Along the sunlit coast of Murcia, where dunes rise and fall under the patient shaping of wind, something unexpected has surfaced from deep time. It is not a bone or a tooth or a fragment of shell. It is movement itself, pressed into ancient sand and carried forward across 125,000 years. An international team of researchers has identified the first fossilized vertebrate footprints from the Quaternary period preserved in fossil dune deposits in this region. The marks belong to Palaeoloxodon antiquus, the straight-tusked elephant, and they tell a story that unfolds step by step, footprint by footprint.

These traces were left during the Last Interglacial, a warm interval in Earth’s past when coastal forests edged the Mediterranean and life moved freely between sea and land. The study that brings these movements back into focus is titled “New vertebrate footprint sites in the latest interglacial dune deposits on the coast of Murcia (southeast Spain). Ecological corridors for elephants in Iberia?” and it was published in the journal Quaternary Science Reviews. Within its pages lies a reconstruction of ancient journeys and a rare glimpse into Iberian paleoecology.

Following Tracks into the Last Interglacial

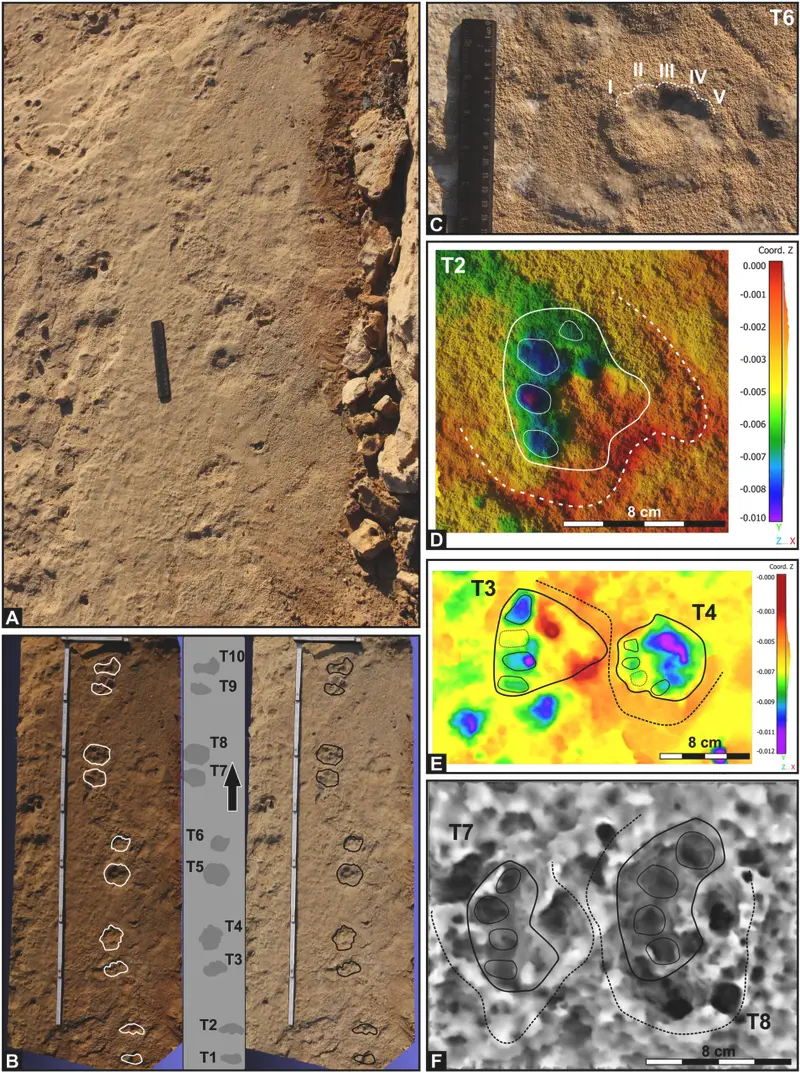

The discovery did not begin in a laboratory. It began with prospecting campaigns along the Murcian coast, in the areas of Calblanque and Torre de Cope. These surveys were coordinated by Carlos Neto de Carvalho, from the Geology Office of the Municipality of Idanha-a-Nova and the University of Lisbon. Researchers from several Spanish institutions joined the effort, including the University of Seville, the Andalusian Institute of Earth Sciences in Granada, and the University of Huelva, along with experts from Portugal.

