Buried in the soil of Northern Kyushu, Japan, are the quiet remains of ancient pots—fractured vessels that once simmered with wild fish and fragrant broths. They do not shout, but they whisper. And if you listen closely, they speak of a mystery: the moment Japan met rice farming—and shrugged.

It’s a story that defies the textbook arc of human history. One in which agriculture marches in like a hero, sweeping away primitive ways, ushering in civilization. But the past is never quite that simple.

New research has unearthed evidence that Japan’s embrace of agriculture—specifically the arrival of rice and millet around 3,000 years ago—didn’t come with the cultural upheaval that scholars have come to expect. In fact, in kitchens and clay pots across the Japanese archipelago, much remained the same. The fish still sizzled. The broth still steamed. And millet, despite traveling thousands of miles across the sea, was all but ignored.

Seeds Across the Sea

The story begins with migration. Long before maps or borders, people from the Korean Peninsula crossed the waters to southern Japan. With them came new ideas, new tools—and two crops that would change the world: rice and millet.

Rice, now synonymous with Japan’s identity, was a foreigner once. So was millet, a grain rich in history and vital to ancient Korean diets. These crops represented something revolutionary. Not just food, but farming. Not just sustenance, but civilization. Historians long assumed their arrival reshaped Japan overnight.

But science has a way of uncovering truths buried beneath assumptions. And according to new findings published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, led by researchers from the University of York, the University of Cambridge, and Japan’s own Nara National Research Institute for Cultural Properties, the reality was far more complex—and deeply human.

Cracking the Code of Cuisine

The breakthrough came not from ancient texts or grand monuments, but from charred residues in pottery. Fragments of meals long gone, preserved like fingerprints in clay. Using cutting-edge organic residue analysis, the team studied the molecular ghosts of food—traces of fats, oils, and plant material absorbed into the ceramic walls of cooking vessels.

What they found was astonishing.

Both rice and millet had indeed arrived in prehistoric Japan. Seed impressions in pottery confirmed their presence. But millet—beloved and essential in Korean cuisine—left almost no trace in the Japanese pots. Nor did it appear in the chemical signatures of human bones from the period. It was as if the grain had arrived… and been politely declined.

Dr. Jasmine Lundy of the University of York explained the significance: “Organic residue analysis gives us a direct window into the everyday choices people made about food. And what we saw is that, despite having access to new grains, people stuck with what they knew—wild plants, fish, and traditional cooking styles.”

The cooking pots didn’t lie. They still bore the markers of marine oils and terrestrial animal fats. They hadn’t been repurposed for boiling grains or crafting new dishes. Instead, they echoed the rhythms of an older world, one still rooted in the bounty of rivers, forests, and the sea.

The Millet That Missed Its Moment

The research raised a haunting question: Why was millet rejected when rice was slowly, though eventually, embraced?

Millet, after all, wasn’t a difficult crop. It grew easily in Japanese soil. Climatic conditions weren’t to blame. It was, in many ways, the perfect food—resilient, nutritious, fast-growing. Yet it made little dent in Japanese culinary life.

Professor Oliver Craig, also from York, expressed the team’s surprise: “We expected millet to show up in the residues, especially given its dominance in Korean Bronze Age diets. But it was absent—almost entirely. That told us something cultural was at play, not environmental.”

In other words, millet didn’t fail because it couldn’t grow. It failed because it didn’t belong.

The Pot That Didn’t Change

The tale becomes even more compelling when one considers the evidence of material culture. Korean-style pottery appeared in Japan during this period. So did farming tools. People were clearly exchanging more than just food—they were trading ideas, intermarrying, blending worlds.

And yet, in kitchens, change came slow.

Dr. Shinya Shoda of the Nara National Research Institute noted, “Even with new farming implements and Korean-inspired ceramics, the fundamental way people cooked stayed the same. The Yayoi pots we examined weren’t designed for rice or millet. They were still being used to cook wild fish and other native foods.”

This resistance wasn’t stubbornness. It was something deeper—a testament to the strength of culinary identity.

Japan’s prehistoric people, inheritors of the Jomon cultural tradition, had long lived as fishers, hunters, and foragers. Their meals were complex and sophisticated, rooted in deep knowledge of seasonal abundance. To ask them to abandon that for grains—even promising ones—may have simply been asking too much, too fast.

When Technology Isn’t Destiny

The findings challenge a central assumption in the story of civilization: that new technology automatically transforms societies. It’s a seductive idea—that invention brings progress, and progress means change.

But Japan’s ancient pots tell a different story.

They remind us that technology is only part of the equation. People, not tools, decide how societies evolve. And sometimes, culture is the force that slows the wheel of progress—not out of ignorance, but out of loyalty to a way of life that works.

