High in the misty highlands of western Honduras, nestled in the rugged embrace of the El Gigante Rockshelter, scientists are peeling back time itself—layer by layer, seed by seed. And what they’re finding may not only rewrite the early history of farming but offer a lifeline to a fruit—and an industry—facing an uncertain future.

Avocados, the beloved green jewels of toast, guacamole, and billion-dollar agricultural markets, trace their ancestry not to boardrooms or commercial farms, but to humble roots cared for by ancient hands. New research led by Dr. Heather B. Thakar, an anthropological archaeologist at Texas A&M University, reveals that avocados have been cultivated and consciously shaped by humans for over 11,000 years, longer than nearly any other crop in the Americas.

But the story isn’t just about ancient diets or botanical timelines. It’s about survival—of people, of plants, and of a planet. As modern avocado production leans precariously on a single clone—the ubiquitous Hass variety—this archaeological discovery hints at a path toward greater resilience: one that draws wisdom not from laboratories, but from the deep memory of seeds.

A Hidden Archive Beneath Stone and Soil

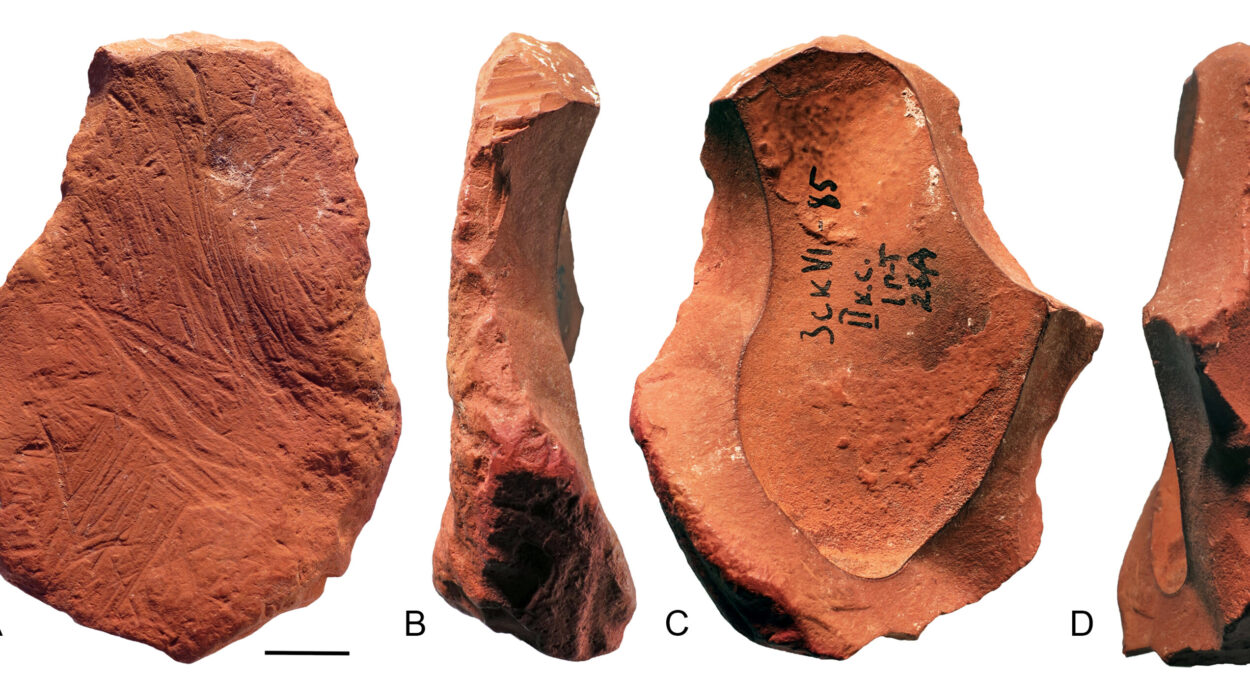

El Gigante, the site of Thakar’s groundbreaking study, is a rare archaeological jewel. In a tropical region where humidity usually destroys organic material, this rock shelter has defied the odds. Protected beneath overhangs and tucked into high elevations, fossilized plant remains have been preserved with astonishing clarity. Among them: thousands of avocado pits, skins, and rinds spanning from the Ice Age to pre-Columbian times.

