Near the northern Syrian city of Afrin, beneath layers of stone that once lay at the bottom of a warm Eocene sea, an extraordinary discovery has brought the ancient world back to life. An international team of researchers has identified a new fossil sea turtle, now named Syriemys lelunensis.

This remarkable find, published in Papers in Palaeontology, represents not only the first newly described fossil vertebrate species from Syria, but also a critical piece in the story of how ancient marine reptiles spread across our planet. The turtle lived approximately 50 million years ago, during the early Eocene epoch—a time when Earth was warmer, seas were higher, and life flourished in newly evolving ecosystems after the extinction of the dinosaurs.

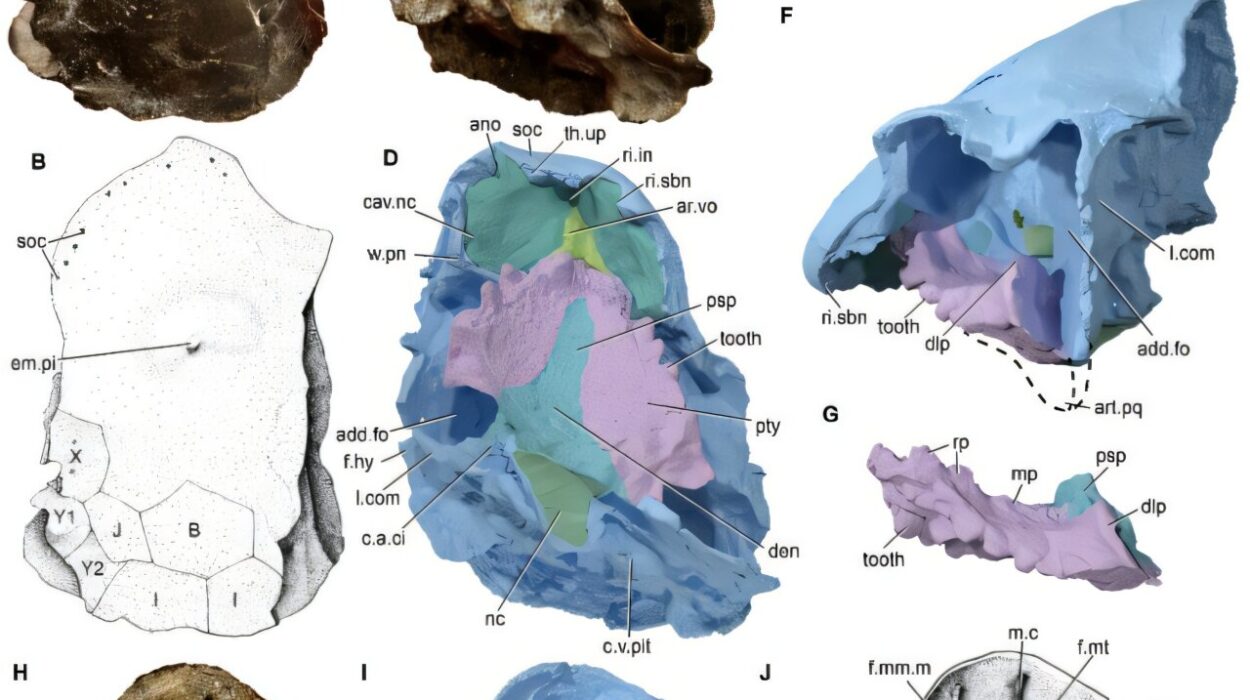

The fossil itself includes a beautifully preserved internal cast of the shell, several bones of the underside of the carapace, pelvic bones, and hind limbs. With a carapace measuring 53 centimeters long and 44 centimeters wide, this turtle would have been a graceful inhabitant of the ancient seas that covered what is today the Middle East.

A Fossil’s Long Journey

The discovery of Syriemys lelunensis is a story not only of science but of resilience. The fossil fragments were first uncovered in 2010 during a blast at the Al-Zarefeh quarry near Afrin. For more than a decade, they rested quietly in the offices of the General Directorate of Geology and Mineral Resources in Aleppo, largely unstudied as conflict swept across Syria.

It was not until Wafa Adel Alhalabi, a Syrian-Brazilian paleontologist at the University of São Paulo, revisited these specimens with an international team of scientists from Brazil, Syria, Germany, Lebanon, and Canada that the true significance of the fossil emerged. “For 13 years, these bones waited,” Alhalabi explained. “And now, we have finally given them a voice.”

Naming a Turtle from the Past

The name Syriemys lelunensis carries both scientific and symbolic meaning. “Syriemys” links the fossil to its country of discovery, honoring Syria’s deep geological and cultural history. The second part of the name, lelunensis, reflects the specific locality where the fossil was found. By naming the species in this way, the researchers ensured that Syria itself will forever be tied to the global story of paleontology.

