco (upper Cusco) and Hurin Cusco (lower Cusco). This division reflected the Inca concept of duality—opposites in balance, like day and night, male and female, sky and earth. Every palace, temple, and district was woven into this cosmic order, reinforcing the Incas’ vision of harmony between humans, nature, and the divine.

Architecture of Stone and Spirit

Perhaps the most striking legacy of Cusco is its architecture. The Incas mastered the art of stone construction in ways that continue to astonish modern engineers. Without iron tools, wheels, or mortar, they carved and fitted massive stones with such precision that not even a blade of grass could slip between them. These walls were not only durable—resisting earthquakes that toppled colonial structures centuries later—but also imbued with meaning.

At the heart of Cusco stood the Qorikancha, or Temple of the Sun, the most important religious site in the empire. Its walls, once sheathed in sheets of gold, honored Inti, the sun god, and housed shrines to the moon, stars, and thunder. The temple was both astronomical observatory and ritual center, aligning with solstices and celestial events that guided agricultural and ceremonial calendars.

Nearby stood the Sacsayhuamán fortress, an awe-inspiring complex of zigzagging stone walls that formed the puma’s head. Built with stones weighing up to 200 tons, transported and fitted with unmatched skill, Sacsayhuamán was both defensive stronghold and ceremonial stage, where massive festivals celebrated the power of the empire and the cyclical renewal of the cosmos.

The palaces of Cusco, belonging to different emperors, reflected both power and continuity. Each ruler built his palace during his lifetime, but upon his death, the palace was preserved for his mummified body and lineage, while his successor had to construct a new residence. This practice turned Cusco into a city of ancestral memory, where the living and the dead coexisted.

Life in the Imperial Capital

Life in Cusco was a blend of ritual, administration, and cultural exchange. As the empire’s capital, it attracted people from across the Andes—administrators, artisans, priests, soldiers, and laborers. The city’s population swelled with representatives of conquered peoples, who brought with them traditions, goods, and skills, enriching the cultural mosaic.

At the center of daily life was the main square, Haukaypata, where ceremonies, markets, and imperial proclamations took place. Religious festivals filled the calendar, the most famous being Inti Raymi, the Festival of the Sun, which celebrated the winter solstice with elaborate rituals, dances, and offerings to ensure the return of the sun and the fertility of the land.

Agriculture sustained Cusco and the empire. Terraces carved into mountain slopes maximized farmland, while irrigation systems harnessed water from rivers and springs. The fertile Sacred Valley, not far from Cusco, served as the breadbasket of the empire, providing maize, potatoes, and quinoa to feed the city’s elite and support ceremonial offerings.

In Cusco, religion was inseparable from governance. The Sapa Inca was both political ruler and divine figure, considered a descendant of the sun god. His presence in the city symbolized the union of heaven and earth, while rituals conducted in temples and plazas reinforced his legitimacy.