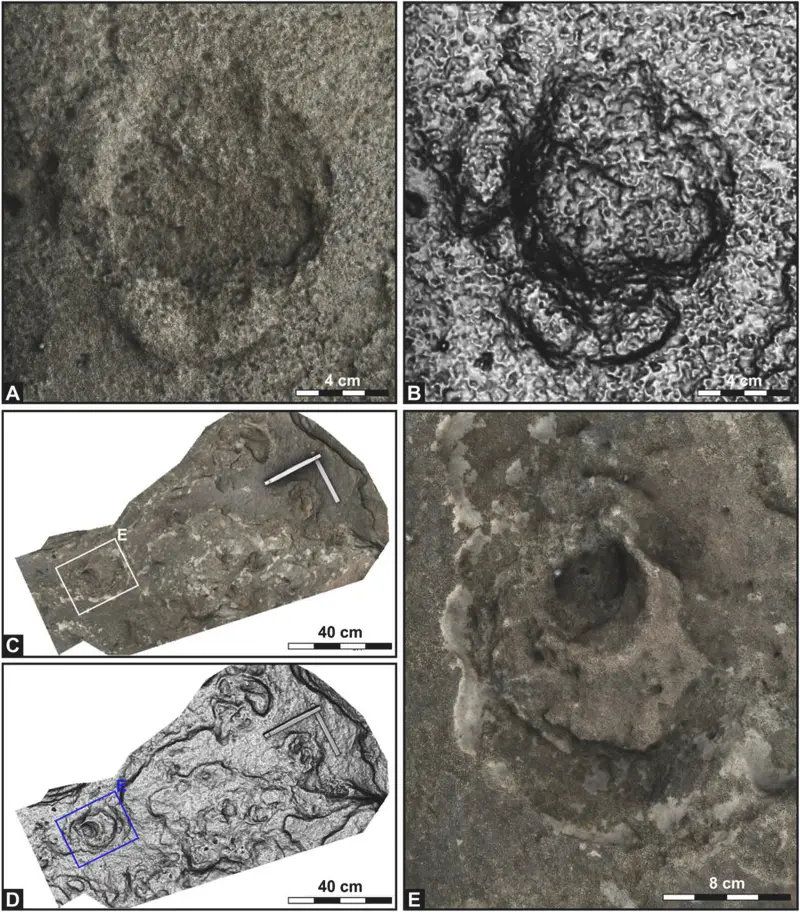

Together, they walked the dunes and fossilized sands, reading the ground as one might read a long-forgotten manuscript. What they found were four distinct areas containing fossil footprints, each offering evidence of a diverse community of mammals living in a coastal forest ecosystem during marine isotopic stage 5e. This was a time when the landscape was more humid, and when the coast acted not as a barrier but as a living corridor.

These footprints are not abstract traces. They are physical records of animals pausing, moving, and passing through. In a coastal environment where erosion and time often erase such signs, their preservation is remarkable. Each print anchors a moment, fixing it in space and time.

The Elephant Who Crossed the Dunes

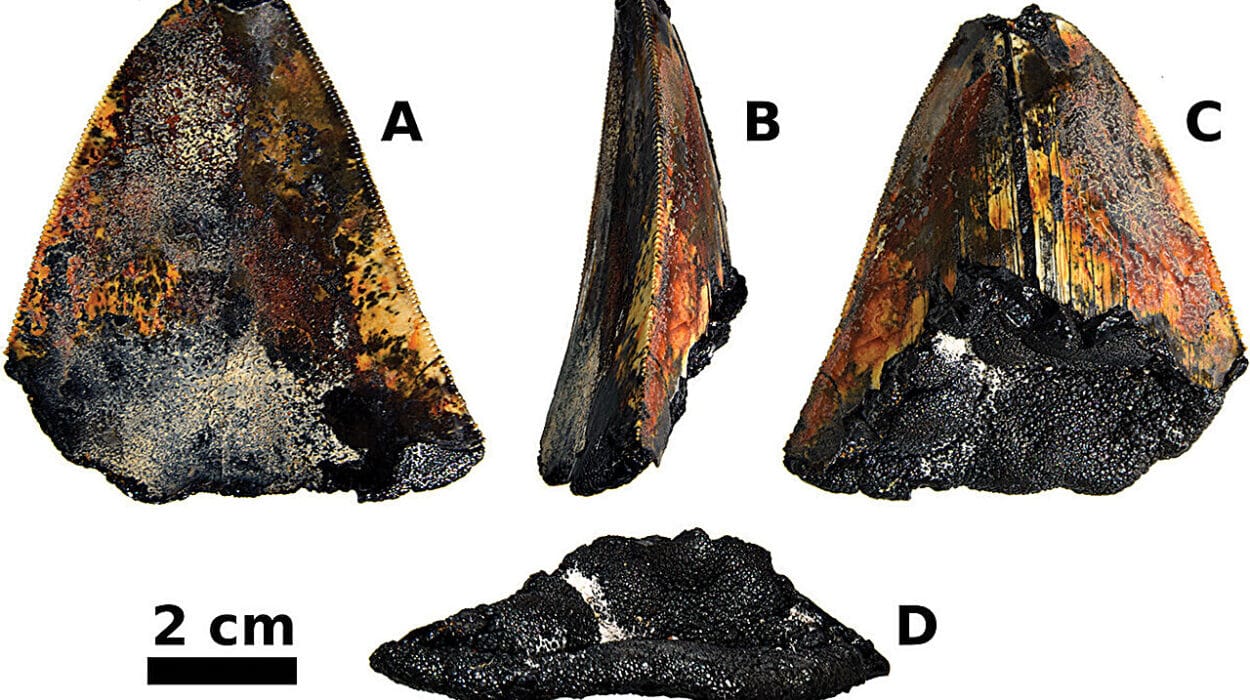

The most striking discovery lies at Torre de Cope. Here, preserved in fossil dune deposits, is a proboscidean trackway stretching 2.75 meters. It consists of four rounded footprints, each measuring between 40 and 50 centimeters in diameter. Their arrangement is unmistakable, forming a pattern typical of the quadrupedal gait of elephants.

