Imagine standing on the shore of a shallow sea, 400 million years ago. The world looks alien, with no birdsong, no mammals, and no flowering plants. The land is barren except for the earliest pioneer vegetation—patches of mosses, lichens, and small shrubs clinging to damp sand. And in this strange silence, something remarkable happens. A fish, struggling and wriggling, pushes itself partly out of the water. Its fins dig into the sand, its snout anchors against the ground, and slowly, awkwardly, it inches forward.

These uncertain movements, recorded in stone in what is now southern Poland, capture a turning point in the history of life: the moment vertebrates began experimenting with life on land.

The Fossil Discovery in Poland

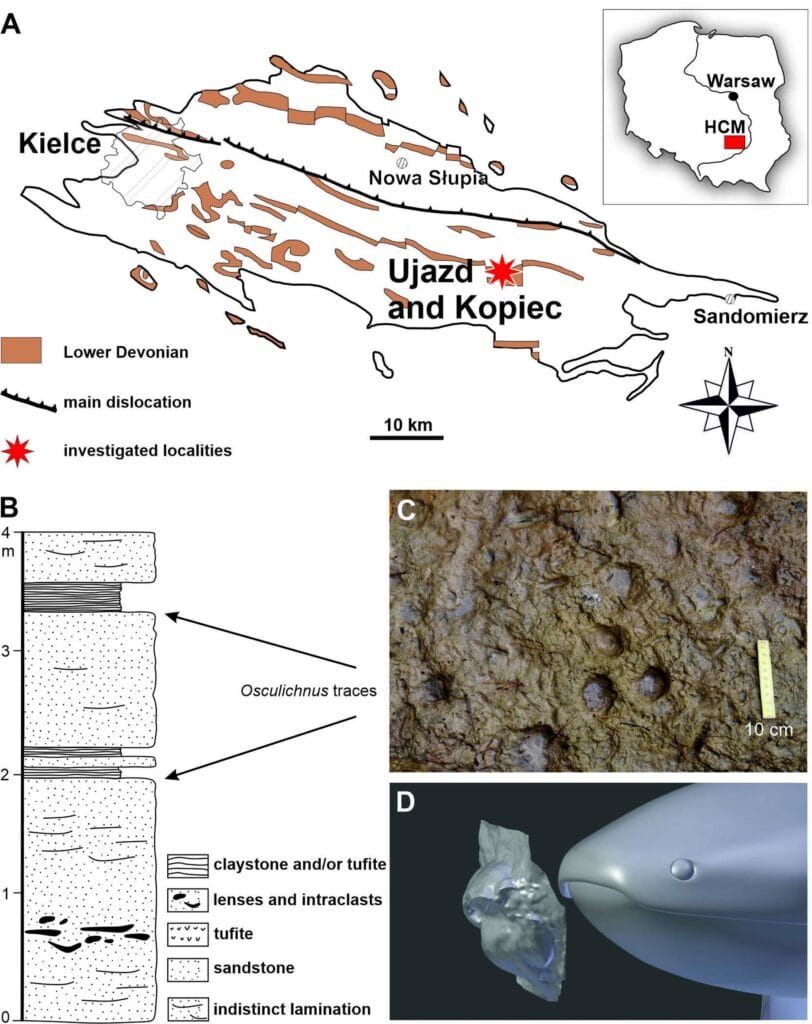

Researchers from the Polish Geological Institute–National Research Institute recently uncovered extraordinary fossilized trackways in the Holy Cross Mountains, about 190 kilometers south of Warsaw. These traces, preserved in Lower Devonian rocks dating between 419 and 393 million years ago, were left not by fully land-walking tetrapods but by their close relatives—lungfish, or dipnoans.

The trackways, protected beneath layers of volcanic ash and sandstone, reveal the marks of snouts, fins, and torsos pressed into soft sediment. Using careful excavation, high-resolution 3D scanning, and even silicone casts, scientists reconstructed how these ancient fishes moved. Their findings, published in Scientific Reports, show the oldest evidence yet of vertebrates testing their mobility on land—about ten million years earlier than previously believed.

