Imagine holding a mammoth tooth in your hand—a relic of a creature that walked the Earth over a million years ago. The bone feels cold, fossilized, silent. Yet within its microscopic cracks lies a story far more astonishing than the weight of the fossil itself. Hidden in the ancient remains of woolly and steppe mammoths, scientists have uncovered microbial DNA preserved for over one million years—making it some of the oldest microbial genetic material ever recovered.

This groundbreaking discovery, led by an international team at the Center for Paleogenetics in Stockholm, Sweden, is more than just a scientific achievement. It is a time capsule into the invisible world that once lived alongside these giant Ice Age creatures. Not only did the mammoths roam the frozen tundra, but within them thrived entire microbial communities—some friendly, others potentially deadly. For the first time, we are beginning to glimpse how these microscopic partners may have shaped the lives, health, and perhaps even the fate of the mammoths.

Unlocking DNA Older Than Time’s Silence

The research team analyzed microbial DNA from 483 mammoth specimens, of which 440 had never been sequenced before. Among them was the genetic material from a steppe mammoth that lived approximately 1.1 million years ago. Using cutting-edge genomic sequencing and bioinformatics, the scientists were able to distinguish microbes that once lived inside the mammoths from those that infiltrated their remains long after death.

“Imagine holding a million-year-old mammoth tooth. What if I told you it still carries traces of the ancient microbes that lived together with this mammoth?” says Benjamin Guinet, postdoctoral fellow at the Center for Paleogenetics and lead author of the study. “Our results push the study of microbial DNA back beyond a million years, opening up new possibilities to explore how host-associated microbes evolved in parallel with their hosts.”

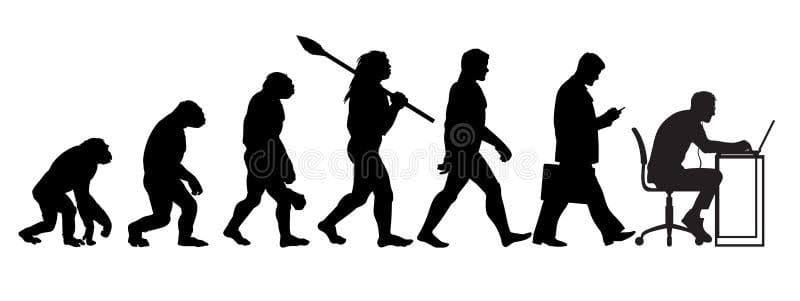

For decades, scientists have managed to extract DNA from ancient animals, tracing evolutionary history through their genes. But this is different. Instead of just the mammoths themselves, researchers are now beginning to reconstruct the microbial ecosystems that coexisted within these creatures—an entirely new dimension of paleogenetics.

Microbial Companions Across Time

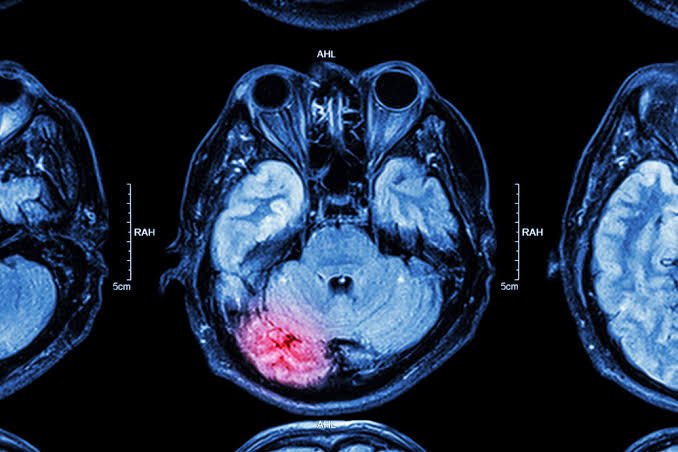

Among the preserved DNA were traces of six microbial groups consistently associated with mammoths. These included ancient relatives of Actinobacillus, Pasteurella, Streptococcus, and Erysipelothrix—microbes that are still found in living animals today. Some may have lived harmlessly within the mammoth’s body, while others could have posed serious health risks.

One striking discovery was a Pasteurella-related bacterium, closely related to a modern pathogen that causes fatal outbreaks in African elephants. Given that African and Asian elephants are the closest living relatives of mammoths, this raises fascinating—and unsettling—questions. Did mammoths suffer similar epidemics? Could microbial disease have contributed, at least in part, to their vulnerability and eventual extinction?

Even more remarkable, the researchers managed to reconstruct partial genomes of Erysipelothrix from a 1.1-million-year-old steppe mammoth. This represents the oldest host-associated microbial DNA ever recovered, pushing the limits of what science thought possible.

“As microbes evolve fast, obtaining reliable DNA data across more than a million years was like following a trail that kept rewriting itself,” explains Tom van der Valk, senior author of the study. “Our findings show that ancient remains can preserve biological insights far beyond the host genome, offering us perspectives on how microbes influenced adaptation, disease, and extinction in Pleistocene ecosystems.”

