When University of Arizona geologist and archaeologist Vance Holliday first stepped onto the otherworldly landscape of White Sands, New Mexico in 2012, he expected to examine sediment layers and piece together geological history. What he didn’t expect was to stand mere steps away from one of the most controversial and revolutionary discoveries in American archaeology—footprints, buried in ancient clay, that might just rewrite the story of how humans first came to the continent.

“It’s surreal out there,” Holliday recalled. “You’re surrounded by nothing but white dunes made of gypsum, and beneath your feet is a frozen moment from 23,000 years ago.”

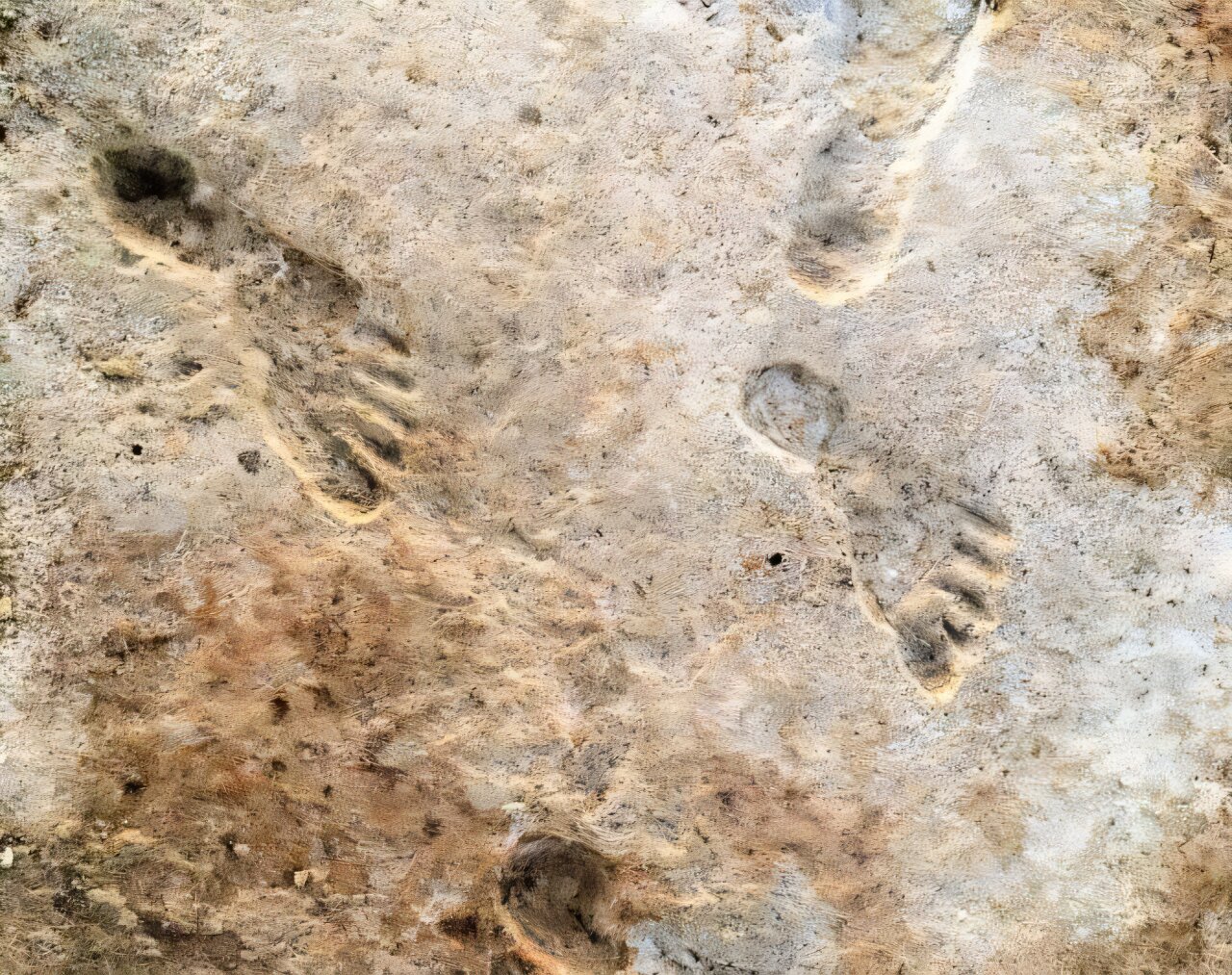

These are not just any footprints. Preserved in what was once the muddy shoreline of a long-vanished lake, the tracks belong to early humans who left them behind as they walked through the Pleistocene world—millennia before the Clovis culture, long considered the earliest known civilization in North America, ever left a trace.

The first study that dated the footprints to between 21,000 and 23,000 years ago was published in 2021 and sparked a firestorm of debate in the archaeological community. Critics questioned the reliability of the materials used to date the tracks—namely ancient seeds and pollen. Could such fragile remnants really anchor a claim that rewrote tens of thousands of years of human history?

Now, Holliday and his team have returned with a new study, published in Science Advances, that strengthens the evidence. This time, the age of the footprints was confirmed using a different material altogether: ancient mud.