The Fall of Cusco

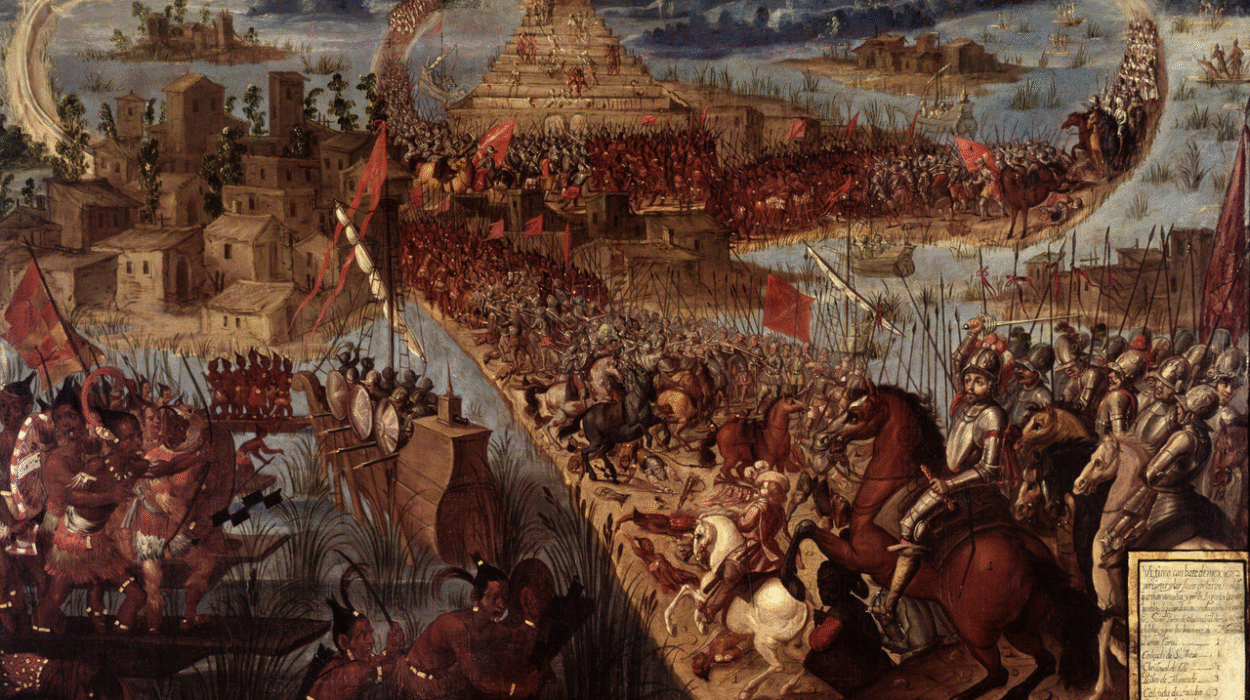

The glory of Cusco was not to last. In 1533, after a series of brutal battles, Spanish conquistadors led by Francisco Pizarro captured the city. They were aided by internal divisions within the empire, particularly the civil war between the brothers Atahualpa and Huáscar, who had contested the throne.

The Spaniards looted Cusco, stripping the Qorikancha of its gold and silver. Temples were destroyed or converted into churches, and colonial buildings were erected on Inca foundations. Yet, even in conquest, the resilience of Inca architecture endured: the stone walls remained, supporting structures that told of both continuity and rupture.

The Spanish attempted to suppress Inca traditions, but the spirit of Cusco persisted. Festivals such as Inti Raymi were banned, yet rituals survived in disguised forms, blending with Catholic celebrations. The city became a symbol of cultural resistance, where Andean identity endured beneath colonial rule.

Cusco in the Modern World

Today, Cusco is a UNESCO World Heritage Site and one of the most visited destinations in South America. Tourists flock to its cobblestone streets, marvel at the seamless Inca walls, and use the city as a gateway to Machu Picchu. Yet Cusco is more than a tourist attraction; it remains a living city where Andean traditions are celebrated and reinterpreted.

Each June, thousands gather for the modern revival of Inti Raymi, staged at Sacsayhuamán. Though partly theatrical, the festival reflects a genuine desire to reconnect with ancestral heritage and honor the cosmology that once defined the Inca world.

The blend of Inca and Spanish architecture gives Cusco its unique character. The Cathedral of Santo Domingo rises over the ruins of the Qorikancha, a vivid symbol of cultural collision. Streets lined with colonial balconies still rest on massive Inca walls, a daily reminder of the city’s layered history.

Cusco also faces challenges. Tourism brings economic opportunity but also strains infrastructure and raises questions about preservation. Balancing the needs of a modern city with the responsibility of safeguarding its heritage is a delicate task. Yet Cusco’s resilience—like the stones that survived earthquakes and conquest—suggests it will continue to endure.

The Legacy of Cusco

Cusco’s legacy extends far beyond Peru. It represents the ingenuity, resilience, and spiritual depth of the Inca civilization. It is a reminder that cities are not merely places to live but expressions of cultural identity, belief, and power.

For the Incas, Cusco was the center of the universe, a place where gods, ancestors, and living beings converged. For the modern world, it is a testament to the heights of human creativity, a city that withstood conquest and colonization yet retained its soul.

When one stands in the Plaza de Armas, gazing at the cathedral built on Inca foundations, or touches the ancient stones of Sacsayhuamán, there is a palpable sense of continuity. Time collapses, and the echoes of drums, chants, and footsteps of the past still linger in the Andean air.

Conclusion: A City Beyond Time

Cusco is not just a city of the past—it is a city of the present and the future. Its story is one of transformation, resilience, and cultural fusion. It was born of myth, shaped by emperors, scarred by conquest, and reborn as a symbol of heritage.

To ask what Cusco is, is to ask what it means for a city to embody the soul of a people. It is to recognize that Cusco, once the capital of the Inca Empire, continues to live as a sacred heart of the Andes, where the stones whisper of empires, gods, and human endurance.

In the end, Cusco teaches us that civilizations rise and fall, but their spirit can live on in the places they build. The Inca may no longer rule, but in Cusco, their presence is eternal—etched into every stone, every festival, and every story passed from generation to generation. The city remains, as it always was, the center of the world.