Around 5,500–6,000 years ago, the land that would one day be called Finland was alive with quiet movement along water routes. Small communities of hunter-fisher-gatherers clustered near rivers and shores, traveling by boat, returning season after season to familiar places. They built lasting fishing systems, and at times even cleared forests to make room for small-scale farming. These were not wandering bands passing through. They were people rooted in place, tied to water, land, and memory.

Yet one of the most enduring traces they left behind was not a structure, a tool, or a settlement. It was a color.

Across cliffs overlooking waterways, they painted elk and boats in a blazing red made from ochre, an iron-rich earth pigment. They brushed the same red onto their dead and onto objects placed in graves. To modern eyes, the color alone is striking. But new research suggests that for these Stone Age communities, ochre carried layers of meaning far deeper than its fiery hue.

The Cliffs That Spoke Without Words

The prominent cliffs chosen for these paintings were not random. Rising above the waterways that connected villages, they marked central points in a world navigated by canoe and current. There was no modern concept of land ownership, but these red images of animals and boats acted as quiet declarations. Someone had been here. Someone mattered here.

Ochre stained more than stone. It marked bodies and belongings laid carefully into graves. In death, as in life, red followed them. Archaeologists have long known that ochre played a role in Stone Age ritual, but until now, its deeper story in Finland remained largely untold.

That began to change when a research group from the University of Helsinki decided to look past the color itself and into the material hidden within it.

A Question Hidden in the Red Earth

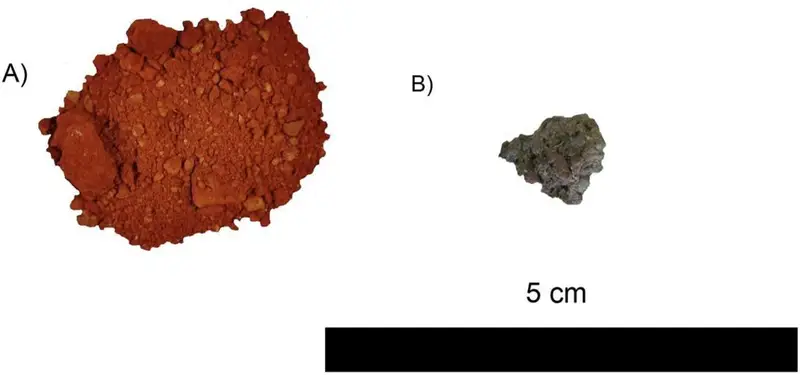

At first glance, ochre seems simple. It is red earth, ground and mixed, applied by hand. But what if not all ochre was the same? What if the pigment placed on one person differed subtly from that placed on another, even within the same grave?

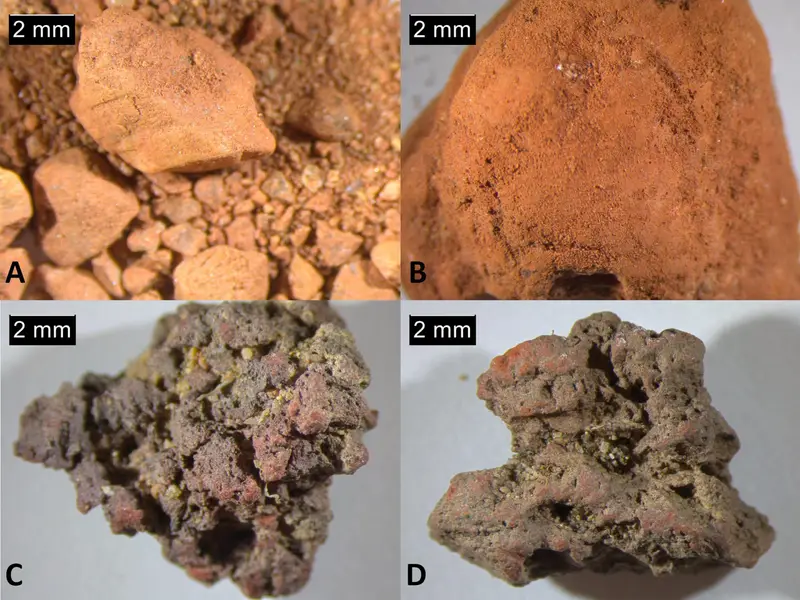

To answer that question, researchers turned to the Typical Comb Ware culture, a Stone Age culture associated with the graves and settlements under study. They collected ochre samples from burial sites and living areas and examined their chemical composition using X-ray fluorescence (XRF) and scanning electron microscopy with energy-dispersive spectroscopy (SEM-EDS). These techniques allowed them to read the elemental fingerprints of each sample.

What emerged from the data was unexpected.

Different Reds for Different People

The researchers found clear variation in chemical composition among ochre samples, even those taken from the same grave. In some cases, the pigment used on one individual or object differed chemically from the pigment used on another, though both were buried side by side.

This meant that the ochre had not come from a single source. Multiple origins were represented in a single ritual space.

As one researcher explained, color alone was not the deciding factor. The people who buried their dead seemed to care about where the ochre came from, not just how it looked. Perhaps the source of the pigment marked individual identity. Perhaps the journey the ochre took carried symbolic weight. The research does not assign a single explanation, but it makes one thing clear. For these communities, meaning was layered into materials themselves.

The First Time Finland’s Ochre Was Truly Studied

This study, published in the Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, represents the first geochemical analysis of archaeological ochre in Finland. According to researcher Marja Ahola, although the ritual use of ochre has long been recognized, its chemical diversity had never been examined in this region before.

