It begins with fragments. Not a complete skull resting in a museum drawer, but scattered pieces of bone pulled from ancient ground, carrying the quiet weight of more than a million years. At the site of Gona in Ethiopia’s Afar region, scientists once uncovered such fragments during fieldwork in 2000. For years, those pieces hinted at a story they could not yet fully tell.

Now, that story has a face.

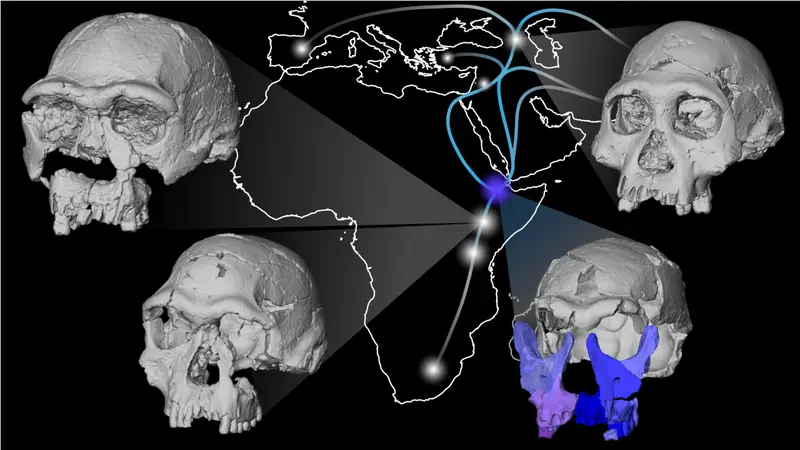

An international team of researchers, led by Dr. Karen Baab, a paleoanthropologist at the College of Graduate Studies, Glendale Campus of Midwestern University in Arizona, has produced a virtual reconstruction of an early Homo erectus individual known as DAN5. The fossil dates to between 1.5 and 1.6 million years ago, a time when early humans were spreading across continents and redefining what it meant to be human.

The reconstruction, published in Nature Communications, brings into view a surprisingly archaic face. It is not merely a technical achievement. It is a moment of recognition across time, revealing new clues about who Homo erectus was and how our ancestors changed, migrated, and endured.

Gona, Where Human History Runs Deep

Gona is not an ordinary fossil site. Co-directed by Dr. Sileshi Semaw and Dr. Michael Rogers, the Gona Paleoanthropological Research Project has uncovered hominin fossils older than 6.3 million years and stone tools spanning the last 2.6 million years of human evolution. The land itself seems to remember every chapter.

The fossil known as DAN5 belongs to this extraordinary archive. It consists of a braincase, described previously in 2020, along with smaller fragments of the face and teeth. All of these remains come from a single individual who lived during a crucial period in human evolution, after Homo erectus had begun to spread widely across Africa, Asia, and Europe.

Until now, those facial fragments could not speak clearly. They were too incomplete, too separated by time and damage. But technology offered a way to listen more closely.

A Year Spent Solving a Puzzle Without a Picture

Reconstructing DAN5 was not a matter of guesswork or artistic imagination. It was a careful, methodical process grounded in anatomy and digital precision. The researchers began by using high-resolution micro-CT scans on four major fragments of the face. From these scans, they created detailed 3D models.

On a computer screen, the fragments were slowly brought together. Teeth were fitted into the upper jaw wherever possible. The final and most delicate step was attaching the reconstructed face to the fossil braincase, creating a mostly complete cranium.

This work took about a year and went through several iterations before reaching its final form. Dr. Baab, who carried out the reconstruction, described the process as “a very complicated 3D puzzle, and one where you do not know the exact outcome in advance. Fortunately, we do know how faces fit together in general, so we were not starting from scratch.”

When the pieces finally aligned, something unexpected appeared.

An Archaic Face Looking Back

The reconstructed face of DAN5 did not look like what scientists anticipated for an African Homo erectus of this age. The braincase showed traits typical of the species, but the face and teeth told a different story. They appeared more primitive, resembling features usually associated with earlier hominin species.

