In a quiet corner of Belgium, tucked within a lush nature reserve along the banks of the Hoyoux River, a team of archaeologists is unearthing secrets that lay buried for tens of thousands of years. The cave of Trou Al’Wesse, nestled beneath a limestone outcrop in the municipality of Modave, has become the focus of an ambitious new excavation campaign led by the University of Liège. And what they are discovering is nothing short of extraordinary: evidence of some of the earliest Homo sapiens to ever settle in northwestern Europe.

The story of this site begins in the mists of the Paleolithic—around 40,000 years ago—when our modern human ancestors arrived in Europe and began to shape the cultural, technological, and artistic foundations of the Upper Paleolithic period. The sediment layers at Trou Al’Wesse are a time capsule of that pivotal moment, preserving traces of life in a changing world where humans, mammoths, and reindeer once roamed the same landscapes.

Reviving a Forgotten Cave with Cutting-Edge Science

Though the site was first explored in the 1830s by pioneering paleontologist Philippe-Charles Schmerling and later by Edouard Dupont in the 1860s, their efforts, while groundbreaking for their time, lacked the scientific precision modern archaeology demands. The tools and bones they unearthed were extracted without clear stratigraphic data—the kind of layer-by-layer context that allows today’s scientists to reconstruct life in the distant past with accuracy.

“Much of the material collected during those early excavations has unfortunately been lost,” explains Damien Flas, an archaeologist at the University of Liège. “But that doesn’t mean the story was over.”

In the late 1980s, the University of Liège returned to the site with renewed determination. It took nearly two more decades, until 2003, for deeper surveys to reveal untouched sedimentary layers just outside the disturbed interior of the cave. These layers—still pristine after 40 millennia—contained tools, ornaments, and other cultural traces left by the first anatomically modern humans to permanently inhabit the region.

