Anyone who has watched a scraped knee linger or a pulled muscle take its time to mend later in life knows the quiet frustration of aging bodies. The skin closes more slowly. Strength returns in hesitant steps. For years, this slowdown has been treated as a simple failure of aging tissues to do what they once did with ease. But a new study from UCLA invites us to look closer, and to see something far more complicated unfolding beneath the surface.

In research published in Science, scientists studying mice discovered that aging muscles do not heal slowly just because they are worn out. Instead, the very cells responsible for repair appear to have made a difficult choice. They trade speed for survival. They become less effective healers, not because they are broken, but because they are trying to stay alive.

This shift reframes aging not as a story of pure decline, but as one of compromise. And it begins with a single protein quietly accumulating inside aging muscle stem cells.

Inside the Cells That Mend Muscle

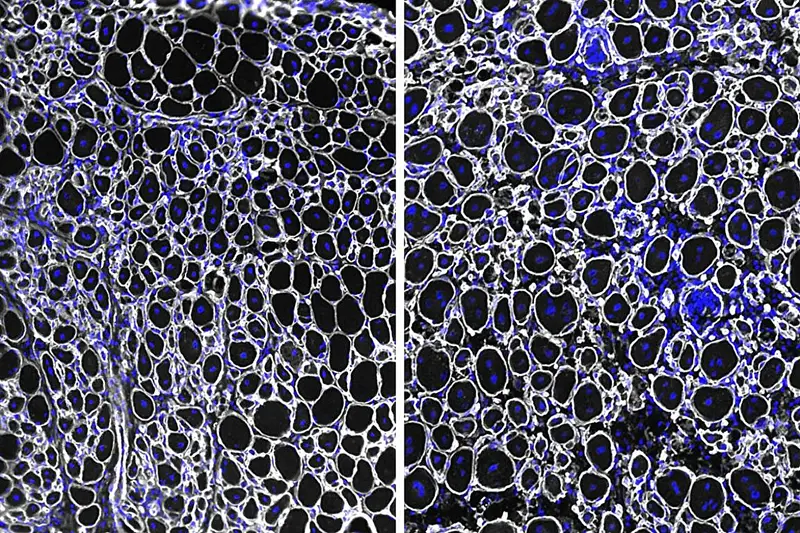

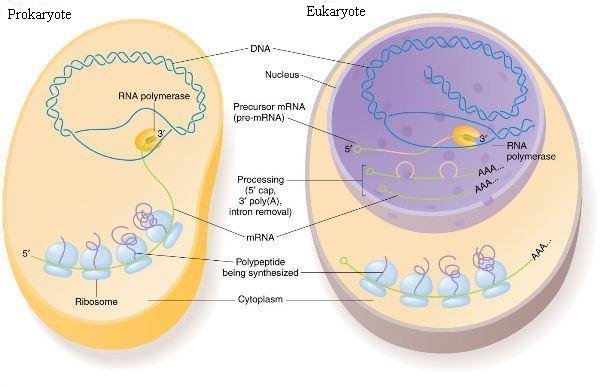

Muscle repair depends on a small population of muscle stem cells, sometimes called satellite cells. When injury strikes, these cells awaken from dormancy, multiply, and rebuild damaged tissue. In young muscle, this process is swift and efficient. In older muscle, it slows dramatically.

To understand why, the UCLA team, led by postdoctoral scholars Jengmin Kang and Daniel Benjamin, compared muscle stem cells taken from young mice and from aged mice. What they found was striking. A protein called NDRG1 was present at far higher levels in the old cells, reaching 3.5 times higher than in young ones.

This was not a minor fluctuation. It was a dramatic accumulation, and it seemed to change everything about how these cells behaved.

