Symbols are powerful. They carry meanings beyond words, weaving stories of identity, authority, and belief into the fabric of culture. In the ancient Levant, one such symbol was the palmette—a stylized image of the date palm, often depicted with a central stem and radiating fronds. More than decoration, the palmette became a mirror of shifting politics, religion, and society.

In a recent study published in the Levant journal, scholar Reli Avisar traces the evolution of the palmette, showing how its meaning transformed across centuries. What began as a motif of prestige among elites gradually became a symbol of royal authority in Judah, reflecting not only local traditions but also the immense influence of the Assyrian Empire.

The Palmette of the Elite

During the Bronze and Iron Ages, the palmette was a common decorative motif throughout the Levant. It adorned personal items belonging to the wealthy and powerful—seals, ornaments, and weights. In Judah specifically, early examples from the late 9th and early 8th centuries BCE suggest its association with the local elite. These objects were not public monuments but personal belongings, intimate possessions that reinforced identity and status.

At this stage, the palmette carried meanings tied to prosperity, blessing, and perhaps divine protection. Like the date palm itself—tree of fruit, shade, and resilience—the palmette was a sign of life and continuity. Yet its presence was limited. It was a language of exclusivity, marking the boundaries of wealth and power within Judahite society.

The Shadow of Empire

Everything began to change in the latter half of the 8th century BCE. The Assyrian king Tiglath-Pileser III (not II, as sometimes confused in records) extended his empire’s might into the Levant, subduing kingdoms and transforming political landscapes. The Northern Kingdom of Israel fell, and Judah found itself under heavy Assyrian influence.

This imperial pressure reshaped not only politics but also culture. Judah adopted new bureaucratic systems, a more specialized economy, and symbols that reflected both submission and adaptation. The Assyrian kings themselves were masters of imagery, and their chosen emblem was the rosette, which decorated their clothing, crowns, and palace reliefs. The rosette projected divine favor and royal legitimacy—a visual shorthand for absolute authority.

The Palmette as a Royal Symbol

King Manasseh of Judah, ruling in the 7th century BCE, recognized the power of symbols. In a bold move, he appropriated the palmette, a motif already familiar within Judah’s elite circles, and elevated it to a royal emblem. This was a strategic act of communication. To his own people, the palmette evoked continuity with local traditions. To the Assyrian overlords, it echoed the language of empire, signaling that Judah understood and respected imperial codes of power.