The study’s lead investigator, Dr. Enrico Crema from the University of Cambridge, puts it this way: “This isn’t just a story about food. It’s a story about choice. About how cultural practices can persist even in the face of enormous change.”

Lessons from a Steady Flame

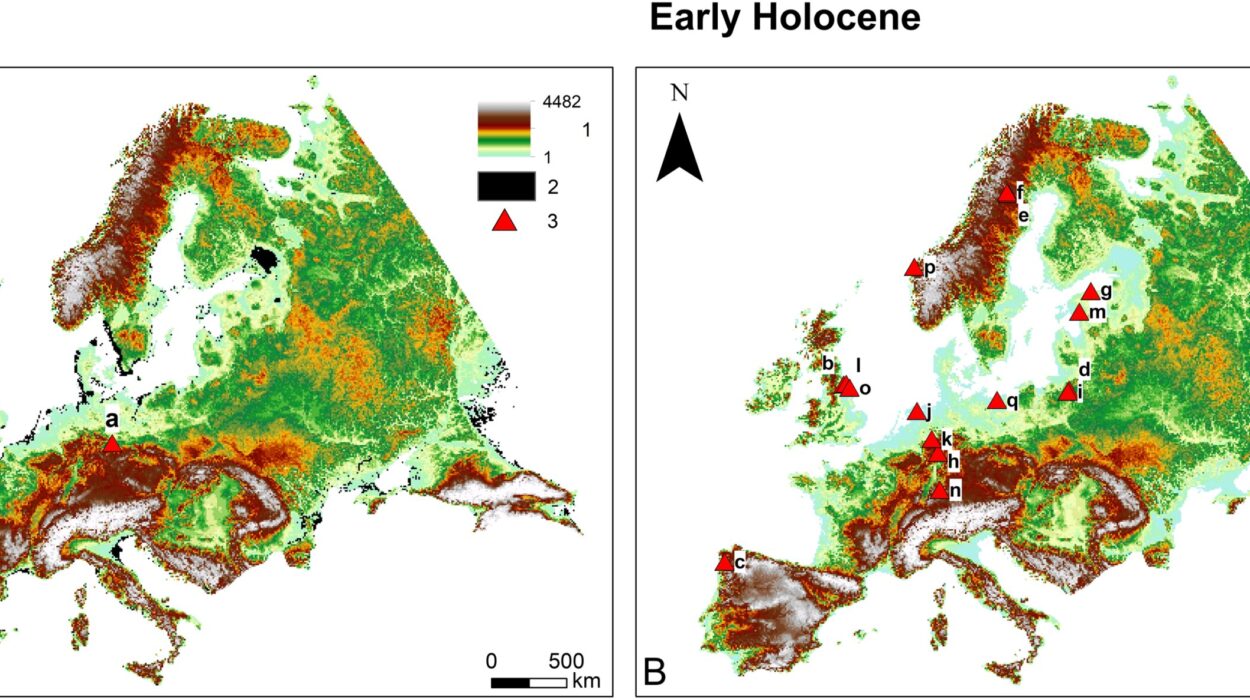

History offers many parallels. In southern Scandinavia, for example, people continued to hunt and fish for generations after farming reached their shores. In Britain, the opposite occurred—wild foods vanished quickly from the menu, replaced by wheat and barley. Across the globe, societies reacted to farming not with uniformity, but with nuance.

Japan’s story belongs to this richer, more complex tapestry of human history.

Eventually, of course, rice did become central to Japanese life. It shaped villages, rituals, and economies. It carved terraces into hillsides and filled poems with longing. But it didn’t conquer the culinary heart of Japan overnight.

And millet? Though largely forgotten in ancient Japan, it still thrives in Korean kitchens—fermented, steamed, ground into flour. A legacy not lost, just planted elsewhere.

The Ghosts in the Pot

There’s something beautiful about this discovery. In the thin black film inside a 3,000-year-old pot, we find not just molecules, but memory. The memory of a mother simmering fish for her children. The memory of a hunter returning with his catch. The memory of a people who met change—and chose to honor their past even as the future beckoned.

It reminds us that culture is more than survival. It’s the flavor of belonging. The rhythm of the familiar. The way a pot is stirred, not because it’s efficient, but because it feels right.

The ancient Japanese didn’t reject millet because they couldn’t grow it. They did so, perhaps, because it didn’t taste like home.

Reference: Oliver E Craig et al, Lipid residue analysis reveals divergent culinary practices in Japan and Korea at the dawn of intensive agriculture, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (2025). DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2504414122. doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2504414122