For the citizens of the ancient Roman Empire, a day at the amphitheater was more than just an outing. It was a spectacle, a shared cultural event that brought entire communities together to marvel at the raw displays of courage, violence, and domination. The roar of the crowd, the clash of steel, the thunder of animals released from cages—all were meant to remind Romans of the Empire’s might and the human ability to subdue nature itself.

Yet beneath the applause lay a much darker reality. For gladiators, the arena was often a death sentence. And for the animals forced into these brutal games—lions, leopards, elephants, and bears—the amphitheater was a stage of suffering, captivity, and eventual death.

A recent study published in Antiquity sheds new light on this grim history, providing the first direct osteological evidence that brown bears were used in Roman spectacles. Until now, the presence of bears in the arena was known mostly through mosaics, texts, and pottery. The discovery of a battered bear skull from Viminacium, an important Roman city in what is now Serbia, transforms speculation into proof. This finding not only confirms the role of brown bears in the games but also reveals the brutal conditions they endured.

A Skull That Tells a Story

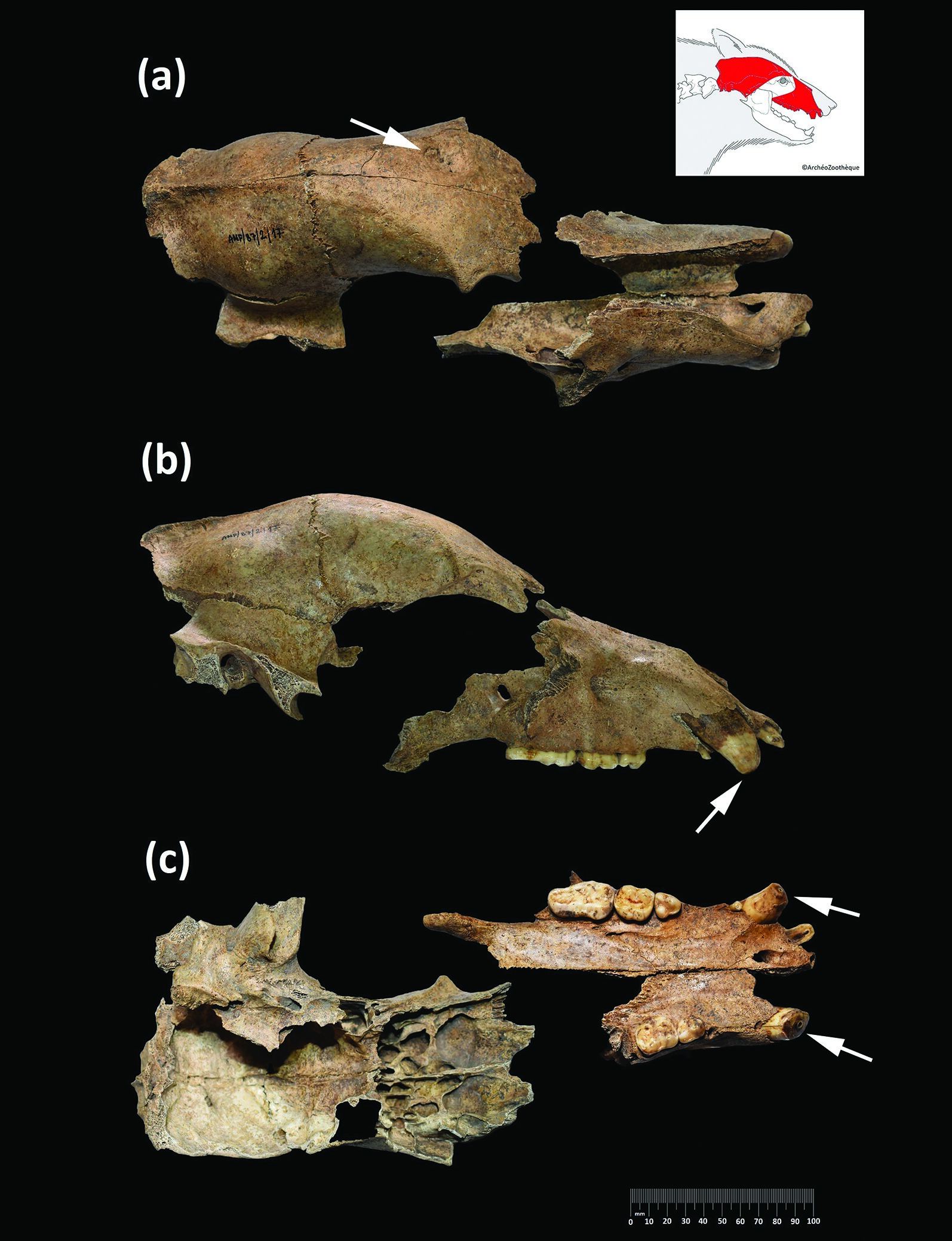

The bear’s remains were uncovered in 2016 near the entrance of a second-century amphitheater in Viminacium. At first glance, it might have seemed like just another fragment from the city’s layered past. But closer inspection revealed a haunting story written into its bones.

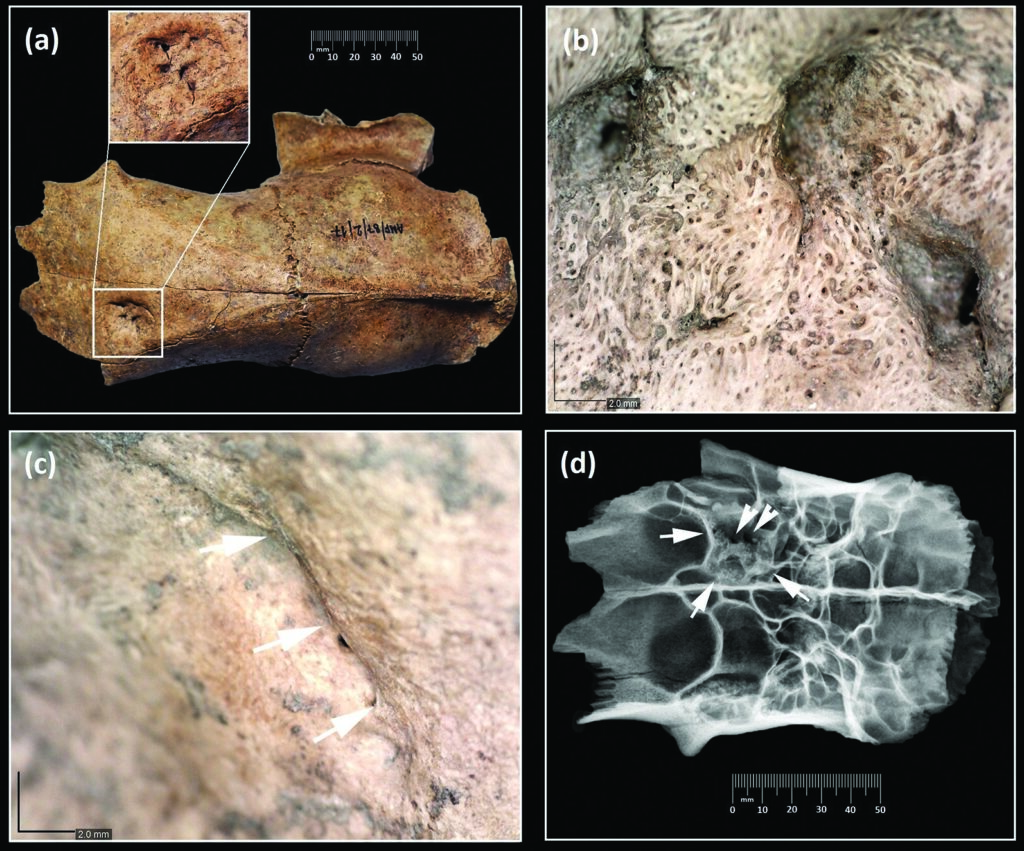

The skull belonged to a male brown bear, roughly six years old at the time of its death about 1,700 years ago. A large fracture ran across its frontal bone, the kind of injury caused by a heavy blow from a weapon such as a spear. What makes the injury especially telling is that it had begun to heal. The bear had survived the blow but suffered greatly afterward.

X-ray images and CT scans revealed signs of infection around the wound, specifically osteomyelitis, an inflammation of the bone triggered by bacteria. The bear’s jaws showed similar damage, suggesting prolonged suffering. It was not a clean, swift death in the arena. Instead, this animal endured a slow decline, its body marked by pain and disease.