The Brake Pedal No One Expected

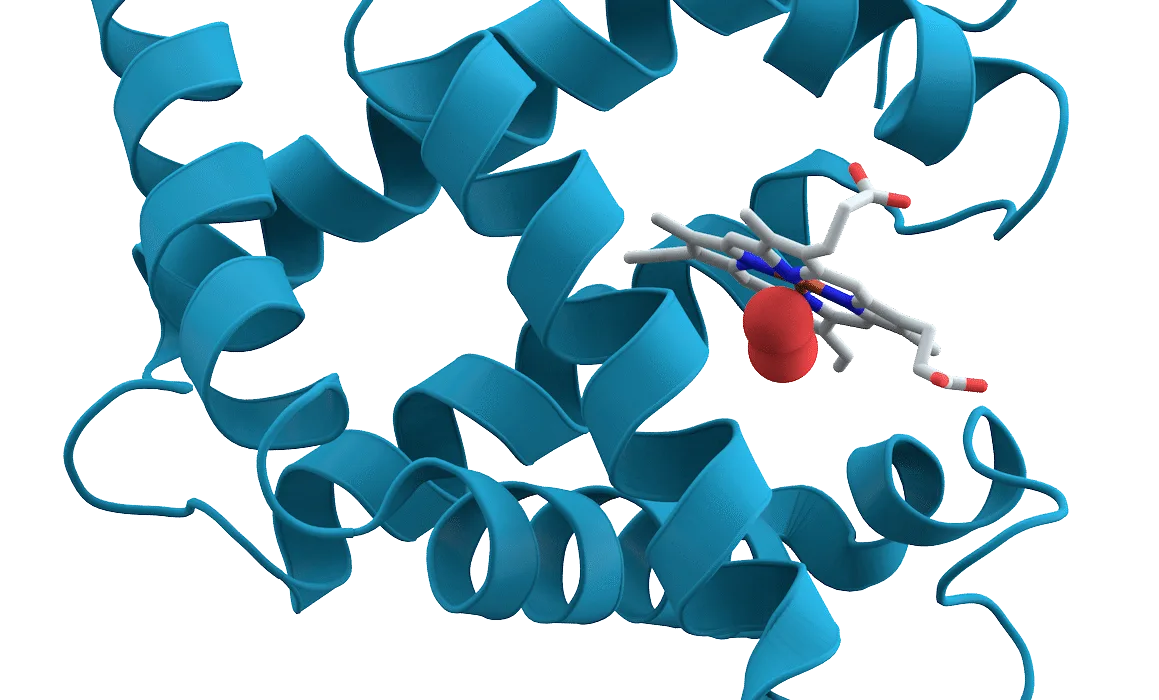

The protein NDRG1 acts like a cellular brake. It suppresses a major signaling pathway known as mTOR, which normally encourages cells to activate, grow, and divide. In young muscle stem cells, mTOR helps trigger rapid repair after injury. In older cells, rising NDRG1 levels press down on that accelerator.

The result is a stem cell that hesitates. It activates more slowly. It repairs tissue less efficiently. From the outside, this looks like failure.

But when the researchers looked deeper, they saw another side of the story. While these older stem cells were slower to respond, they were far more likely to survive in the harsh environment of aging tissue. The very mechanism that dulled their healing power appeared to protect them from dying.

This realization forced a rethink of what aging really means at the cellular level.

Rewinding the Clock, With a Catch

To test whether NDRG1 was truly responsible for the sluggish repair seen in older muscles, the team designed a bold experiment. They allowed mice to age naturally to what the researchers described as the equivalent of about 75 human years. Then, they blocked the activity of NDRG1 in the aged muscle stem cells.

The response was immediate and dramatic. Cells that had been slow and cautious suddenly behaved like young ones again. They activated quickly. They accelerated muscle repair after injury. For a moment, aging seemed reversible.

But the victory was short-lived.

Without NDRG1’s protective influence, fewer muscle stem cells survived over time. The very intervention that restored youthful function also made the cells vulnerable. After repeated injuries, the muscle’s ability to regenerate declined, not because the cells were inactive, but because there were fewer of them left.