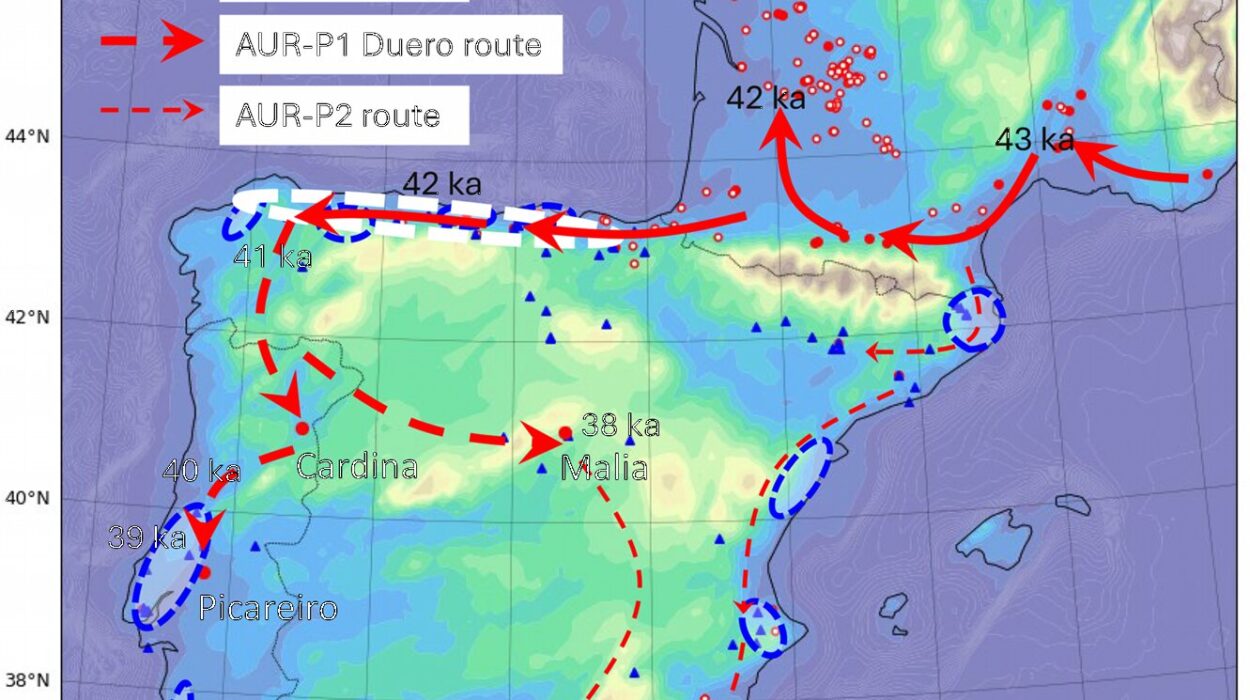

By identifying distinct chemical signatures, the researchers were able to link certain ochre types to specific geographical areas. Some varieties clustered tightly in particular regions, suggesting local sources. Others appeared far from where they naturally occurred.

That distance mattered.

Following the Pigment’s Long Road

When chemically similar ochre appeared hundreds of kilometers apart, it told a story of movement. These pigments were not simply dug up nearby and used on the spot. They traveled.

The researchers suggest that ochre moved through the same exchange networks that carried other valued materials of the era. Amber from the Baltic region and ring-shaped slate ornaments from the Lake Onega region are known to have circulated widely, passing from group to group across vast distances. Ochre, it seems, joined this flow.

From this perspective, long-distance movement was not exceptional. It was typical. Objects, raw materials, and the meanings attached to them crossed forests, lakes, and rivers, binding distant communities together in shared systems of exchange.

Rituals Built from Many Sources

One of the most intriguing findings was not just that ochre came from far away, but that multiple types of ochre were deliberately used together in the same ritual contexts. This was not accidental mixing or careless reuse. It was choice.

Different pigments, each with its own origin and journey, converged in a single grave or ceremonial act. The red earth became a meeting point of places, paths, and people.

This suggests that rituals were not only about honoring the dead, but also about acknowledging connections beyond the local landscape. Each application of ochre may have carried with it stories of travel, exchange, and relationships reaching far beyond the burial site itself.

A World Painted with Meaning

Taken together, the findings reshape how we understand these early Finnish communities. They were not isolated groups using whatever materials lay closest at hand. They lived in a world threaded together by waterways and exchange routes, where materials carried biographies as rich as those of the people who used them.

Ochre was not just decoration. It was not just symbolism in a general sense. It was a material chosen with care, sometimes transported across great distances, sometimes combined deliberately with other pigments, and applied in moments of deep ritual importance.

The red painted on cliffs and graves was part of a broader language, one spoken without words but rich in intent.

Why This Research Matters

This study matters because it shows how much human intention can be hidden in seemingly simple materials. By looking closely at the chemistry of ochre, researchers uncovered social networks, ritual choices, and expressions of identity that would otherwise remain invisible.

It reminds us that even thousands of years ago, people made deliberate decisions about what they used, where it came from, and what it meant. Color was only the surface. Beneath it lay journeys, connections, and values carried across landscapes and generations.

In the end, the red earth of Stone Age Finland tells a quiet but powerful story. It speaks of people who understood that materials could hold memory, that distance could add meaning, and that even in death, the choices made by the living mattered deeply.

Study Details

Elisabeth Holmqvist et al, Non-invasive chemical characterisation of archaeological ochres from the early 4th millennium BCE forager graves and settlements in Finland, Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports (2026). DOI: 10.1016/j.jasrep.2026.105584