It was a moment of sheer wonder, the kind that science gifts only occasionally—a brief flicker of ancient life reawakened by the glow of robotic lights. Deep beneath the surface of the Pacific Ocean, far from the nearest shore and deeper still from the reach of casual discovery, a lone, fossilized tooth stood silently in the sand. Not in a museum drawer, not in a child’s collection on a beach, but still embedded in the place where it had fallen millions of years ago—from the mouth of a predator that once ruled the seas.

The discovery wasn’t planned. In fact, it was accidental. A team of oceanographers aboard a research vessel, conducting a deep-sea survey near Johnston Atoll, had deployed a remotely operated vehicle (ROV) to inspect the topography of the ocean floor. What they found was something no one had seen before: a fossilized tooth belonging to Otodus megalodon, the most formidable marine predator to ever swim Earth’s oceans—lying perfectly upright, as if time itself had simply forgotten to move it.

Echoes from a Prehistoric Hunter

The megalodon, whose name literally means “giant tooth,” is one of paleontology’s most fascinating and terrifying enigmas. Roaming the seas between 3.6 and 23 million years ago, this extinct species of megatooth shark is believed to have reached lengths of 50 to 60 feet—roughly the size of a city bus. Its jaws could crush the bones of whales. Its presence in the Miocene oceans shaped marine ecosystems with a dominance that was unrivaled.

Yet, for all its size and strength, the megalodon left behind remarkably little physical evidence. Its skeleton, made primarily of cartilage, degraded long ago. What remains are its teeth—tens of thousands of them, scattered across the planet’s beaches, riverbeds, and fossil deposits. Most are found far from where they fell, tumbled by water and time, worn smooth by erosion, and buried deep in sediment.

But this newly found specimen is different. This tooth did not wander. It landed, and there it stayed—for possibly millions of years—embedded in the seabed like a memorial to a vanished world.

Discovery in the Midnight Zone

The waters surrounding Johnston Atoll are not the sort of place one stumbles upon ancient relics. This isolated stretch of the Pacific, located over 700 miles from the nearest Hawaiian island, lies above a sea floor so deep and remote that few instruments have ever touched it. The region is part of the “midnight zone”—a layer of the ocean where sunlight cannot reach and life assumes strange and fascinating forms.