It was a powerful reminder that biology rarely gives gifts without consequences.

Sprinters, Marathon Runners, and Aging Cells

To explain this paradox, senior author Dr. Thomas Rando, director of the Eli and Edythe Broad Center of Regenerative Medicine and Stem Cell Research at UCLA, offered an image that makes the science feel human.

Young muscle stem cells, he said, are like sprinters. They are fast, explosive, and exceptionally good at their job. But they burn through their energy quickly. They excel in short bursts, not long races.

Aged stem cells, by contrast, resemble marathon runners. They are slower off the starting line, but they endure. They survive the long haul of aging tissue, where resources are limited and stress is constant.

What makes them resilient over time is precisely what makes them poor at rapid repair. The traits that help them live longer hold them back when speed is required.

This analogy captures the heart of the study. Aging does not simply weed out weak cells and leave strong ones behind. It selects for cells that can endure, even if endurance comes at the cost of performance.

Survival of the Slowest

As the team validated their findings through multiple approaches, studying muscle stem cells both in laboratory dishes and within living tissue, the pattern held. NDRG1 accumulation consistently slowed activation and repair while enhancing survival and resilience.

From this, the researchers proposed a concept they call cellular survivorship bias. Over time, stem cells that fail to accumulate enough NDRG1 are more likely to die. What remains is a population of cells that are slower, tougher, and better adapted to survive the stresses of aging.

In this light, age-related decline begins to look less like a flaw and more like a filter. The body preserves what can last, even if what lasts cannot perform as brilliantly as before.

“Some age-related changes that look detrimental,” Rando explained, “may actually be necessary compromises that prevent something worse: the complete depletion of the stem cell pool.”

Echoes of Evolution in Aging Tissue

Rando sees this cellular behavior as part of a much larger story, one that echoes patterns found throughout nature. In harsh environments, animals often activate resilience programs that prioritize survival over reproduction. During droughts, famines, or freezing temperatures, life slows down to endure.

Stem cells, it appears, do something similar as tissues age. They shift resources away from their reproductive role of making new cells and toward survival programs that help them persist.

At the species level, survival depends on reproduction. At the cellular level, survival sometimes requires stepping back from it. The same trade-offs that shape evolution across generations seem to play out inside individual tissues over time.

“It’s exactly aligned with what we’re seeing at the cellular level,” Rando said. Aging, in this view, is not a breakdown of strategy, but a change in priorities.

The Temptation to Fix What Isn’t Broken

The findings inevitably raise questions about future therapies. If blocking NDRG1 can restore youthful function, could similar approaches help aging muscles heal faster in humans?

Rando urges caution. “There’s no free lunch,” he warned. Improving function, even temporarily, may come with hidden costs. Enhancing activation without protecting survival could drain the very stem cell pool tissues depend on.

The challenge ahead is not simply to make aged cells act young again, but to understand how to balance activation and survival. The team plans to continue investigating what controls this delicate equilibrium at the molecular level.

In this sense, NDRG1 becomes more than a protein. It becomes a doorway into understanding the trade-offs that govern aging itself.

Why This Research Matters

This study matters because it changes the story we tell about aging. Instead of viewing slower healing as a straightforward failure, it reveals a deeper logic at work. Aging tissues are not merely losing function. They are adapting to survive.

By showing that molecular changes like increased NDRG1 can be both protective and limiting, the research highlights the complexity of biological aging. It suggests that any attempt to intervene must respect the balance cells have struck over time.

Understanding these trade-offs does more than inform potential therapies. It reshapes how we think about growing older. Aging is not just about what is lost, but about what is preserved, often quietly and at great cost.

In the slow healing of aging muscle lies a story of resilience. Not perfect, not efficient, but enduring. And sometimes, endurance is the most remarkable adaptation of all.

Study Details

Jengmin Kang et al, Cellular survivorship bias as a mechanistic driver of muscle stem cell aging, Science (2026). DOI: 10.1126/science.ads9175