Dr. Baab explained the surprise clearly: “We already knew that the DAN5 fossil had a small brain, but this new reconstruction shows that the face is also more primitive than classic African Homo erectus of the same antiquity. One explanation is that the Gona population retained the anatomy of the population that originally migrated out of Africa approximately 300,000 years earlier.”

The bridge of the nose is notably flat. The molars are large. These ancestral traits contrast with what scientists expected to see at this point in Homo erectus evolution.

For one of the study’s co-authors, the emotional impact was immediate. “I’ll never forget the shock I felt when Dr. Baab first showed me the reconstructed face and jaw,” says Dr. Yousuke Kaifu of the University of Tokyo.

Challenging Old Ideas About Where Homo erectus Evolved

To understand what this face meant, scientists compared the size and shape of the DAN5 face and teeth with fossils from the same geological age, as well as with older and younger specimens. Similar combinations of traits had been documented in Eurasia before, but never inside Africa.

This matters because it complicates long-standing ideas about human evolution. The presence of both derived Homo erectus features and ancestral facial traits in Africa challenges the notion that these transitional forms evolved only outside the continent.

“The oldest fossils belonging to Homo erectus are from Africa, and the new fossil reconstruction shows that transitional fossils also existed there, so it makes sense that this species emerged on the African continent,” says Dr. Baab. “But the DAN5 fossil postdates the initial exit from Africa, so other interpretations are possible.”

The face of DAN5 does not deliver a simple answer. Instead, it opens multiple paths of interpretation, each pointing to a more complex evolutionary landscape than previously imagined.

A Species Rich in Variation

Rather than fitting neatly into a single evolutionary line, Homo erectus appears increasingly diverse. DAN5 reinforces this picture, showing that early members of our genus did not all look or develop the same way at the same time.

Dr. Rogers sees this diversity as a central lesson of the find. “This newly reconstructed cranium further emphasizes the anatomical diversity seen in early members of our genus, which is only likely to increase with future discoveries.”

DAN5 also carries cultural significance. According to Dr. Semaw, this individual was making both simple Oldowan stone tools and early Acheulian handaxes. “It is remarkable that the DAN5 Homo erectus was making both simple Oldowan stone tools and early Acheulian handaxes, among the earliest evidence for the two stone tool traditions to be found directly associated with a hominin fossil,” he adds.

This pairing of anatomical diversity and technological flexibility paints a picture of early humans who were adaptable, inventive, and far from uniform.

Looking Ahead Across Continents and Species

The story of DAN5 is not finished. Researchers hope to compare this fossil with some of the earliest human fossils from Europe, including those assigned to Homo erectus and a distinct species known as Homo antecessor, dated to about one million years ago.

“Comparing DAN5 to these fossils will not only deepen our understanding of facial variability within Homo erectus but also shed light on how the species adapted and evolved,” explains Dr. Sarah Freidline of the University of Central Florida.

There is also room to explore alternative evolutionary scenarios. One possibility is genetic admixture between different hominin species, similar to patterns seen later among Neanderthals, modern humans, and Denisovans. In this view, DAN5 might represent a blending of classic African Homo erectus with an earlier species such as Homo habilis.

For now, these ideas remain hypotheses awaiting more evidence. As Dr. Rogers puts it, “We’re going to need several more fossils dated between one to two million years ago to sort this out.”

Why This Face Matters

The reconstructed face of DAN5 is more than a scientific achievement. It is a reminder that human evolution is not a straight line but a branching, overlapping story filled with variation and surprise. By revealing a mix of ancestral and derived traits in a single individual, this research challenges simplified narratives about where and how Homo erectus evolved.

It shows that Africa was not only the birthplace of our species but also a place of ongoing experimentation, where different populations carried different combinations of features through time. It reminds us that migration did not erase diversity, and that evolution often preserves old traits alongside new ones.

Most of all, the face of DAN5 brings us closer to understanding ourselves. It allows us to look into the deep past and see a human ancestor not as a vague idea, but as an individual shaped by history, environment, and chance. In doing so, it deepens our appreciation of the complex journey that led to us, and underscores how much of that journey remains waiting beneath the ground, ready to be uncovered.

More information: Karen L. Baab et al, New reconstruction of DAN5 cranium (Gona, Ethiopia) supports complex emergence of Homo erectus, Nature Communications (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-66381-9