In the sweeping silence of Australia’s sun-scorched deserts and dense eucalyptus forests, the goanna—a reptilian relic with dagger claws and flickering tongue—prowls like a shadow of the prehistoric past. For millennia, these monitor lizards have captivated Indigenous lore and modern science alike, their presence etched into the soul of the continent. But now, beneath their coarse, scale-covered skin, scientists have uncovered a secret that was hiding in plain sight: a microscopic mosaic of bone embedded within their flesh—osteoderms, ancient armor that may rewrite our understanding of reptilian evolution.

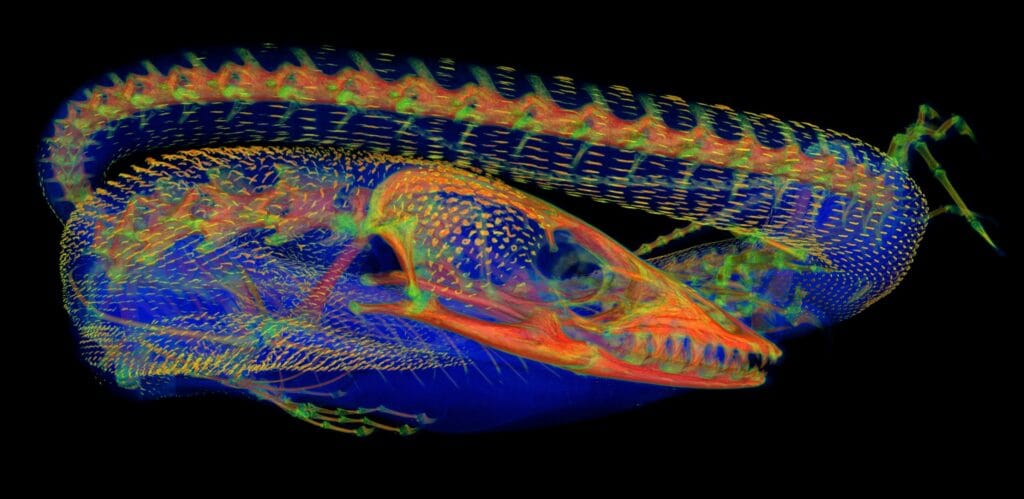

This remarkable discovery, published in the Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, sheds light not only on the biology of these iconic lizards but on the broader evolutionary history of reptiles across the globe. Through cutting-edge micro-CT imaging and a massive collaborative effort spanning continents, researchers have revealed that bony skin structures—once thought rare in lizards—are astonishingly widespread. The implications reach far beyond the dry heart of Australia, touching on the very nature of survival, adaptation, and resilience in some of Earth’s most extreme environments.

Bones Beneath the Skin: An Evolutionary Puzzle Unearthed

Osteoderms—small, calcified plates embedded in the skin—are not a new concept in biology. They are familiar to us in creatures such as crocodiles, armadillos, and extinct behemoths like Stegosaurus. These dermal bones are usually assumed to serve as armor, a natural defense system forged by evolution against tooth and claw. But their exact purpose remains elusive, particularly in species that don’t face constant predatory threat.

In lizards, osteoderms were long considered relatively rare and limited to a handful of species. That assumption has now been thoroughly dismantled.

