Throughout human history, certain civilizations have left legacies so profound that they continue to shape the way we live today. Ancient China is one of those civilizations. From the fertile lands of the Yellow River valley to the bustling trade routes of the Silk Road, China was not only a cultural and political giant but also a cradle of ingenuity. It was in this ancient land that some of the most transformative inventions in human history were born—ideas and creations that spread across continents, altering economies, warfare, communication, science, and everyday life.

When we think of invention, we often imagine solitary genius, a single figure struck by a sudden flash of insight. But in reality, inventions emerge from the needs and challenges of societies. In ancient China, a vast and diverse population, frequent warfare, expanding trade, and philosophical curiosity all fueled innovation. The Chinese approach to invention was often practical: finding solutions to immediate problems, whether in agriculture, governance, or survival. Yet many of these solutions transcended their original purpose, becoming global milestones of progress.

To explore the story of ancient Chinese inventions is to embark on a journey through time, witnessing how human creativity reshaped the course of civilizations. These inventions were not isolated achievements—they were threads woven into the broader fabric of world history, connecting East and West, past and present.

The Invention of Paper: The Voice of Civilization

Few inventions have altered human civilization as dramatically as paper. Before its arrival, people wrote on bamboo slips, silk, or other cumbersome materials. Bamboo was heavy and awkward; silk was exquisite but expensive. What society needed was something light, cheap, and accessible.

In the Eastern Han Dynasty around 105 CE, a court official named Cai Lun is credited with refining the papermaking process. Using bark, hemp, rags, and fishing nets, he created a pulp that could be spread, pressed, and dried into sheets. This invention revolutionized communication and record-keeping. Suddenly, knowledge could be preserved more easily and shared more widely.

The impact of paper was profound. It facilitated the spread of literature, science, philosophy, and government records across China. Confucian texts could be copied more efficiently, examinations for government officials became more widespread, and education became accessible to more than just the elite.

Eventually, the secret of papermaking spread beyond China, traveling along the Silk Road to the Islamic world and later to Europe. By the time Gutenberg invented the printing press in the 15th century, paper had already laid the foundation for the explosion of literacy and the preservation of knowledge. Without paper, the Renaissance, the Enlightenment, and the modern age would have been unthinkable.