How a Fish Leaves a Story in Stone

The quarries at Ujazd and Kopiec, where the traces were found, preserve a once coastal, marginal-marine environment. These shallow waters would periodically dry during low tide, exposing stretches of sandy flats. It was here that lungfish ventured out, leaving behind impressions of their snouts and fins as they struggled against gravity.

Some trackways record clear sequences: the fish pushing forward, its head pressed into the sediment for leverage, fins scraping as they shifted their weight. In one trace, the animal appears to have rested, leaving double pairs of furrows in the sand. Another trackway shows a consistent preference for twisting leftward, which researchers intriguingly interpret as the earliest sign of “handedness” in vertebrates.

Unlike swimming traces, which form smooth wave-like patterns, these impressions tell a story of awkward but deliberate movement on land. They reveal that fish were not only capable of surviving brief excursions out of water but also experimenting with using their bodies in ways that foreshadowed the steps of future tetrapods.

Why Would a Fish Leave the Sea?

The Devonian Period, often called the “Age of Fishes,” was a time of evolutionary experimentation. Oceans teemed with armored placoderms, sharks, and bony fish, while plants were only beginning to colonize the land. For a lungfish living in shallow waters, venturing onto damp sand may have been a matter of survival or opportunity.

During low tide, pools would shrink, oxygen levels in water would drop, and stranded animals became easy meals. By hauling themselves onto exposed flats, lungfish may have gained access to stranded prey or escaped predators. These short terrestrial forays—though temporary—represented a powerful evolutionary advantage. They were preadaptations, evolutionary rehearsals for the great invasion of land that would come millions of years later with true tetrapods.

Challenging the Timeline of Evolution

Until now, the oldest known trackways of vertebrates on land dated to the Middle Devonian, around 390 million years ago, also from the Holy Cross Mountains in Poland. The new evidence pushes that timeline back by at least ten million years, reshaping our understanding of when and how vertebrates first explored terrestrial environments.

What makes this discovery so remarkable is that it comes not from tetrapods—the four-legged vertebrates who would go on to dominate land—but from dipnoans, a sister lineage. This means that the ability to make short land excursions may not have been unique to the ancestors of amphibians, reptiles, birds, and mammals. Instead, it may have been a shared capability among multiple groups of fish experimenting with new ways of living.

A Glimpse of Ancient Behavior

The fossilized traces are more than just static marks—they are dynamic stories of behavior frozen in time. The imprints show snout anchoring, twisting movements, and the use of fins for balance, revealing how the animal interacted with its environment. They even hint at individuality: the repeated left-turning pattern suggests a consistent behavioral bias, perhaps the earliest form of “left-handedness” in the vertebrate lineage.

To capture these details, scientists used modern technology: 3D scans with micrometer precision, digital modeling, and silicone rubber casting. These tools allow paleontologists to study the subtle nuances of traces that the naked eye might miss. The result is a vivid reconstruction of how a Devonian lungfish tested the boundaries of water and land.

From Fish to Footsteps

The story of vertebrate life on land is one of the most dramatic chapters in evolution. Every step we take today is part of a lineage that began with these experimental excursions. While lungfish trackways in Poland do not represent permanent colonization of land, they do show the first sparks of possibility.

Later, in Ireland and elsewhere in Europe, more advanced tetrapods would leave behind clear footprints, evidence of efficient quadrupedal locomotion. But the Holy Cross Mountains preserve the first, uncertain trials—the splashes and wriggles of creatures still bound to water yet daring enough to touch the shore.

A Legacy Written in Stone

This discovery reminds us that evolution is rarely a single leap forward but rather a series of small, sometimes clumsy experiments. The lungfish of the Devonian could not have known that their awkward struggles across damp sand would one day give rise to animals that would walk, run, fly, and even explore space. Yet their traces remain, etched in sandstone, whispering of a time when vertebrates first tested the limits of their world.

In those faint furrows and snout marks lies the origin story of mobility on land—the first chapter of a journey that eventually produced dinosaurs, elephants, hummingbirds, and us. And all of it began with a fish daring to leave the sea.

More information: P. Szrek et al, Traces of dipnoan fish document the earliest adaptations of vertebrates to move on land, Scientific Reports (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41598-025-14541-8