Echoes of the Aurignacians: Art, Tools, and Symbolism

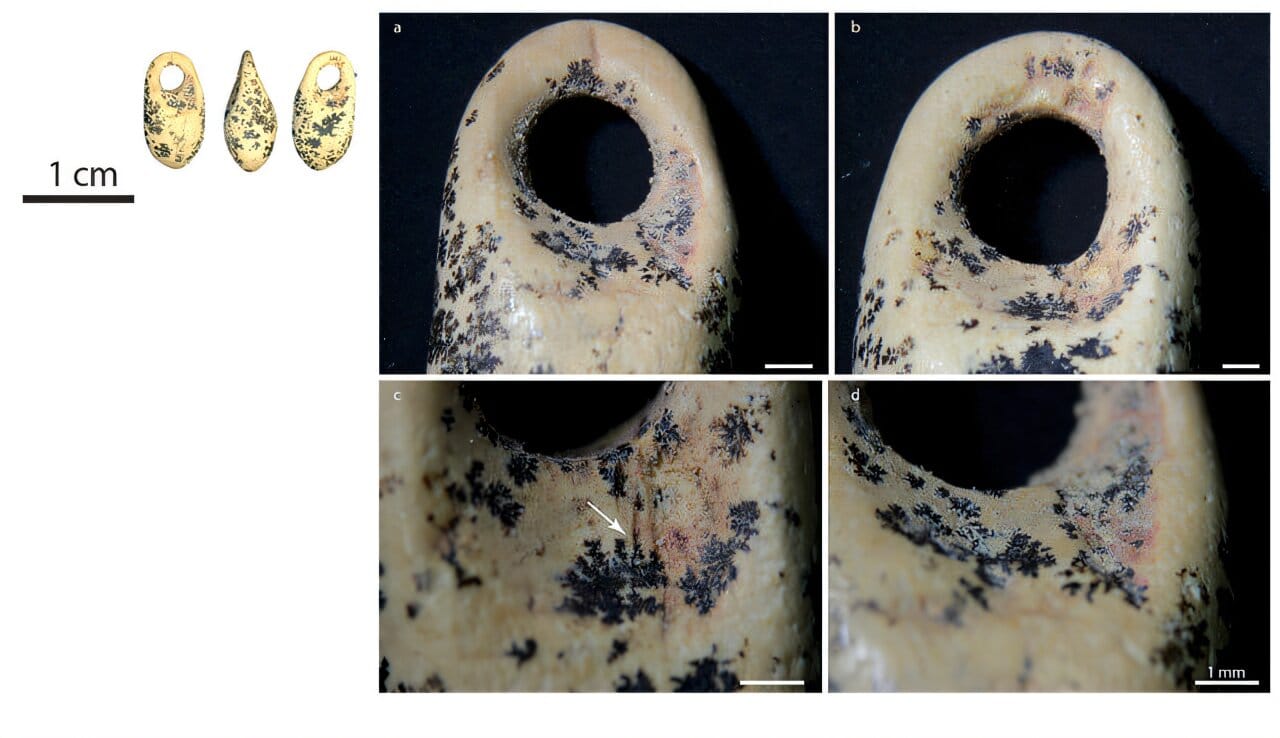

Among the most compelling discoveries are finely crafted flint tools, spearheads carved from reindeer antler, and objects made from mammoth ivory—including decorative beads and fragments bearing engravings. Radiocarbon dating has confirmed that many of these items are over 35,000 years old, placing them firmly in the Aurignacian period.

The Aurignacian culture is considered one of the earliest expressions of symbolic and artistic behavior in Europe. Emerging shortly after Homo sapiens arrived on the continent, this cultural complex is linked to the first known examples of cave art—like the haunting animal murals of Chauvet Cave in France—and to the production of carved figurines, musical instruments, and personal ornaments.

“These discoveries at Trou Al’Wesse contribute to our understanding of this key moment in human history,” says Veerle Rots, an archaeologist at ULiège and director of the TraceoLab, which specializes in experimental archaeology and use-wear analysis. “They show us how early Homo sapiens adapted, innovated, and expressed themselves creatively in a new and challenging environment.”

