On England’s south coast, in two quiet 7th-century cemeteries, archaeologists have uncovered an unexpected chapter in the island’s history. The DNA of two individuals, buried more than 1,300 years ago, shows that each had a grandparent from West Africa — a striking reminder that migration and cultural exchange reached far beyond what most people imagine for the Early Middle Ages.

The findings, published in the journal Antiquity, challenge the idea that migration into early medieval England came only from nearby parts of Europe. They paint a picture of a surprisingly connected world, where people, ideas, and goods traveled across continents long before the age of sail.

England’s Early Medieval Crossroads

The Early Middle Ages in England were a time of profound change. Historical sources describe the arrival of the Angles, Saxons, and Jutes from continental northern Europe, whose influence shaped the language, culture, and political landscape of what became the Anglo-Saxon period. Archaeologists have long debated how far other, more distant migrations reached — and whether those journeys left any lasting mark on the population.

“Migration and its direction, scale, and impact have been much debated in European archaeology,” note the study’s authors. “Archaeogenetic research can now provide new insight, even identifying individual migrants.”

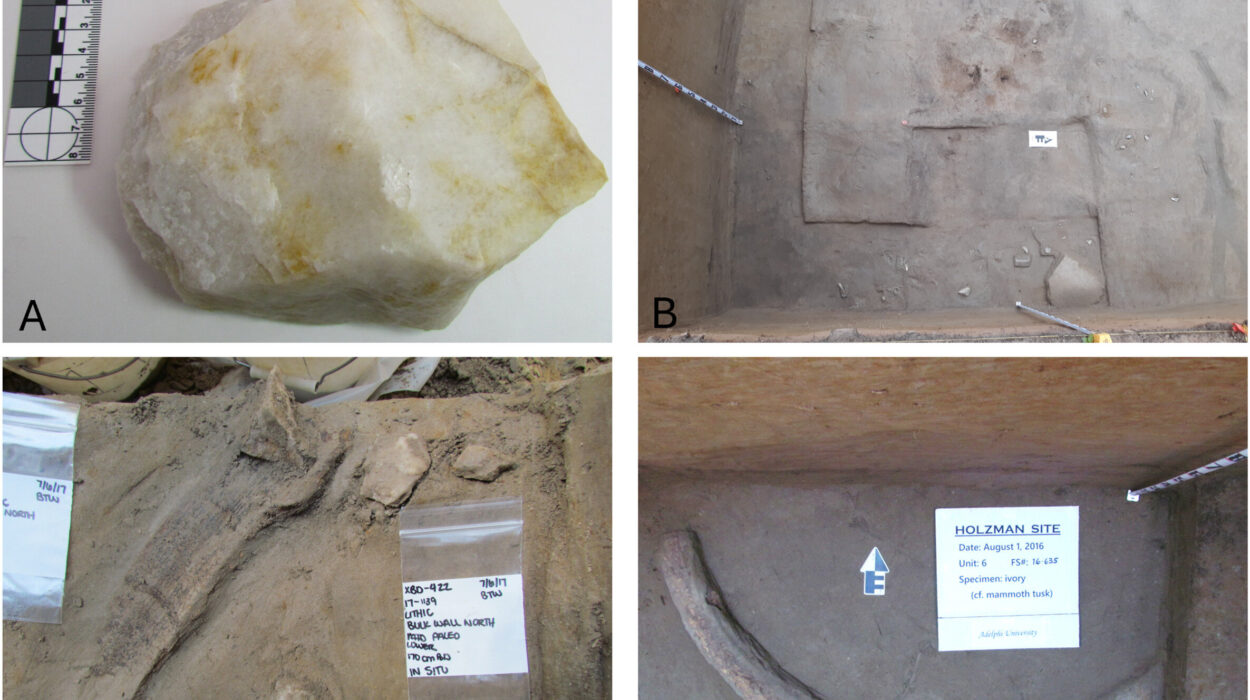

To investigate, researchers analyzed ancient DNA from skeletal remains at two cemeteries: Updown in Kent and Worth Matravers in Dorset. The two sites, though separated by geography and culture, both belonged to communities that were part of early medieval England’s complex social network.

The Unexpected Genetic Story

Most individuals buried in these cemeteries had ancestry typical for the time — a mix of northern European and western British or Irish heritage. But one burial at each site stood out.

At both Updown and Worth Matravers, researchers found an individual whose genetic profile revealed recent West African ancestry. Their mitochondrial DNA — inherited only from the mother — was northern European, but their autosomal DNA, which comes from both parents, showed unmistakable affinities with present-day Yoruba, Mende, Mandenka, and Esan populations of sub-Saharan West Africa.

Careful analysis suggests that in both cases, the individuals’ West African ancestor was likely a paternal grandparent. This wasn’t distant genetic noise; it was a relatively recent connection.

Kent’s Royal Network and an International Life

Updown, in Kent, was no ordinary settlement. Situated close to the royal center of Finglesham, it was deeply connected to continental Europe. Professor Duncan Sayer of the University of Central Lancashire, lead author of the Updown study, describes the area’s “Frankish Phase” in the 6th century — a time of intense contact with the nearby Frankish kingdoms.