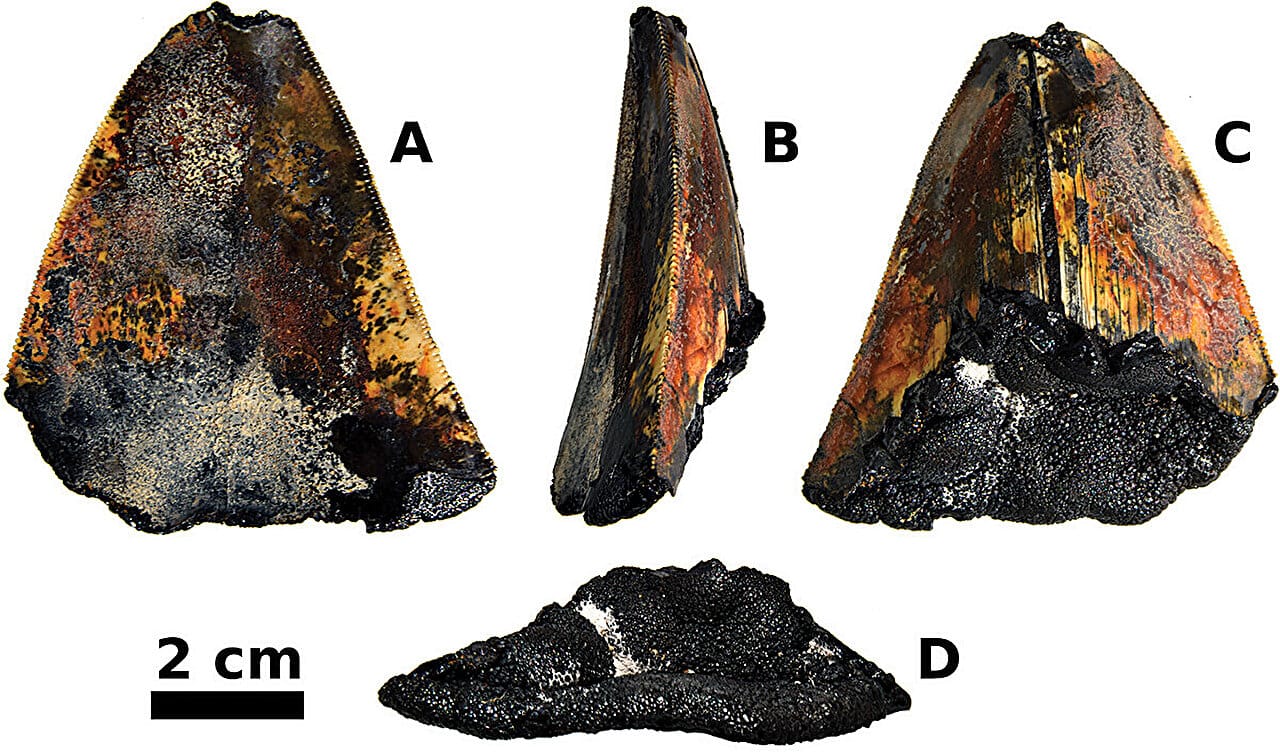

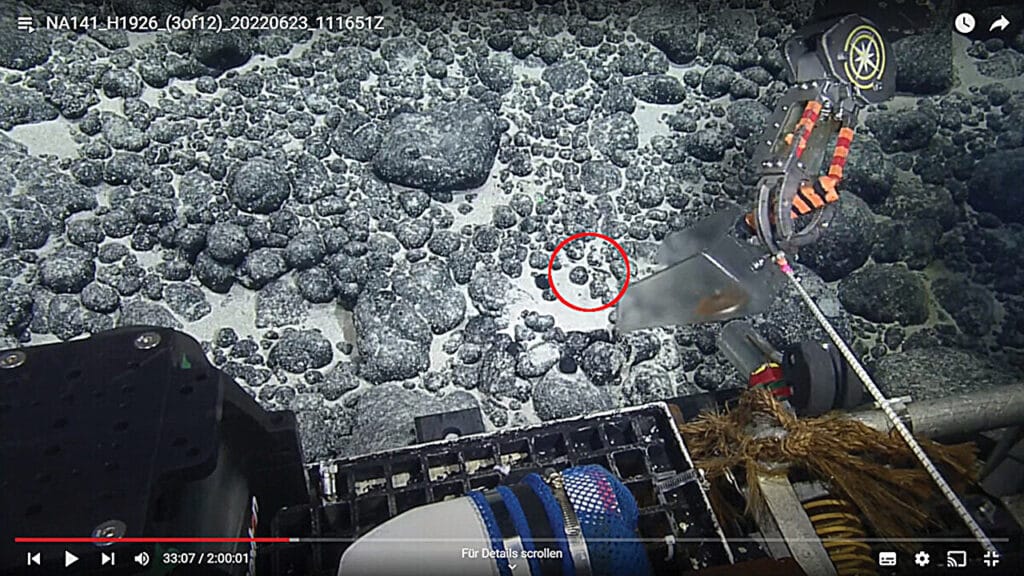

It was here, in the shadowy depths, that the ROV’s cameras captured the unmistakable triangular silhouette of the tooth, partially buried in pale sediment but still strikingly prominent. Its serrated edges—used once to rip through thick whale blubber—remained sharp. The color was dull but rich with time, shaded in hues of grey and brown. The tooth was estimated to measure just over 6 centimeters long, suggesting it had belonged to a younger or smaller megalodon—still enormous by modern standards.

This was not just a fossil. It was a direct window into a moment lost to history.

Why This Tooth Matters

Unlike teeth found on beaches or dug from rocky cliffs, this specimen was discovered in situ—in the exact place it landed after falling from the jaws of its owner. It had not been dragged by currents, cracked by rocks, or buried under layers of sediment. The preservation was startling. The surrounding seabed, rather than covering the tooth with time, had remained relatively static due to the peculiar nature of the ocean currents in the area. Instead of being eroded by movement, the tooth was essentially locked in stasis, protected by the dynamic flow that constantly swept finer sediments away.

This exceptional preservation allowed researchers to examine not just the tooth’s structure, but its precise orientation and condition, giving them clues about how these fossilized remains might behave in the deep sea over millions of years. For the first time, scientists could study a megalodon tooth exactly as it had fallen, offering insight into decay rates, fossil stability, and the role ocean floor dynamics play in preserving prehistoric material.