Ghosts on the Shoreline of an Ancient Lake

To truly understand the magnitude of this discovery, one must imagine White Sands not as it is today—bleached and windswept—but as it was over 20,000 years ago. Back then, the region was a series of shallow lakes, surrounded by grassy plains where mammoths, giant ground sloths, and early humans coexisted.

The footprints were discovered in the dried streambeds that once fed one of these ancient lakes. They tell a story of brief, fleeting movement—some trackways would’ve taken just seconds to walk. But they are clear, unmistakable impressions left behind by barefoot humans.

“You look at them and realize someone walked here tens of thousands of years ago,” said Jason Windingstad, a doctoral candidate in environmental science who co-authored the latest study. “It completely contradicts everything you’re taught about when humans arrived in North America.”

For decades, archaeologists believed the first humans reached the continent around 13,000 years ago, based on tools and remains found near Clovis, New Mexico. The so-called Clovis culture became the benchmark for human presence in the Americas. But these footprints—if dated correctly—predate Clovis by nearly 10,000 years.

The Debate Over Dates

The original study in 2021 ignited debate not because the tracks were doubted—they are remarkably well-preserved—but because of how they were dated. Researchers had used ancient plant material—seeds and pollen—found in the same layers as the footprints to estimate their age.

Skeptics argued those materials could have been contaminated or displaced over the centuries. Dating sedimentary material is notoriously difficult, and without consensus on the reliability of the dating process, the discovery hung in limbo, a scientific mystery waiting for corroboration.

Now, with the new study, the timeline is reinforced with fresh evidence. Holliday and Windingstad returned to White Sands in 2022 and 2023 to extract samples of ancient mud. These were sent to an independent laboratory for radiocarbon dating—marking the third type of material (alongside seeds and pollen) and the third lab to verify the age of the footprints.

The results: the mud is between 20,700 and 22,400 years old, a near-perfect match for the 2021 data.

“You get to the point where it’s really hard to explain all this away,” Holliday said. “To have three different materials dated, by three labs, with 55 radiocarbon samples, all giving you the same range—that’s not coincidence. That’s confirmation.”

Missing Artifacts and Elusive Evidence

Still, not everyone is convinced. One lingering question remains: Where are the tools? The campsites? The bones and fire pits that typically accompany human presence?

It’s a question Holliday doesn’t shy away from.

“These people were hunter-gatherers, likely very careful with their resources,” he said. “If you’re far from a source of replacement materials, you’re not going to casually discard tools.”

Many of the footprints were part of short trackways, suggesting momentary travel—not long-term habitation. Holliday believes that expecting a debris field near such fleeting activity is unrealistic.

“They weren’t living there. They were passing through,” he said. “And the rest of their story is buried under the world’s largest gypsum dune field.”

Indeed, wind erosion over millennia has both preserved and destroyed the evidence. While the footprints remained protected beneath layers of sediment, other parts of the ancient landscape have been lost to time. What remains is precious and fragile—a rare glimpse into lives that played out on the shorelines of a vanished world.

A Turning Point in the Human Timeline

If the data continues to hold, the implications are profound. It suggests that humans arrived in the Americas thousands of years earlier than previously believed—perhaps even during the Last Glacial Maximum, when massive ice sheets covered much of the northern hemisphere.

How did they get here? Were there earlier migration routes along the coast or through interior ice-free corridors? And why has so little evidence of these early travelers survived?

The new study doesn’t answer those questions, but it reshapes the timeline in which scientists must look for them.

“This changes the frame,” Windingstad said. “It opens the door to new hypotheses and demands that we look further back.”

From Accidental Visit to Historic Breakthrough

Holliday wasn’t even supposed to find the site. His 2012 trip to White Sands was meant for unrelated geological research. On a whim, he asked if he could visit an area on the neighboring missile range—a restricted section used by the U.S. Army.

“Next thing I know, there we were on the missile range,” he said with a chuckle.

He and a graduate student examined old trench cuts made by earlier researchers. Just 100 yards away, hidden beneath gypsum and ancient clay, the tracks lay in silence—unseen, unknown. It would take seven more years before a team from Bournemouth University and the U.S. National Park Service would unearth them, and nine years before Holliday’s earlier geological data would help verify their age.

That kind of serendipity, Holliday says, is rare in science. And it’s part of what makes this discovery so powerful.

“I really had no doubt from the outset because the dating we had was already consistent,” he said. “Now, we have direct data from the field—and a lot of it.”

The Future Beneath the Sand

For now, the ancient footprints at White Sands remain a source of wonder and debate. They may be walked over by skeptics and celebrated by believers, but they endure—pressed into the Earth by humans whose names we’ll never know, yet whose steps are guiding us toward a new understanding of our shared past.

They remind us that science is not a fixed story—it’s a journey, always rewritten by the next discovery, the next question, the next footprint left behind in the sands of time.

Reference: Vance Holliday, Paleo-lake Geochronology Supports Last Glacial Maximum (LGM) Age for Human Tracks at White Sands, New Mexico, Science Advances (2025). DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.adv4951. www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.adv4951