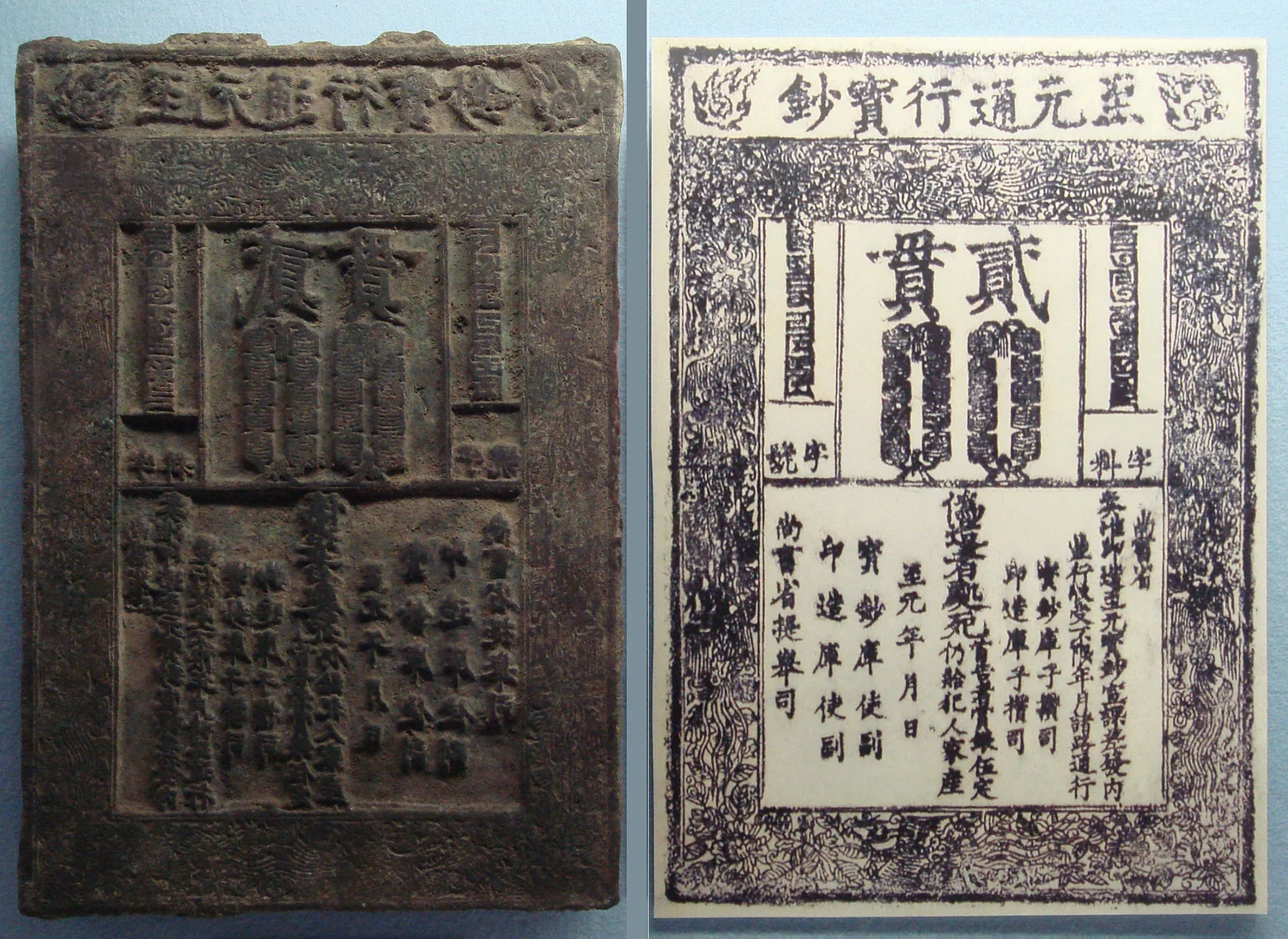

Printing: The Democratization of Knowledge

If paper gave humanity a medium, printing gave it power. The ability to replicate texts quickly and accurately transformed how knowledge was stored and shared. In China, this revolution began centuries before Gutenberg.

During the Tang Dynasty in the 7th century, woodblock printing emerged. Artisans carved entire pages of text and illustrations into wooden blocks, inked them, and pressed them onto paper. This method allowed for mass production of books, religious texts, and calendars. One of the earliest and most famous examples is the Diamond Sutra, printed in 868 CE, the world’s oldest surviving printed book.

By the 11th century, Bi Sheng introduced movable type printing, creating characters on clay pieces that could be rearranged and reused. Though the system faced challenges due to the sheer number of Chinese characters, the principle it introduced was revolutionary. Centuries later, movable type would be reinvented in Europe and fuel an intellectual revolution.

Printing in China not only spread literacy but also safeguarded culture. Historical records, scientific works, medical knowledge, and poetry were no longer vulnerable to being lost in fires or wars. Ideas became durable, portable, and shareable—shaping the intellectual landscape of the world.

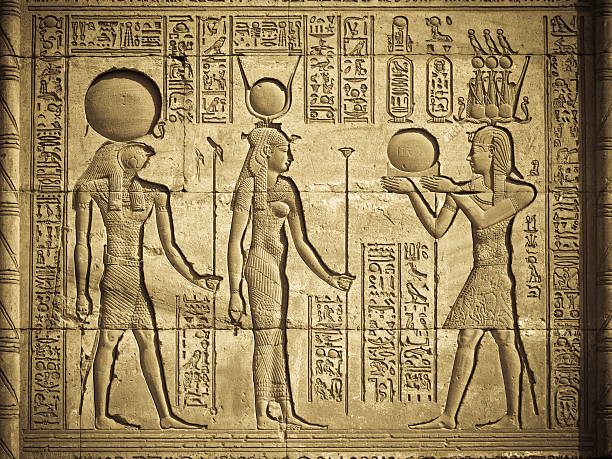

The Compass: Guiding Civilizations

Long before GPS or even magnetic compasses on ships, ancient Chinese scholars were experimenting with the mysterious force of magnetism. By the Han Dynasty, they discovered that a lodestone, a naturally magnetized rock, could align itself with the Earth’s magnetic field. This curiosity became a tool with profound consequences.

Originally, the compass was not used for navigation but for divination and geomancy—particularly in Feng Shui, to determine the harmony of buildings with the cosmos. Over time, however, its potential for navigation became clear. By the Song Dynasty (11th century), sailors were using magnetic compasses at sea, allowing them to navigate even on cloudy days when stars were hidden.

The compass transformed exploration and trade. It enabled Chinese ships to sail farther with confidence, strengthening maritime trade routes across the Indian Ocean and beyond. When the technology spread to the Islamic world and later Europe, it helped launch the Age of Exploration, leading to voyages that would connect the entire globe.

In many ways, the compass symbolizes humanity’s eternal desire to explore and understand its place in the world. With this tool, horizons expanded, cultures encountered one another, and history was forever altered.

