In a quiet corner of northern Spain, deep within the fossil-rich Sierra de Atapuerca, scientists have unearthed a discovery that challenges our understanding of Ice Age Europe. At first glance, it may seem unremarkable—a single fossilized tooth. But this ancient molar, recovered from the Galería site near Burgos, tells a story of survival, migration, and climate extremes dating back nearly 300,000 years.

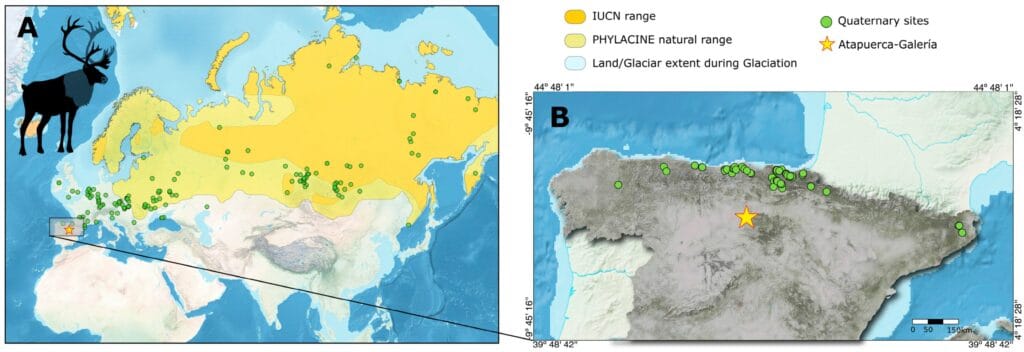

The tooth belonged to a reindeer (Rangifer), a cold-adapted species we typically associate with the icy tundras of northern Europe, Siberia, or modern-day Scandinavia. Yet here it was, fossilized beneath the Iberian soil, far to the south of its expected range. According to a new study published in the journal Quaternary, this lone tooth is the earliest known record of glacial fauna ever found in the Iberian Peninsula.

It’s not just a story of one animal in the wrong place—it’s a revelation that reshapes the Ice Age landscape of southern Europe.

Reindeer Beneath the Pines: A Glimpse into a Glacial Iberia

The Galería fossil was uncovered from a stratigraphic layer known as GIIIa, which dates to between 243,000 and 300,000 years ago during the Middle Pleistocene. That same layer has previously yielded stone tools and a human cranial fragment, offering a rare and intimate snapshot of life at a time when the climate was far more volatile than it is today.

The presence of reindeer in this context is striking. Reindeer are adapted to cold, open environments, like the steppe-tundra ecosystems that blanketed much of Eurasia during glacial periods. Their teeth and bones are rarely found this far south, especially in pre-Last Glacial Maximum layers. This makes the Galería discovery one of the southernmost reindeer remains ever found in Eurasia.

“This fossil helps to refine the dating of the site’s stratigraphic levels,” explains Jan van der Made, a paleontologist at the Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales (MNCN-CSIC) and co-author of the study. “But more importantly, it provides evidence of the intensity of glacial periods that affected the peninsula’s inhabitants during the Pleistocene.”

In other words, this tiny tooth reveals a moment when the Iberian Peninsula, now known for its sunny Mediterranean climate, was gripped by icy winds and tundra-like conditions.

Humanity’s Cold Neighbors: Coexistence in the Middle Pleistocene

Perhaps most fascinating is the fact that this reindeer lived side by side with early humans. The Galería site is part of the larger Atapuerca complex, a UNESCO World Heritage Site and one of the world’s richest records of ancient human activity. From Homo heidelbergensis to Neanderthals and beyond, this region has preserved the physical and cultural traces of our deep ancestors.

The discovery of the reindeer tooth in the same sedimentary layer as stone tools and human bone confirms a shared ecosystem—a rare and invaluable convergence in the fossil record. It raises important questions about how early humans adapted to such harsh conditions.

“This work highlights the importance of studying the biogeographic patterns of glacial fauna,” says Ignacio Aguilar Lazagabaster, a researcher at the Centro Nacional de Investigación sobre la Evolución Humana (CENIEH). “It allows us to better understand the adaptive capacity of human populations during the Middle Pleistocene.”

In other words, by tracking the movement of animals like reindeer, we can infer much about the environments humans lived in, the strategies they used to survive, and the timing of their migrations across the continent.

A Southern Refuge in a Northern World

Traditionally, southern Europe—especially the Iberian, Italian, and Balkan peninsulas—has been viewed as a refuge for temperate species during the Ice Age. When glaciers advanced, many plants and animals retreated southward to escape the cold. After the glaciers receded, they recolonized northern latitudes.

This view, while still broadly accurate, now requires refinement. The Galería reindeer suggests that glacial fauna were able to penetrate deep into the south—not just in the final glacial periods, but much earlier than previously believed.

According to van der Made, the presence of such species “indicates that extreme cold may have impacted Iberian fauna earlier and more severely than previously thought.” The region may not have been as insulated from the harshness of the Pleistocene as once imagined.

This supports other recent findings suggesting that even the heart of Spain experienced tundra-like environments during glacial maxima, home to now-extinct megafauna such as mammoths, woolly rhinoceroses, and, yes, reindeer. Some of these creatures ranged as far south as Madrid and Granada—well below the latitude of Atapuerca.

What One Tooth Can Teach Us

Fossils like this tooth are more than remnants of the past. They are data points in the vast, unfinished puzzle of Earth’s history. Every layer of sediment tells a story, every bone a lesson in climate, ecology, and adaptation. And when these stories intersect—when a reindeer’s journey meets a human’s hammerstone—we learn not just about animals or geology, but about ourselves.

The Galería tooth is a subtle reminder that the boundaries we assume—between warm and cold, north and south, ancient and modern—are often blurrier than we think. Nature doesn’t follow human rules. Species migrate, adapt, or vanish based on forces we’re still trying to understand. And human beings, ever resilient, have lived through it all.

This discovery underscores the value of sites like Atapuerca, where the past is written in stone and bone, waiting patiently for those who know how to read it.

A Glacial World Reimagined

As climate change reshapes our modern environment, discoveries like this reindeer tooth remind us that Earth’s climate has never been static. But they also highlight the resilience—and fragility—of ecosystems and the species that inhabit them.

The Iberian Peninsula once hosted reindeer beneath its pines and mammoths on its plains. Early humans survived and thrived here under conditions more extreme than many scientists previously assumed. Understanding how they did so—through migration, innovation, and adaptation—may offer clues for how we too can navigate a world in flux.

For now, this fossilized tooth—silent for 300,000 years—speaks volumes. It is not just a relic, but a revelation. A single point in time that redefines the edge of an Ice Age world, and reconnects us to the deep, shared story of life on Earth.

More information: Jan van der Made et al, Southernmost Eurasian Record of Reindeer (Rangifer) in MIS 8 at Galería (Atapuerca, Spain): Evidence of Progressive Southern Expansion of Glacial Fauna Across Climatic Cycles, Quaternary (2025). DOI: 10.3390/quat8030043 www.mdpi.com/2571-550X/8/3/43