Disease, Coexistence, and Evolution

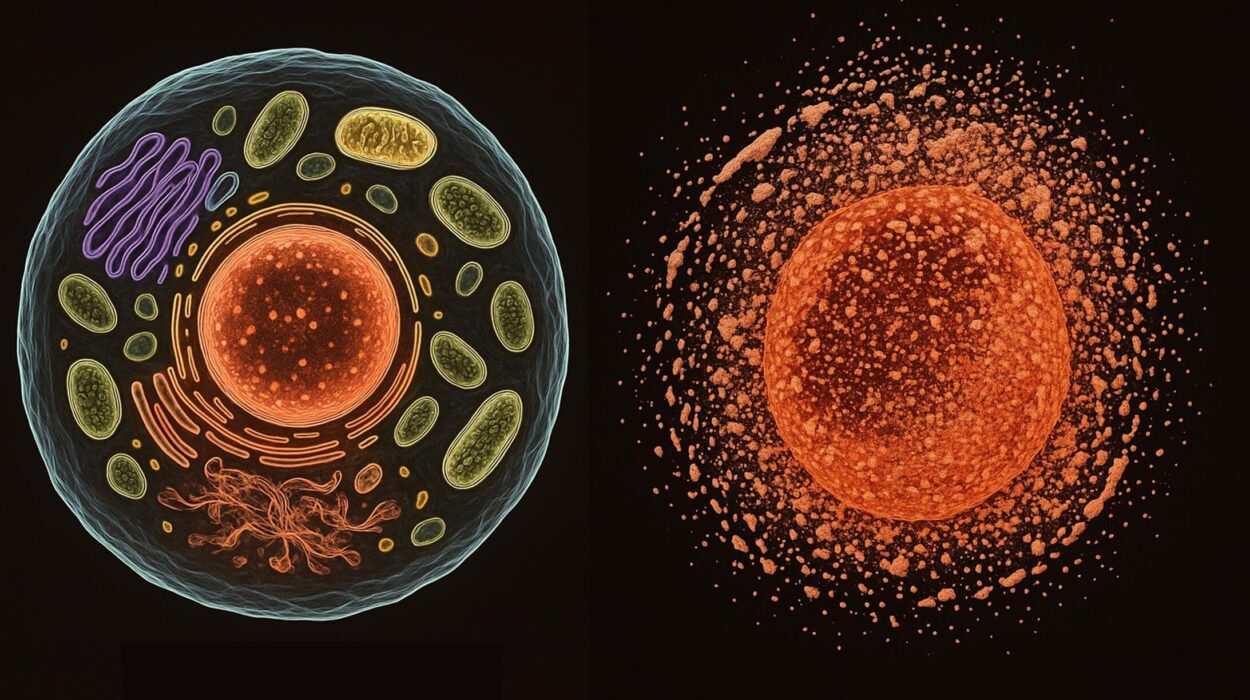

The relationship between animals and their microbes is complex—sometimes beneficial, sometimes dangerous. Microbes help digest food, train the immune system, and protect against harmful invaders. But they can also spark disease and death. By revealing which microbial lineages were present in mammoths, the study highlights a dynamic history of coexistence, conflict, and coevolution.

What stands out is the persistence of certain microbial groups over enormous timescales. Some lineages appear to have lived within mammoths for hundreds of thousands of years, stretching from their early ancestors more than a million years ago to the woolly mammoths that survived on Wrangel Island just 4,000 years ago. This suggests that the microbial communities of mammoths were not random; they were long-term partners in survival, shaping and being shaped by their giant hosts.

A New Window Into Lost Ecosystems

While the precise effects of these microbes on mammoth health remain uncertain, the findings open an entirely new field of research. Traditionally, paleogenetics has focused on the DNA of extinct animals themselves. But now, scientists can look beyond the hosts to study the microbiomes of the past—the invisible ecosystems that influenced their lives.

“This work opens a new chapter in understanding the biology of extinct species,” says Love Dalén, Professor of Evolutionary Genomics at the Center for Paleogenetics. “Not only can we study the genomes of mammoths themselves, but we can now begin to explore the microbial communities that lived inside them.”

In other words, mammoth fossils no longer tell us just about bones and tusks. They whisper stories about diseases endured, symbiotic partnerships sustained, and microbial battles fought inside ancient bodies. They allow us to reconstruct the intimate biology of extinction.

Why This Discovery Matters Today

At first glance, studying ancient mammoth microbes may seem like a curiosity from the frozen past. But the implications stretch into the present and future. Understanding how pathogens coexisted with extinct species may shed light on modern elephant health and conservation. It may also deepen our grasp of how microbes shape ecosystems, adapt to hosts, and sometimes drive species toward collapse.

In a world where emerging diseases frequently threaten humans and animals alike, the ability to peer back into deep time and see the microbial forces at play in extinction events is invaluable. It reminds us that life is never just about the big creatures we see—it is also about the microscopic companions we carry with us.

The Living Legacy of Mammoths

The discovery of million-year-old microbial DNA is not just a triumph of science—it is a reminder of connection. The microbes inside us today are part of a lineage stretching back through time, just as the mammoth’s microbes once shaped its destiny. We are not solitary beings; we are ecosystems, symphonies of species coexisting, competing, and surviving together.

The mammoths may be gone, their great herds silenced on the tundra, but in their teeth and bones, in fragments of DNA preserved against the odds, they still speak. They tell us that life is never lived alone—that even giants carried tiny companions on their long journey through time.

And now, more than a million years later, those companions are finally telling their stories.

More information: Ancient Host-Associated Microbes obtained from Mammoth Remains, Cell (2025). DOI: 10.1016/j.cell.2025.08.003. www.cell.com/cell/fulltext/S0092-8674(25)00917-1