In the heart of the Valley of Mexico, where high mountains circle a basin dotted with lakes, a city once shimmered on the water like a vision. Its palaces gleamed with white stucco, its marketplaces roared with the voices of tens of thousands of traders, and its causeways stretched out like the arms of a giant, connecting an island city to the mainland. This was Tenochtitlán—the great Aztec capital, the crown jewel of Mesoamerica, and one of the most extraordinary cities the world has ever seen.

For the Mexica, the people we now call the Aztecs, Tenochtitlán was more than just a political center. It was a sacred place, a city prophesied by their gods and born from struggle and resilience. To the Spaniards who encountered it in the 16th century, it seemed like something from a dream, a city as grand as any in Europe, yet unlike anything they had ever imagined.

Tenochtitlán’s story is one of vision and ingenuity, but also of empire, conquest, and eventual tragedy. To understand it is to explore not just a city, but a civilization—its myths, its architecture, its economy, and its people, who turned an island in a swamp into the beating heart of a mighty empire.

The Mythic Origins

The history of Tenochtitlán begins not with stone and mortar, but with myth. The Mexica people, according to their traditions, were once nomads wandering in search of a home promised to them by their god Huitzilopochtli, the patron of the sun and war. He gave them a prophecy: they would find their destined city where an eagle perched on a cactus devoured a snake.

Their journey was long and harsh, filled with rejection by other peoples of the Valley of Mexico. But eventually, around 1325, they came to a small island in the middle of Lake Texcoco. There, among reeds and water, they saw the vision—the eagle, the cactus, the serpent. It was an unlikely place to build a city, surrounded by marshes and unstable ground. Yet the Mexica believed it was divine will, and they began to construct their capital.

The symbol of the eagle on the cactus lives on even today, emblazoned at the center of Mexico’s national flag. It is a reminder that from the humblest and harshest beginnings can rise something magnificent.

The Growth of an Island Empire

At first, Tenochtitlán was small, a cluster of houses and temples built on a swampy island. Survival required ingenuity. The Mexica developed chinampas, or floating gardens—rectangular plots built from mud, reeds, and vegetation that extended the land into the shallow waters of the lake. These fertile artificial islands produced abundant crops of maize, beans, squash, and chili peppers, feeding a growing population.

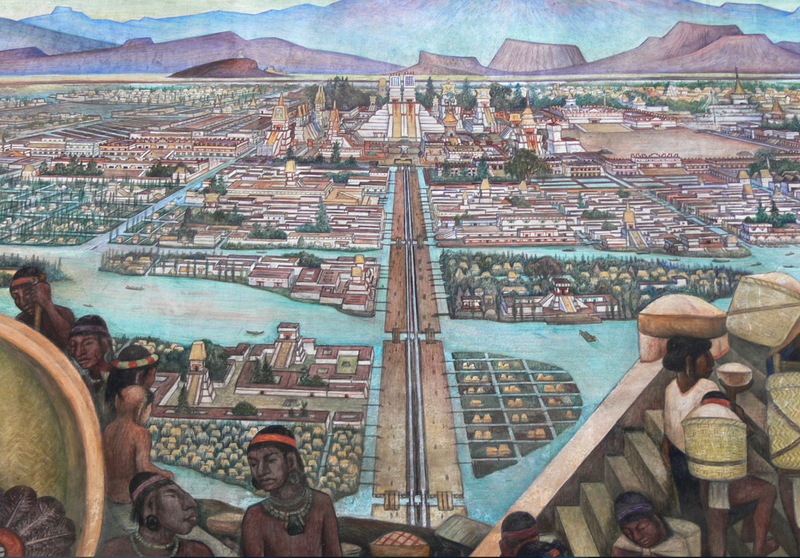

Over the next two centuries, Tenochtitlán expanded dramatically. Canals and causeways transformed the city into a hub of movement and trade, where canoes glided like Venetian gondolas and bustling causeways brought goods and people from distant regions. Aqueducts carried fresh water from springs in the mountains, while dikes and levees controlled flooding and separated fresh and brackish water.

Through alliances and conquests, the Mexica established the Triple Alliance—a union with the city-states of Texcoco and Tlacopan—that would form the backbone of the Aztec Empire. Tenochtitlán, as the most powerful of the three, quickly became the dominant political, economic, and military force in Mesoamerica. By the early 16th century, the city may have housed 200,000 to 250,000 people, making it one of the largest cities in the world at the time, rivaling European capitals like Paris and Constantinople.

The Splendor of the City

To imagine Tenochtitlán is to picture a city unlike any other. Spanish chroniclers, upon entering the city in 1519, struggled to describe what they saw. Bernal Díaz del Castillo, one of Hernán Cortés’s men, recalled that it seemed like something out of a dream, with wide streets, bustling markets, and palaces so grand they seemed impossible to conquer.