Captivity Written in Teeth

One of the most striking pieces of evidence came from the bear’s teeth. Its canines were worn down far beyond what would be expected in a wild animal. In nature, brown bears use their teeth for hunting and eating, but such extreme wear and tear is unusual.

In captivity, however, it is common. Animals confined in cages often gnaw at the bars in frustration, anxiety, or desperation. This repeated behavior wears down the teeth over time, leaving behind clear evidence of psychological distress. The damage in this bear’s mouth tells us that it was not captured and killed quickly for a single show. Instead, it was likely held in captivity for years, dragged out repeatedly for spectacle after spectacle.

The amphitheater at Viminacium may have seen this bear face hunters, other animals, or even trained gladiators. Each fight would have been another round of torment, cheered on by crowds who viewed the animal’s suffering as entertainment.

Between Life and Death

The researchers who studied the skull cannot say with certainty how the bear died. The evidence suggests that the fracture to its skull was not instantly fatal but instead led to a long, painful infection. Perhaps the injury occurred during a spectacle, a blow struck by a hunter in front of a roaring audience. Perhaps the bear was kept alive afterward, weakened and suffering, until infection finally ended its life.

What is clear is that its story does not end in the moment of combat but stretches across years of captivity, stress, and neglect. Its bones carry the weight of both physical violence and emotional suffering, offering a rare, sobering glimpse into the hidden victims of Rome’s famous games.

The Role of Animals in Roman Entertainment

Romans prided themselves on their ability to dominate nature, and the amphitheater was one of the clearest symbols of that domination. Exotic animals were captured across the empire and transported to Rome and its provinces, where they became living displays of imperial power. To present lions from Africa, elephants from India, or bears from the forests of Europe was to demonstrate the empire’s reach and mastery over the natural world.

But these spectacles came at a tremendous cost. Thousands of animals were slaughtered in games that might last for days. Ancient sources describe events where entire species were nearly wiped out in certain regions due to overhunting for entertainment. For the Romans in the stands, this was thrilling theater. For the animals in the cages, it was a nightmare of confinement and fear.

The brown bear from Viminacium is not just a singular case—it represents countless other animals whose remains have not survived but whose lives were consumed by the Roman appetite for spectacle.

Science Meets History

What makes this discovery so powerful is the way science allows us to connect with the past. Ancient texts and art had long hinted that bears were used in amphitheaters, but the direct evidence was missing. This skull bridges that gap. Through osteology, radiology, and careful analysis, researchers have uncovered not only confirmation but also the lived experience of one individual animal.

By piecing together the fracture, the infections, and the dental wear, scientists reconstruct a biography of suffering. The bear is no longer just a symbol in a mosaic or a nameless figure in a text—it is a once-living creature whose story is written in bone.

A Glimpse of the Brutal Past

The Roman amphitheater is often romanticized as a place of courage, glory, and the thrill of battle. But discoveries like the Viminacium bear remind us of the cost behind the applause. For the humans who fought, it was often slavery and death. For the animals, it was capture, confinement, and cruelty.

This skull forces us to see the games not just from the perspective of the audience but from those who suffered for entertainment. It transforms the amphitheater from a monument of Roman grandeur into a reminder of the darker side of human history—the ability to turn violence into spectacle, to reduce living beings into instruments of amusement.

The Legacy of the Viminacium Bear

Seventeen centuries after its death, the Viminacium bear continues to speak. Its fractured skull, its worn teeth, its infected bones—all testify to a world where entertainment came at the expense of suffering. Thanks to this discovery, the bear is no longer forgotten. Its story adds depth to our understanding of Roman society, reminding us that the past was not only about emperors and victories but also about the voiceless lives caught in the machinery of empire.

The amphitheater may have fallen silent, its stones weathered by time, but the echoes of those spectacles remain. In the bones of one bear, we find a mirror of humanity’s capacity for both cruelty and curiosity. The same civilization that built aqueducts and advanced law also filled its arenas with blood. The story of the Viminacium bear is not just about Rome—it is about us, and the choices we make about how we treat the natural world.

More information: Nemanja Marković et al, A spectacle of the Roman amphitheatre at Viminacium: multiproxy analysis of a brown bear skull, Antiquity (2025). DOI: 10.15184/aqy.2025.10173