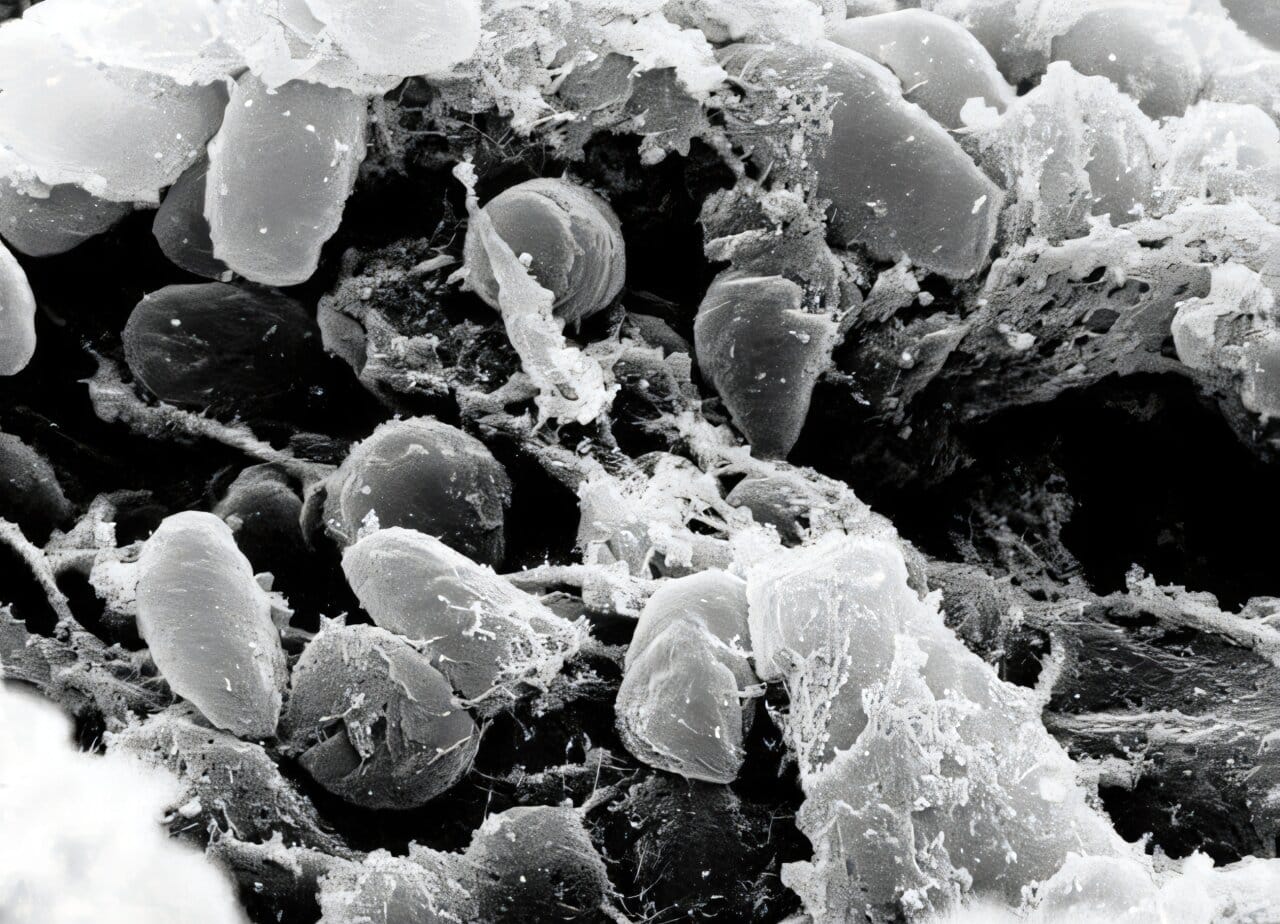

By examining wear patterns on the tools, residue traces, and the microstructure of the ivory and antler objects, the researchers hope to reconstruct not just what these early people made—but how they lived, what they hunted, and how they interacted with their environment.

A Living Laboratory for the Next Generation of Scientists

The work being done at Trou Al’Wesse is not only illuminating the deep past—it’s also shaping the future. Every summer, the site becomes a vibrant outdoor classroom where archaeology students from Belgium and across Europe—Brussels, Toulouse, Bordeaux—receive hands-on training in excavation techniques, stratigraphy, and artifact analysis.

“It’s an exceptional learning opportunity,” says Flas. “Students don’t just read about prehistoric lifeways in a textbook. They get to hold those lives in their hands, quite literally. They learn how to ask the right questions, how to observe, and how to think like archaeologists.”

The experience fosters not just academic skills, but a sense of stewardship and wonder. For many students, this work becomes a calling—an invitation to take part in the grand narrative of human history, where each artifact is a voice from the past, waiting to be heard.

Belgium’s Hidden Paleolithic Heritage

Though overshadowed at times by more famous sites in France and Germany, Belgium is home to an extraordinary array of Paleolithic sites. Alongside Trou Al’Wesse are the remarkable caves of Spy and Goyet, which have yielded important Neanderthal and early modern human remains. These sites form a rich regional archive of human evolution, migration, and cultural development.

What sets Trou Al’Wesse apart is its unique preservation and the clarity of its stratigraphy. In a region that has been repeatedly shaped by glaciation, erosion, and modern activity, finding intact layers from 35,000 to 40,000 years ago is extremely rare. It offers a direct line to a time when Homo sapiens were newcomers in Europe—struggling to survive, adapt, and perhaps leave behind the first traces of symbolic thought.

“This is not just a Belgian story,” says Rots. “It’s a European story. A human story. We are piecing together one of the most important chapters in the history of our species.”

The Future of the Past

The current excavation campaign is supported by a network of institutions, including the University of Bordeaux, and is part of a broader effort to integrate new technologies into archaeological research. Ground-penetrating radar, 3D modeling, and high-resolution geochemical analysis are allowing the team to uncover subtle patterns that would have been invisible just a decade ago.

They are also exploring the potential for ancient DNA analysis—not of human remains, which have not yet been found at the site, but of sediment DNA, which can capture genetic traces left behind by humans and animals in soil layers. This technique, known as environmental DNA (eDNA), could one day help reconstruct the species composition of the ecosystem at the time Homo sapiens lived there.

Each summer adds a new layer of understanding. And as the site continues to yield secrets, the story of Trou Al’Wesse becomes richer—not just in data, but in meaning.

Why This Matters

At first glance, a cave in a remote Belgian forest might not seem like a place that changes the way we think about humanity. But Trou Al’Wesse does just that. It reminds us that our species has always been a migrant, a maker, a dreamer. That even in the cold and peril of the Ice Age, humans carved beauty into ivory, made tools with precision, and sought to express something beyond mere survival.

It also teaches us the fragility of memory. Had the site been left untouched—or worse, destroyed—we might have lost this chapter forever. Archaeology is, at its heart, an act of rescue: a race against time, erosion, and neglect to preserve the traces of lives long past.

In doing so, it doesn’t just fill museum cases or academic journals. It enriches us. It connects us to those who came before, and perhaps helps us better understand who we are today.

A Portal to the Beginning of Us

Trou Al’Wesse is not just a dig site. It is a portal to the beginning of us—not just Homo sapiens, but modern humans as we understand them: symbolic, social, inventive, and artistic. With each flake of flint, each sliver of ivory, the veil of prehistory lifts just a little more.

As students crouch over excavation grids with trowels in hand, as scientists analyze the fine grooves on a mammoth ivory bead, they are not just studying the past. They are standing at the threshold of the human journey—40,000 years long and still unfolding.

And beneath that limestone bluff in Modave, the voices of the first Europeans whisper through the soil: we were here, and we mattered.