The city was divided into four main districts, each subdivided into neighborhoods known as calpulli. Its streets were organized with remarkable order, crisscrossed by canals that functioned like watery highways. Canoes carried people and goods, while stone causeways with drawbridges allowed armies and merchants to cross the lake.

At the city’s center rose the Templo Mayor, or Great Temple, a massive pyramid with twin shrines dedicated to Huitzilopochtli, god of war and the sun, and Tlaloc, god of rain and fertility. This was the spiritual heart of the city, where rituals, festivals, and offerings—sometimes including human sacrifices—were made to ensure the balance of the cosmos. Surrounding it were palaces, administrative buildings, schools, and ball courts.

The city was alive with color and sound. Marketplaces such as Tlatelolco overflowed with merchants selling everything from obsidian blades to tropical fruits, jaguar pelts, cacao beans, jewelry, and vibrant feathers of exotic birds. Thousands of people traded daily, governed by laws and overseen by officials who ensured fair practice. This thriving economy connected Tenochtitlán to regions across Mesoamerica, making it a true center of commerce.

Society and Culture

Tenochtitlán was not just stone and water—it was people. Its society was highly structured, with a clear hierarchy. At the top stood the tlatoani, the ruler, whose authority extended not only over the city but over the entire empire. Beneath him were nobles, priests, warriors, and administrators, while artisans, farmers, merchants, and laborers formed the backbone of everyday life.

Education was valued. Children, regardless of social class, attended schools where they learned history, religion, and practical skills. The calmecac trained future priests and leaders, while the telpochcalli prepared commoner boys for military and civic duties. Women played essential roles, managing households, weaving textiles, and participating in trade.

Religion permeated every aspect of life. The Mexica believed their gods required nourishment, and rituals ensured the sun would rise, the rains would fall, and the world would continue. Festivals filled the calendar, and while human sacrifice was a dramatic and often misunderstood practice, it was only one part of a complex spiritual system that sought balance between humans, gods, and the cosmos.

Art and architecture flourished in Tenochtitlán. Sculptures, codices (painted books), and murals depicted gods, rituals, and histories. Music, poetry, and dance were integral to celebrations and ceremonies, enriching the cultural life of the city.

The Fall of Tenochtitlán

For all its grandeur, Tenochtitlán’s greatness was destined to collide with forces beyond its imagination. In 1519, Hernán Cortés and his band of Spanish conquistadors marched into the Valley of Mexico, drawn by rumors of a wealthy empire. Initially, the Mexica ruler Montezuma II welcomed them into the city, perhaps seeing them as potential allies—or even as divine figures.

But tensions quickly escalated. The Spaniards allied with enemies of the Mexica, most notably the Tlaxcalans, and exploited divisions within the empire. Violence erupted, and in 1521, after months of brutal siege, famine, and disease, the Spaniards and their allies captured and destroyed Tenochtitlán.

The fall of the city was catastrophic. The once-great capital was reduced to rubble, its canals filled, its temples torn down. On its ruins, the Spanish built Mexico City, the capital of New Spain and later of independent Mexico. Yet beneath the colonial city, remnants of Tenochtitlán remained, and today archaeologists continue to uncover its foundations, bringing its story back to light.

The Legacy of Tenochtitlán

Though Tenochtitlán fell, its legacy endures. It is remembered not only as a city of stone but as a symbol of resilience, ingenuity, and cultural achievement. The Mexica transformed an inhospitable island into one of the greatest cities in the world, and their innovations in agriculture, engineering, and governance still inspire awe.

The myths of its founding continue to shape Mexican identity, while its ruins remind us of both human creativity and the fragility of civilizations. The Templo Mayor has been excavated in modern Mexico City, offering a window into the sacred heart of the Aztec world. Codices, artifacts, and oral traditions preserve glimpses of the life, beliefs, and artistry of the people who once walked its streets.

Tenochtitlán also serves as a reminder of the encounter between worlds—the meeting of Europe and the Americas, which brought exchange, conflict, and transformation. Its story is one of triumph and tragedy, resilience and loss, but also of continuity, for the descendants of the Mexica live on, carrying forward traditions that link past to present.

Conclusion: The City of Dreams and Echoes

Tenochtitlán was more than a capital; it was a masterpiece of human vision, born from myth and built with ingenuity. Rising from the waters of Lake Texcoco, it became a city of canals and temples, markets and palaces, warriors and poets. It dazzled those who saw it and still captures the imagination centuries after its fall.

Though destroyed, Tenochtitlán was never erased. It lives on in the stones beneath Mexico City, in the art and stories of its people, and in the very identity of a nation. To speak of Tenochtitlán is to speak of human creativity at its height, of the beauty and fragility of civilizations, and of the enduring power of memory.

In the end, Tenochtitlán was a city of both dreams and echoes—a place where gods and humans met, where empires rose and fell, and where the story of a people continues to shape the world.