Gunpowder: The Alchemy of Destruction and Innovation

Few inventions have carried consequences as dramatic and double-edged as gunpowder. It was discovered in China not as a weapon, but as an alchemical pursuit. Taoist alchemists of the Tang Dynasty, searching for the elixir of immortality, stumbled upon a volatile mixture of sulfur, charcoal, and saltpeter. Instead of eternal life, they discovered explosive fire.

By the 9th century, gunpowder was used in fireworks, adding spectacle to festivals and rituals. But its military potential could not be ignored. By the Song Dynasty, gunpowder weapons emerged: fire arrows, bombs, flamethrowers, and eventually cannons.

When gunpowder knowledge spread westward, it altered the course of global history. Castles fell to cannons, knights gave way to musketeers, and warfare entered a new era. Entire empires rose and fell on the power of gunpowder.

Yet gunpowder also had constructive uses. Fireworks became an art form, symbolizing celebration and joy across cultures. Mining, engineering, and construction benefited from controlled explosions. The invention that began as an accident of alchemy became both a destructive force and a tool of creation.

Silk: The Fabric of Civilization

Though not a single invention, silk was an innovation so significant that it shaped economies and connected continents. According to legend, Empress Leizu discovered silk around 2700 BCE when a silkworm’s cocoon fell into her tea, unraveling into fine threads. This delicate fiber became one of China’s greatest treasures.

Silk was prized for its beauty, strength, and versatility. For centuries, its production was a closely guarded secret, punishable by death if revealed to outsiders. Silk garments became symbols of status and refinement, while silk itself became the foundation of international trade.

The Silk Road, named after this precious material, was more than a trade route—it was a bridge between East and West, carrying not only goods but also ideas, technologies, and cultures. From Rome to Persia to India, silk became synonymous with luxury, diplomacy, and cultural exchange.

The invention of sericulture—the cultivation of silkworms and production of silk—was not just about textiles. It was about global connection, economic power, and cultural influence. Few materials in history have carried such weight in shaping civilizations.

The Seismograph: Listening to the Earth

Among the less celebrated but equally remarkable Chinese inventions is the seismograph, created by Zhang Heng in 132 CE during the Han Dynasty. This ingenious device was designed to detect distant earthquakes, a vital tool for a vast empire where natural disasters could devastate communities.

Zhang’s seismograph consisted of a bronze vessel with dragon heads pointing in eight directions. Each dragon held a ball in its mouth, which would fall into the mouth of a toad below when an earthquake occurred. The direction of the falling ball indicated the direction of the tremor’s origin.

Though rudimentary compared to modern instruments, this invention revealed an extraordinary understanding of natural forces and engineering. It demonstrated that humans could not only observe but also measure and interpret the invisible movements of the Earth.

The seismograph embodies the Chinese tradition of blending science with practicality, turning curiosity about nature into tools for governance and survival.

Agricultural Innovations: Feeding the Empire

For any civilization, food security is the foundation of prosperity. Ancient China, with its vast population, needed agricultural innovation to sustain itself. The Chinese responded with ingenuity that changed farming forever.

One of the most significant innovations was the development of iron tools and plows, which increased efficiency and allowed cultivation of tougher soils. The invention of the seed drill during the Han Dynasty ensured that seeds were planted evenly and at the right depth, improving crop yields.

Irrigation systems, including canals, waterwheels, and chain pumps, transformed dry lands into fertile fields. Rice cultivation in southern China, with its intricate paddy systems, supported booming populations.

These agricultural inventions not only fed millions but also freed labor for other pursuits, enabling cultural, political, and technological advancements. They highlight how Chinese innovation was deeply rooted in the needs of everyday life.

The Mechanical Clock: Measuring Time with Precision

Timekeeping has always been essential to human societies, and in ancient China, it reached remarkable sophistication. During the Tang Dynasty, Yi Xing, a Buddhist monk and mathematician, developed an advanced water-powered clock. Later, in the Song Dynasty, Su Song created a monumental mechanical clock tower, complete with an escapement mechanism and an astronomical armillary sphere.

This invention was not just about marking hours; it represented a fusion of science, engineering, and astronomy. Precise timekeeping was vital for governance, ritual, and agriculture. It reflected the Chinese emphasis on harmony between human activities and cosmic cycles.

The mechanical clock spread beyond China, influencing later developments in Islamic and European horology. The tick of a clock, a sound we take for granted today, carries within it the echo of ancient Chinese innovation.