“It’s truly incredible,” Thakar says. “To find this level of plant preservation in a tropical setting is like finding a well-preserved manuscript in a rainstorm.”

Her team’s work, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, paints a vivid picture of early human interaction with avocado trees. These ancient farmers weren’t merely foraging—they were selecting, pruning, and planting with purpose. Over generations, they cultivated larger fruits with thicker skins—traits that made avocados easier to store, transport, and consume. By 7,500 years ago, early agriculturalists in Honduras had domesticated the avocado, well before the rise of Mesoamerica’s famous trio of maize, beans, and squash.

Giants Gone, Humans Rise

But avocados didn’t evolve for humans. Originally, they were nature’s gift to giants.

Before the rise of humans as agricultural stewards, avocados relied on the continent’s massive Ice Age herbivores—mammoths, gomphotheres, and giant sloths—to spread their seeds. The fruits were large, fatty, and built to survive a journey through a giant’s gut. But when these megafauna went extinct, the tree faced an ecological crisis.

Enter Homo sapiens.

“We filled the void,” says Thakar. “Through forest management and seed selection, people became the avocado’s new ecological partner.”

What followed was a slow, adaptive dance between people and plant—a silent agreement encoded in the shape and size of the seeds they left behind. Using hundreds of radiocarbon dates, Thakar’s team was able to trace this evolutionary story in detail, showing a gradual but deliberate trend toward domestication over thousands of years.

Ancient Lessons for Modern Perils

Why does this matter now? Because today’s avocado industry is a house built on a single genetic foundation: the Hass avocado, a 20th-century cultivar cloned millions of times for its creamy flesh and shipping durability. But monoculture, while economically efficient, is biologically brittle.

“If a major disease or climate shift hits the Hass variety hard, we could face catastrophic losses,” warns Thakar.

The solution may lie not in reinventing the avocado, but in rediscovering it. Thakar emphasizes that wild avocado varieties still exist in Mexico and Central America, many carrying genetic traits lost in commercial strains—traits that could help the fruit withstand pests, drought, or heat. By integrating ancient diversity with modern breeding techniques, scientists could create avocados that are not only tastier or more transportable, but also adapted to a warming world.

“By looking backward, we may find the tools we need to move forward,” she says.

More Than Just Avocados

El Gigante’s bounty doesn’t stop at avocados. The site is a botanical treasure chest, preserving traces of early squash, maize, and other crops that offer similar insights into the domestication of food. Thakar is currently preparing a new publication detailing 4,500 years of maize evolution, illuminating how this staple grain was refined long before the rise of empires or cities.

And the rockshelter itself is drawing global attention. El Gigante has been recognized as one of Central America’s most important archaeological discoveries in decades. Thakar and her colleagues are now working closely with the Honduran government to nominate the site for UNESCO World Heritage status.

“Everything we’re doing—every pit we carbon date, every layer we excavate—is part of a larger effort to protect and understand this irreplaceable site,” Thakar explains.

Seeds of Knowledge, Roots of Survival

Despite its remote location and difficult access—requiring a steep climb to enter—El Gigante has remained remarkably intact. Its deepest layers, undisturbed by looters, preserve a living record of how humans once adapted to a changing world, using ingenuity, patience, and a profound understanding of their environment.

In Thakar’s view, archaeology isn’t just about the past. It’s about preparing for what’s to come.

“When there are no written records, it’s the seeds that tell our story,” she says. “These ancient people faced climate shifts, species extinctions, and ecological uncertainty—just like we do today. Their solutions may not be ours, but their resilience can inspire how we face the challenges ahead.”

As the planet confronts food insecurity, climate instability, and a pressing need for agricultural innovation, the ancient pits of El Gigante may hold more than history. They may hold hope.

The next time you slice open an avocado, consider this: you’re not just eating a fruit. You’re tasting a 11,000-year collaboration between humans and nature—a story still unfolding, and one that might just help us feed the future.

Reference: Amber M. VanDerwarker et al, Early evidence of avocado domestication from El Gigante Rockshelter, Honduras, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (2025). DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2417072122