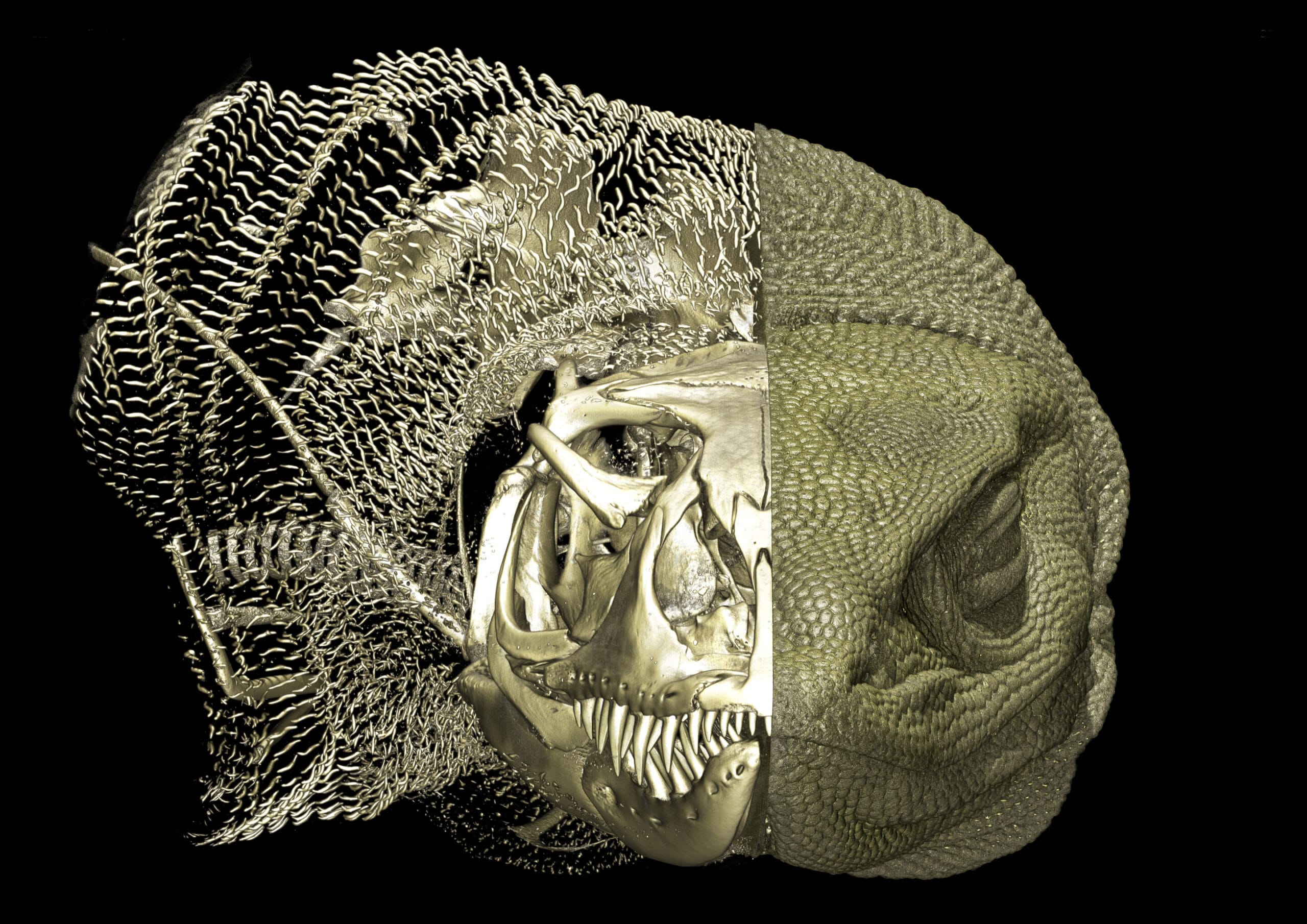

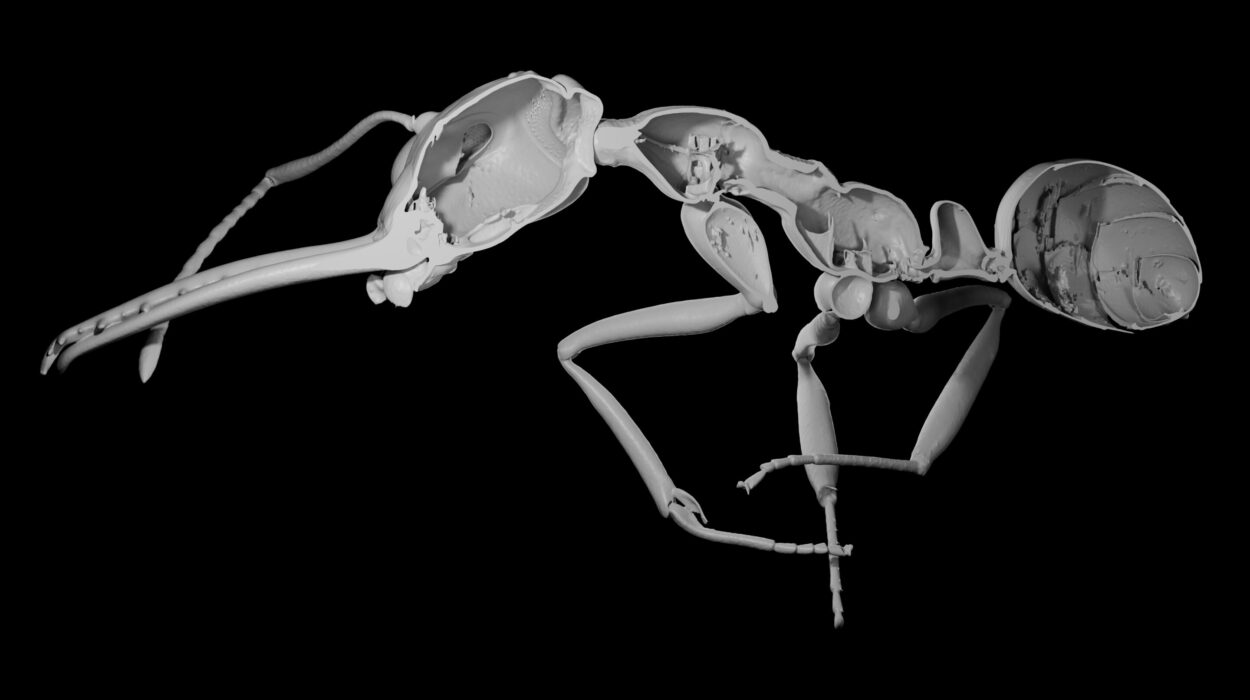

In the new study, researchers examined nearly 2,000 specimens from global museum collections, including those held at the Museums Victoria Research Institute in Australia. Using micro-computed tomography (micro-CT), a scanning technology that enables three-dimensional imaging of internal structures at microscopic resolution, the team uncovered osteoderms in 29 species of Australo-Papuan monitor lizards—commonly known as goannas—where none had previously been documented.

“We were astonished,” said Roy Ebel, lead author of the study and a researcher at both Museums Victoria Research Institute and the Australian National University. “This is a fivefold increase in the known number of goanna species with osteoderms. It changes everything we thought we knew about their anatomy.”

More Than Just Armor: A Multifunctional Marvel

The revelation that osteoderms are so widespread—found in nearly half of all lizard species worldwide, marking an 85% increase over previous estimates—forces a reexamination of their evolutionary role. Were they always just a defense against predators, or did they evolve under more complex pressures?

Modern theories suggest that osteoderms may be multifunctional. While their protective role is undeniable—forming a kind of internal chainmail that absorbs impacts—some researchers now believe that these bony plates may help with thermoregulation, storing and releasing heat like natural radiators. Others propose that they act as internal calcium reservoirs, especially important for females during reproduction when calcium demand spikes for eggshell production. Still others hypothesize that they play a biomechanical role, providing structural support and aiding locomotion.

“These aren’t just inert pieces of bone,” explained Dr. Jane Melville, Senior Curator of Terrestrial Vertebrates at Museums Victoria. “They’re living tissues, with potential physiological functions that could explain why they’re so widespread in harsh and variable environments like Australia.”

Australia’s Harsh Beauty: A Catalyst for Evolution

Australia is a continent of extremes. Its vast interior deserts pulse with blistering heat by day and freezing temperatures by night. In the north, monsoons drench rainforests in seasonal torrents. Food and water are often scarce, and survival is a balancing act between endurance and adaptation.