Medicine and Acupuncture: Healing Arts of the East

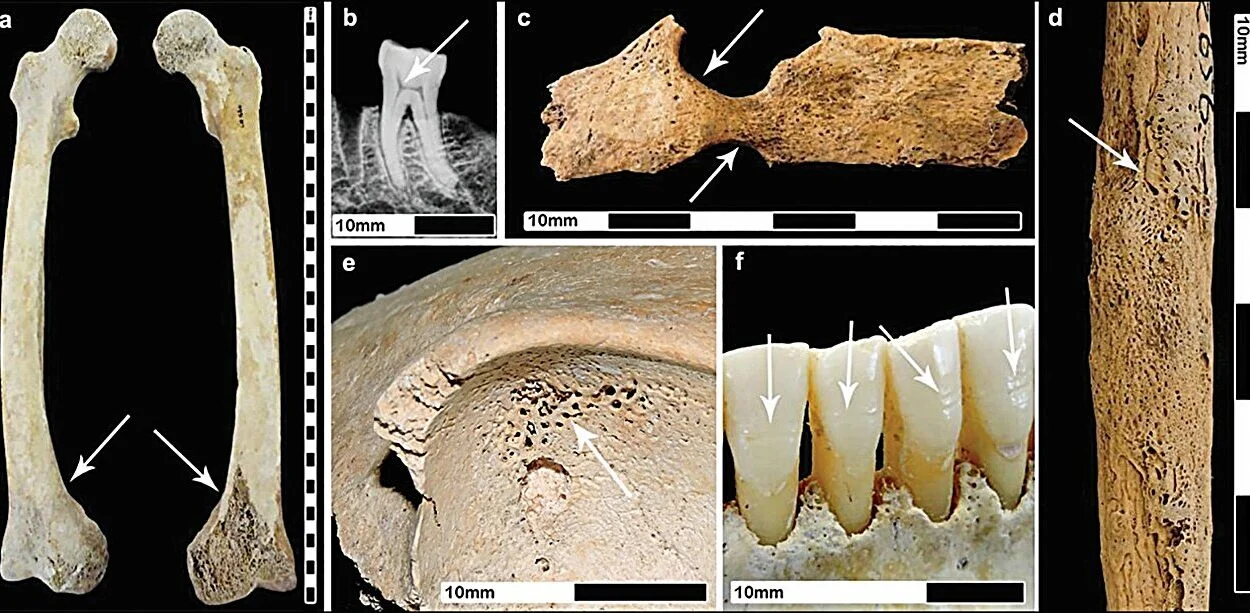

Another field where China made lasting contributions was medicine. Traditional Chinese medicine, rooted in the concepts of balance and energy flow, developed sophisticated practices such as herbal remedies and acupuncture.

Acupuncture, the practice of inserting fine needles into specific points of the body, aimed to restore balance in the flow of qi, or life energy. While debated in modern medicine, acupuncture remains a respected practice worldwide and has gained recognition for its effectiveness in pain management and holistic health.

Chinese herbal medicine cataloged thousands of plants and their uses, influencing both Eastern and Western pharmacopeias. The Huangdi Neijing (Yellow Emperor’s Inner Canon), compiled more than two millennia ago, remains one of the foundational texts of Chinese medical philosophy.

These inventions in healing were not just about curing disease but about understanding the human body, its relationship with nature, and the pursuit of harmony between health and environment.

Porcelain: The Art of Earth and Fire

Porcelain, often called “china” in the West, was another innovation that reshaped global culture. Perfected during the Tang and Song dynasties, porcelain combined strength, lightness, and beauty. Its translucent quality and durability set it apart from ordinary pottery.

Chinese porcelain became one of the most desired commodities in the world. It was traded across Asia, the Middle East, and Europe, influencing local ceramic traditions. Entire industries in Europe later sought to replicate it, but the secret of true porcelain remained in Chinese hands for centuries.

Porcelain was not merely functional—it was an art form, carrying intricate designs, glazes, and cultural motifs. Each piece told a story of craftsmanship, aesthetics, and innovation. It symbolized the refinement of Chinese civilization and its influence on global culture.

Conclusion: The Legacy of Ancient Chinese Inventions

Ancient China was not only a land of dynasties, philosophies, and great walls; it was a land of inventors whose ideas continue to shape the world. From paper to printing, from the compass to gunpowder, from silk to porcelain, Chinese innovations built bridges across continents and centuries. They empowered civilizations, transformed economies, altered warfare, and enriched culture.

These inventions remind us that human progress is not the gift of a single culture but the shared achievement of humanity. Yet, the contributions of ancient China stand out as beacons of creativity and foresight. They reveal a civilization deeply attuned to both practical needs and the mysteries of nature, capable of turning curiosity into world-changing discoveries.

The story of ancient Chinese inventions is not just about the past—it is about how ideas travel, transform, and endure. It is a testament to the human spirit of innovation, a reminder that the tools we use every day—from books and clocks to compasses and fireworks—carry within them the brilliance of those who lived thousands of years before us.

Ancient China’s inventions did more than change history; they continue to shape our present and guide our future.