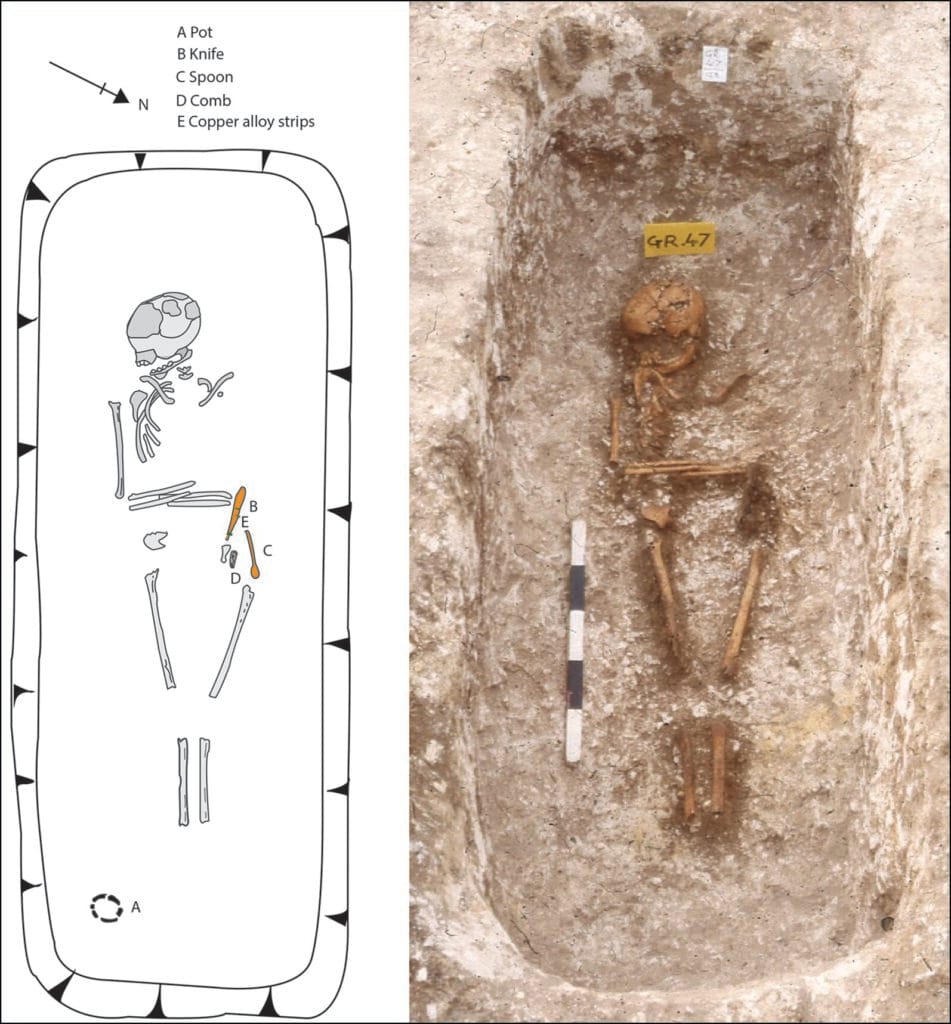

The man with West African ancestry buried at Updown was laid to rest with goods that spoke of far-reaching connections: a pot possibly imported from Frankish Gaul, and a spoon that may have symbolized Christian faith or even links to the Byzantine Empire. These objects, paired with his genetic heritage, hint at a life embedded in a network that spanned continents.

Dorset’s Coastal Outlier

Worth Matravers, on the other hand, lay on the western fringe of Anglo-Saxon cultural influence. Dr. Ceiridwen J. Edwards of the University of Huddersfield, lead author of the Worth Matravers study, notes that Dorset had a “marked and notable cultural divide” from areas under strong Anglo-Saxon influence.

Here, the individual with West African ancestry was buried alongside a man of British heritage and an anchor carved from local limestone — a symbol perhaps tied to seafaring or faith. While the setting was culturally distinct from Kent, the genetic evidence shows that even in this peripheral area, global connections reached deep into the community.

Fully Part of Their Communities

Perhaps most striking is that in both cases, these individuals were buried in exactly the same manner as their neighbors. Their graves showed no sign of being treated as outsiders; instead, they were integrated members of their societies. This suggests that, despite their unusual heritage, they were respected and valued in life and honored in death.

“It is significant that it is human DNA — and therefore the movement of people, not just objects — that is now starting to reveal the nature of long-distance interaction to the continent, Byzantium, and sub-Saharan Africa,” says Professor Sayer.

Rethinking the Early Medieval World

The findings have profound implications for our understanding of migration in the Early Middle Ages. They show that the people of early medieval England lived in a world far more interconnected than previously thought. These were not isolated farming communities; they were part of a network that could stretch across seas, continents, and cultures.

“What is fascinating about these two individuals,” says Sayer, “is that this international connection is found in both the east and west of Britain.”

Dr. Edwards adds: “Our joint results emphasize the cosmopolitan nature of England in the early medieval period, pointing to a diverse population with far-flung connections who were, nonetheless, fully integrated into the fabric of daily life.”

A New Chapter in the Story of the Past

The discoveries at Updown and Worth Matravers are more than genetic curiosities — they are reminders that the past was never static. People have always moved, mingled, and reshaped communities in ways both visible and invisible.

As archaeologists continue to unlock the secrets of ancient DNA, more of these personal stories will emerge, bridging the gap between the silent bones beneath our feet and the vibrant, interconnected world they once inhabited.

More information: Duncan Sayer et al, West African ancestry in seventh-century England: two individuals from Kent and Dorset, Antiquity (2025). doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2025.10139

M. George B. Foody et al, Ancient genomes reveal cosmopolitan ancestry and maternal kinship patterns at post-Roman Worth Matravers, Dorset, Antiquity (2025). doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2025.10133