The fossil is especially significant because it extends the known history of an extinct group of side-necked turtles called the Stereogenyini. Until now, fossils of this group had been found across South America, North America, the Caribbean, Africa, and Asia. The discovery in Syria suggests that these turtles may have had Mediterranean origins, pushing their lineage back more than 10 million years earlier than previously thought.

Reading the Rock for Clues

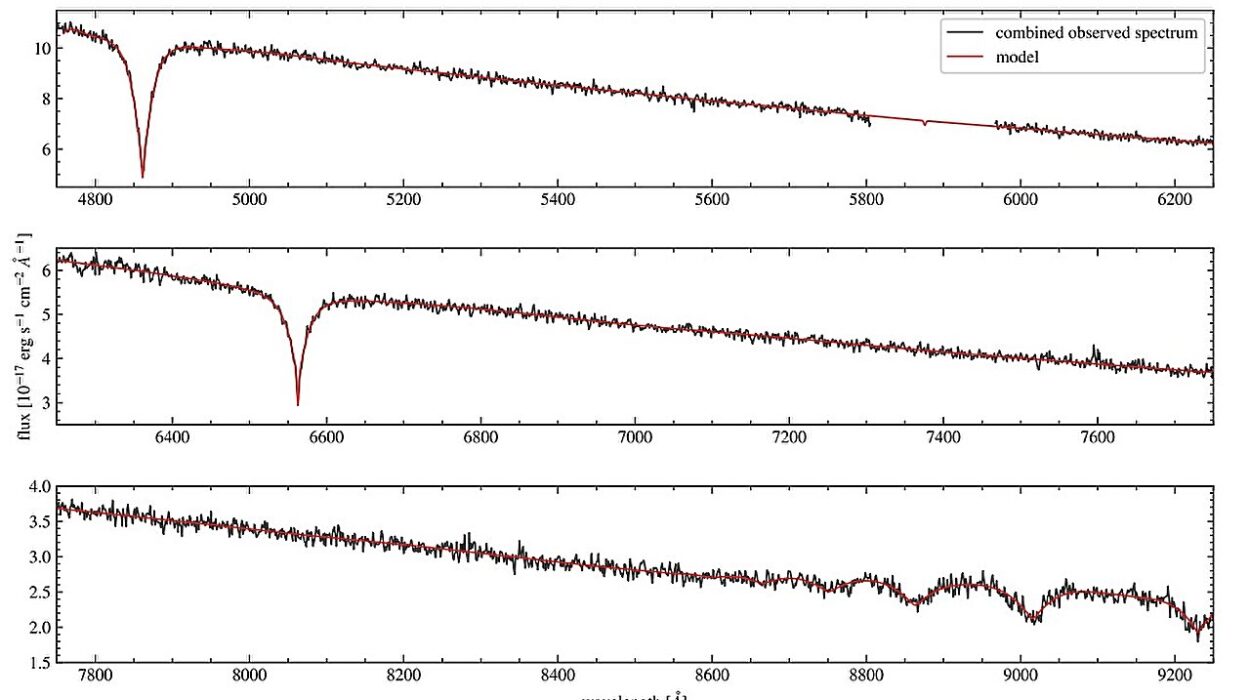

To determine the age of the fossil, scientists turned not only to the bones themselves but also to the tiny organisms fossilized alongside them. In the surrounding rock, the team identified foraminifera—microscopic shell-bearing protozoa that serve as timekeepers of Earth’s history. By analyzing these fossils, researchers were able to confidently date Syriemys lelunensis to the early Eocene, around 50 million years ago.

This method reflects the beauty of paleontology: every fossil is not only the record of an animal but also a snapshot of an entire ecosystem. The shells of ancient microorganisms, preserved alongside the turtle, provide a precise context, anchoring this discovery in deep time.