From this pattern, researchers were able to do more than simply identify the species. They reconstructed the animal itself. The trackway belonged to an adult Palaeoloxodon antiquus, standing about 2.3 meters tall at the hip, over 30 years old, and weighing approximately 2.6 tonnes. These estimates transform footprints into presence. Suddenly, the elephant is no longer an abstract megafaunal concept but a living being moving deliberately across coastal dunes.

This straight-tusked elephant was not wandering aimlessly. Its path speaks of direction and purpose, suggesting that the coast was part of a broader movement route. The dunes, now silent, once bore the weight of giants.

Smaller Lives in the Same Sand

The elephant was not alone. In Calblanque, the fossil record reveals traces of much smaller creatures, adding layers to the ancient ecosystem. One trail belongs to a medium-sized mustelid. It stretches one and a half meters and is made up of ten almost circular footprints arranged in pairs. The pattern suggests slow movement, likely near water sources, hinting at cautious behavior in a resource-rich environment.

Nearby, an isolated footprint tells another story. Measuring 10 by 8 centimeters and marked with claw impressions, it points to the presence of a canid. The researchers interpret this as evidence of predators such as wolves, specifically Canis lupus, inhabiting wooded habitats along the coast. Even a single print can speak volumes, suggesting alertness, territory, and the balance between hunter and hunted.

The sand also preserves bifid footprints up to 10 centimeters in size, compatible with red deer, Cervus elaphus. These prints show a westward orientation, indicating movement through dunes and scrubland. They suggest herds navigating the landscape, perhaps following seasonal rhythms or seeking food and shelter.

Another trail belongs to a young equid, Equus ferus. Its footprints measure approximately 10 by 12 centimeters. This find represents the most recent record of this species in the south-east of the Iberian Peninsula. It adds yet another voice to the chorus of life that once moved through these coastal corridors.

A Living Corridor Between Forest and Sea

When viewed together, these footprints do more than catalogue species. They form a pattern of movement that supports a broader hypothesis. The data suggest the existence of coastal ecological corridors used for seasonal migrations. These corridors would have connected Mediterranean forests with beaches, creating pathways through a landscape that was wetter and more hospitable than today’s.

Such corridors would have allowed megafauna like elephants to move across Iberia, following resources and climate conditions. At the same time, smaller mammals and predators shared these routes, weaving a complex web of ecological interactions. The coast was not merely a boundary between land and sea; it was a lifeline.

This perspective reshapes how we imagine the Pleistocene landscape of southeastern Iberia. Instead of isolated habitats, we see connected environments where movement was essential to survival.

Where Elephants and Humans Shared the Coast

The implications of these findings reach beyond animal ecology. They open a window onto human history as well. In examining these coastal corridors, the researchers draw a connection to paleoanthropology, noting a geographical coincidence between the routes followed by elephants in south-eastern Iberia and sites with Neanderthal presence.

During the Pleistocene, the Iberian Peninsula would have acted as a climate refuge for both fauna and flora. It also served as a route for large mammals, including elephants. Where elephants went, resources followed. And where resources were abundant, Neanderthals could thrive.

These coastal areas would have been rich landscapes, offering opportunities for hunting and subsistence. The overlap between megafaunal pathways and Neanderthal sites suggests that humans were not random occupants of the land. They were attentive observers, living within and responding to the same ecological corridors traced by animals.

Why These Ancient Steps Matter Today

The fossilized footprints of Murcia matter because they preserve motion, not just form. Bones tell us what an animal was. Footprints tell us what it did, where it went, and how it interacted with its environment. In a few impressions of ancient sand, we glimpse entire ecosystems in motion.

This research enriches our understanding of Iberian paleoecology by showing how coastal landscapes functioned as dynamic corridors during the Last Interglacial. It highlights the role of the Iberian Peninsula as both refuge and crossroads, shaping the lives of megafauna and humans alike. By linking elephant migration routes with Neanderthal presence, the study bridges ecology and anthropology, reminding us that human history is inseparable from the movements of other species.

Most of all, these discoveries matter because they show how much information can still lie hidden beneath our feet. A dune is not just sand shaped by wind. It can be a page from Earth’s memory, waiting to be read. When we learn to read it carefully, we do not just uncover the past. We gain insight into how landscapes, animals, and humans are woven together across time, and how movement itself leaves traces that can endure for tens of thousands of years.

More information: Carlos Neto de Carvalho et al, New vertebrate tracksites from the Last Interglacial dune deposits of coastal Murcia (southeastern Spain): ecological corridors for elephants in Iberia?, Quaternary Science Reviews (2025). DOI: 10.1016/j.quascirev.2025.109631