It is in these crucibles of climate that the goannas have evolved into some of the most successful and ecologically versatile predators on the continent. The presence of osteoderms across so many species suggests that these internal armor plates may have played a critical role in their success.

The idea is compelling: as environmental stressors intensified over millennia, certain physiological features—like osteoderms—may have conferred a survival advantage, enabling monitor lizards to flourish where others faltered. The evolution of these dermal bones, once perhaps incidental, may have become essential in a land where adaptability is the currency of life.

Ancient Specimens, New Technologies: Museums as Time Machines

At the heart of this breakthrough lies the often underappreciated role of natural history museums. Many of the specimens used in this study had been collected decades ago—some over a century old—and preserved in drawers and jars across institutions in Australia, Europe, and the United States. Yet thanks to recent advances in non-destructive imaging, particularly micro-CT scanning, researchers were able to peer into these ancient bodies without damaging them.

Each scan is like an x-ray for time itself, revealing hidden layers of anatomy that previous generations of scientists could never have imagined. The quiet patience of curators and collectors—those who gathered and preserved these specimens over the last 120 years—has suddenly become an active force in shaping 21st-century science.

“These collections are not just dusty archives,” said Melville. “They are living libraries of biodiversity. Every specimen has more to tell us than we ever dreamed, and with the right tools, we’re finally learning to listen.”

Goannas Reimagined: More Than Just Scaled Predators

For many Australians, goannas are a familiar sight—darting across country roads, basking on sun-drenched rocks, or climbing trees with unsettling grace. They occupy a unique space in cultural consciousness, celebrated in Aboriginal mythology and feared in rural folklore. Yet beneath their charismatic exteriors lies a deeper story, now only coming into focus.

Until recently, the only monitor lizard species in which osteoderms were well-documented was the Komodo dragon of Indonesia—a hulking predator known for its venomous bite and armored hide. The assumption was that such features were rare among the monitor family. But the new findings reveal a startling reality: that goannas across Australasia are far more heavily “armored” than anyone realized.

This doesn’t just revise our anatomical knowledge—it demands a rethinking of how we understand the evolutionary journey of these reptiles. Were osteoderms a retained ancestral trait from distant prehistoric relatives? Or did they evolve independently in response to the unique challenges of the Australo-Papuan region?

The answers may lie deep in evolutionary history, in the fossil record yet to be uncovered, or in further micro-CT scans waiting to be conducted. But one thing is certain: our models of reptile evolution just became much more complex—and infinitely more fascinating.

The Interplay of Skin, Structure, and Survival

The implications of this research stretch far beyond goannas. By revealing the true extent and variability of osteoderms in reptiles, scientists are now equipped with an entirely new dataset for examining how skin, bone, and environment interact over evolutionary timescales.

This knowledge could inform fields ranging from biomechanics and climate adaptation to conservation biology and developmental genetics. It might help scientists predict how modern reptiles will respond to changing climates, or provide insights into how ancient creatures coped with environmental upheaval.

In this interplay of biology and geology, skin and stone, function and form, lies one of the most profound truths of life on Earth: that survival is written into the body, and evolution leaves its signature in the bones.

Conclusion: Secrets Etched in Bone

What began as an exploration of museum collections has blossomed into a revelation about life itself. Hidden beneath the tough exterior of Australia’s monitor lizards, in the microscopic latticework of their skin, is a story of resilience, adaptation, and deep-time survival.

These goannas, once thought to be mere remnants of a primitive past, now stand as ambassadors of evolutionary sophistication. With each CT scan, with each cross-section of tissue and time, we peel back the layers of ignorance and inch closer to understanding the miraculous tapestry of life.

In the end, the osteoderms are more than bones beneath skin. They are whispers from ancient ancestors, a legacy of natural engineering honed across epochs. They remind us that even in the most familiar of creatures, the extraordinary often lies just beneath the surface—waiting to be seen.

Reference: Roy Ebel et al, Dermal armour in lizards: Osteoderms more common than presumed, Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society (2025). DOI: 10.1093/zoolinnean/zlaf070