A Sea Where Syria Stands

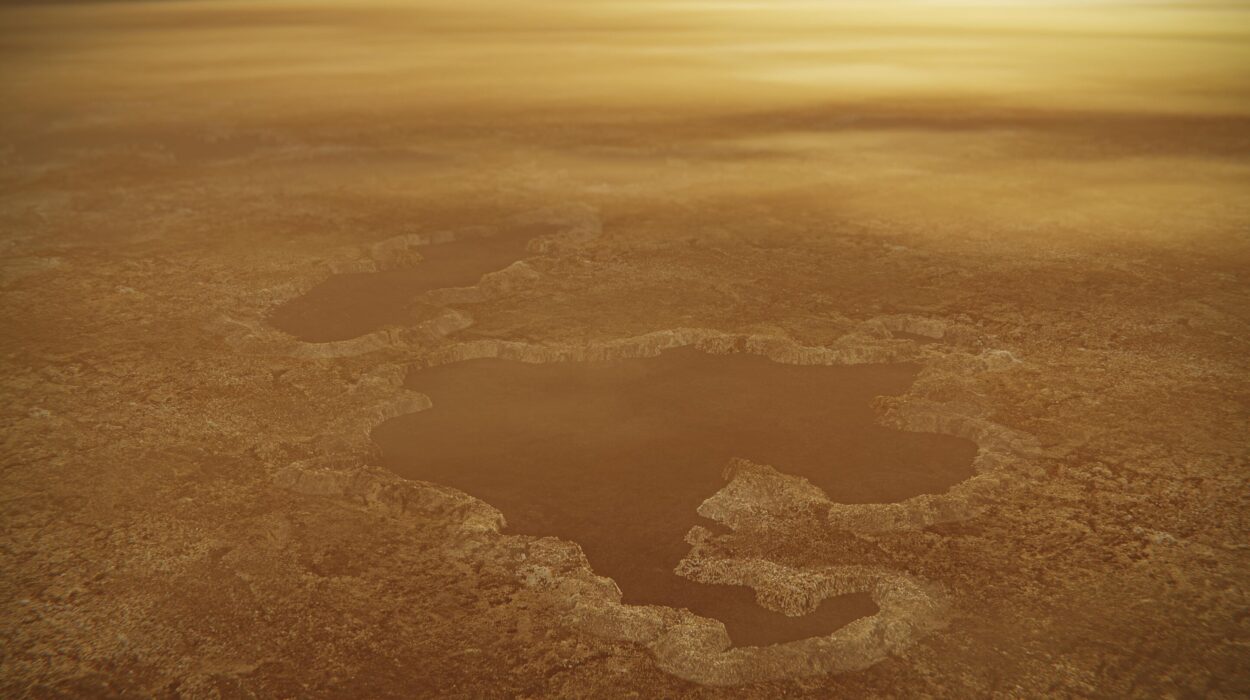

To modern eyes, it may seem strange to find a sea turtle fossil in the arid landscapes of Syria. Yet, during much of Earth’s history, the Middle East was underwater. From the Cretaceous period some 145 million years ago until the late Miocene about 5 million years ago, present-day Syria lay beneath vast shallow seas.

These ancient waters nurtured a rich variety of marine life, from corals and mollusks to reptiles like turtles. “Given this extensive marine past, it is not surprising to find a sea turtle here,” explained Dr. Gabriel Ferreira of the Senckenberg Center for Human Evolution and Paleoenvironment at the University of Tübingen. “But what is exciting is that this discovery adds Syria to the global distribution of the Stereogenyini—and perhaps even suggests the group’s birthplace.”

Science Amidst Struggle

What makes this discovery particularly poignant is the context in which it was made. Syria has endured years of conflict, and for much of that time scientific research was disrupted, collections neglected, and international collaborations halted. Against this backdrop, the discovery of Syriemys lelunensis is a reminder that science persists even in the face of tragedy.

“The current situation in Syria is extremely complex, and in view of the tragedies unfolding there, it seems almost surreal to talk about fossils,” said Professor Max Langer of the University of São Paulo, senior author of the study. “But at the same time, this publication illustrates the country’s scientific potential and the fact that science is still alive there.”

The research team has even launched a new initiative titled Recovering Lost Time in Syria, a series of studies based on fossils that were observed and documented before or during the war. The project’s name reflects both geological time and the lost years of Syrian science, offering a hopeful path forward.

An Ancient Life Remembered

The fossil of Syriemys lelunensis is more than just stone—it is a window into a vanished world. This turtle swam in warm, shallow seas, gliding gracefully through waters that teemed with life. Its bones, preserved for 50 million years, now speak across the ages, reminding us of the deep continuity of life on Earth.

For the people of Syria, this fossil is also a testament to resilience. Even as the country endures hardship, its land continues to yield stories of deep time, offering knowledge that connects Syria to the broader narrative of our planet’s history.

A Legacy in Stone

The discovery of Syriemys lelunensis highlights how fossils are not only scientific data but also cultural heritage. They belong not just to paleontologists but to humanity as a whole, reminding us of the fragile yet enduring thread of life across millions of years.

In this way, the ancient turtle from Afrin has become more than a fossil. It is a messenger—connecting past to present, Syria to the wider world, and reminding us that even in moments of silence and stillness, life’s story continues to unfold beneath our feet.

More information: Wafa A. Alhalabi et al, Recovering lost time in Syria: a new Eocene stereogenyin turtle from the Aleppo Plateau, Papers in Palaeontology (2025). DOI: 10.1002/spp2.70026