The discovery brings forth a deeper understanding of how fossils behave in extreme environments. It confirms that under the right conditions, even fragile relics can survive the slow crush of time—untouched and unburied, waiting for the world to notice.

Chasing Shadows in a Sunless World

The ROV’s footage shows the tooth surrounded by a desolate, almost alien landscape. The floor is mostly flat, occasionally interrupted by small rises, pockmarks, and curious textures left by benthic animals. There are no schools of fish, no coral fans, no movement beyond the ROV’s own mechanical limbs. It’s a realm few would associate with Earth at all—yet here lies a remnant of the planet’s most terrifying carnivore, half a world away from the sunlit shallows where megalodons are thought to have hunted.

This raises questions about the megalodon’s final journeys. Could this tooth’s presence at such a depth suggest that megalodons roamed further or deeper than previously believed? Or was this tooth simply carried downward by a dying shark, drifting into the abyss like a ghost ship?

Oceanographers can’t say for sure. But the discovery does hint at a more complex life history for the species. Teeth found in coastal deposits tell one story—of feeding grounds and nursery zones. A tooth found alone in the open deep sea might tell another. It could indicate predatory excursions into deeper waters, scavenging behavior, or even something about where these giants came to die.

Each possibility adds a layer of nuance to our understanding of the creature that once ruled the oceans.

A Tooth, a Timeline, and a Tantalizing Clue

The fossilized tooth retrieved from the seafloor was dated by context rather than absolute methods, but it likely falls into the latter part of the megalodon’s reign—perhaps around 5 million years ago. During that time, Earth was cooling, sea levels were shifting, and marine ecosystems were changing in ways that would eventually spell the end for apex predators like the megalodon.

The sharp, undamaged serrations on the tooth suggest minimal abrasion. It didn’t tumble through rocks or crash against coral. Instead, it fell, point-down into soft sediment, where it stayed—resisting time in a way that almost feels defiant.

Such a pristine fossil in its original position is a rare gift to science. It offers a reference point against which all future discoveries might be measured. Its placement, structure, and even micro-wear patterns could help paleontologists distinguish between teeth that moved and those that didn’t—between fossils shaped by Earth’s shifting surface and those left untouched.

In essence, this one tooth is now a calibration point in the timeline of megalodon science.

Beyond Teeth: The Future of Deep-Sea Paleontology

For centuries, paleontology has been a science of dry land. Fossils are chiseled from rock faces, extracted from hillsides, or lifted from the beds of ancient rivers. But the oceans—covering more than 70% of Earth’s surface—have only begun to reveal their secrets.

This discovery marks a turning point. It shows that the deep sea, long thought too dynamic or destructive to preserve delicate fossils, may in fact hold treasures that rival even the richest terrestrial sites. And it highlights the role technology will play—remotely operated vehicles, advanced imaging tools, and collaborative missions that blend marine science with evolutionary biology.

In the coming decades, oceanographers and paleontologists may find more than just teeth. Bones, cartilage impressions, and ancient sediment layers could yield not only more data, but the stories of lives that ended miles beneath the waves.

What other fossils lie in wait, tucked into underwater ravines and ridges? What chapters of prehistoric life remain unwritten, simply because we haven’t yet looked in the right place?

A Message from the Deep

The megalodon’s extinction was final, but its legacy is still being uncovered—one tooth at a time. And sometimes, as in this case, the ocean offers that legacy back to us in perfect silence.

There are no dramatic endings in science—only new beginnings. This tooth, rising from the sea floor after eons of rest, is more than a fossil. It is a message. A reminder that Earth’s history is vast, its memory long, and its stories still waiting to be heard beneath the waves.

As our tools grow more sophisticated and our curiosity more ambitious, we may continue to unearth wonders like this—moments where the ancient world reaches across time and touches our own.

And who knows? The next light to shine on a forgotten corner of the sea floor may reveal not just a tooth, but the beginning of a new chapter in the story of life on Earth.

Reference: Jürgen Pollerspöck et al, First in situ documentation of a fossil tooth of the megatooth shark Otodus ( Megaselachus ) megalodon from the deep sea in the Pacific Ocean, Historical Biology (2023). DOI: 10.1080/08912963.2023.2291771