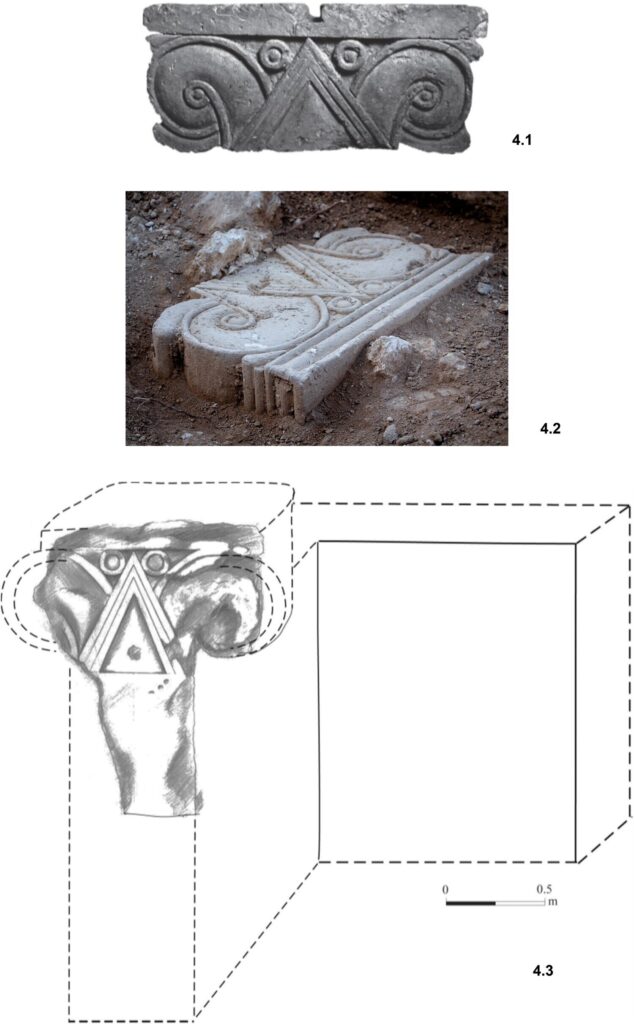

Thus, the palmette crossed a threshold: no longer a private emblem of the elite, it became public, monumental, and royal. It appeared on stone volute capitals—architectural features crowning columns—and on luxury ivory carvings linked to Jerusalem’s royal court.

One striking example comes from the ivory plaques discovered in the Giv‘ati Parking Lot excavation in Jerusalem. These plaques, associated with Building 100 near the royal court, carried designs that married local and imperial imagery. A central palmette was framed by twelve rosettes, a direct echo of Assyrian royal motifs. This blending of symbols illustrates how Judah’s rulers sought legitimacy through visual synthesis—honoring tradition while aligning with imperial authority.

Echoes of Assyrian Grandeur

The palmette designs from Judah were not isolated creations but part of a broader cultural dialogue. Similar motifs appear in Assyrian palaces of the 8th and 7th centuries BCE, carved into stone thresholds, pavements, and monumental art. Judahite artisans likely drew direct inspiration from these works, adapting imperial aesthetics to local contexts.

What emerges is a story of negotiation. Symbols became tools of diplomacy and survival. By reshaping the palmette into a royal emblem framed by Assyrian imagery, Judah’s kings embedded themselves in a wider network of power while maintaining ties to their own cultural roots.

Decline and Disappearance

But symbols are not eternal. Their meanings shift with time, and sometimes they are deliberately discarded. After King Josiah’s reforms in the late 7th century BCE, the palmette seems to have lost its royal connotations. Josiah’s religious and political agenda sought to centralize worship and distance Judah from foreign influences. In this new vision, the palmette, once elevated by Manasseh, no longer served as a useful emblem.

The most telling evidence comes from Armon HaNatziv, where volute capitals adorned with palmettes were intentionally buried. Strikingly, two capitals were carefully placed one above the other, blocking a rock-hewn niche. Unlike other stone blocks, which were often recycled for new construction, these capitals were preserved in place. Their deliberate burial suggests a conscious rejection of the symbol—an act of silencing its royal voice.

This treatment contrasts with typical patterns of reuse and destruction. Here, the act of burial itself becomes symbolic, a physical expression of changing ideologies. What once conveyed authority was now set aside, protected yet stripped of meaning.

The Palmette’s Legacy

Reli Avisar’s research offers more than a catalog of motifs. It shows how art and symbolism intersect with politics, how the visual language of power evolves alongside empires and kingdoms. The palmette’s journey—from elite ornament, to royal emblem, to discarded relic—mirrors the shifting tides of Judah’s history.

Unlike earlier studies that focused on stylistic variations, this work illuminates the social and political transformations embedded within a single symbol. The palmette is not just decoration; it is a witness to centuries of negotiation between identity and authority, tradition and empire.

The Human Story Behind the Symbol

What makes this story emotionally resonant is the recognition that symbols are never static. They are alive, reshaped by the people who use them, infused with meanings that speak to specific times and places. The palmette reminds us that human societies continually reinvent their language of power, balancing the pull of tradition with the demands of survival.

For the Judahite elite, the palmette was a mark of prestige. For Manasseh, it was a royal standard. For Josiah, it was a relic to be buried. Today, for us, it is a key to unlocking the layered history of the ancient Levant.

The palmette’s story is not just about an image carved in stone or ivory—it is about how humans use symbols to define who they are, to claim authority, and to negotiate their place in a changing world. Through its fronds and stem, we glimpse the rise and fall of kingdoms, the shadows of empire, and the resilience of cultural identity.

More information: Reli Avisar, Rooted in power: the transformation of the palmette motif from an elite symbol to a marker of royal authority in Iron Age Judah, Levant (2025). DOI: 10.1080/00758914.2025.2536979