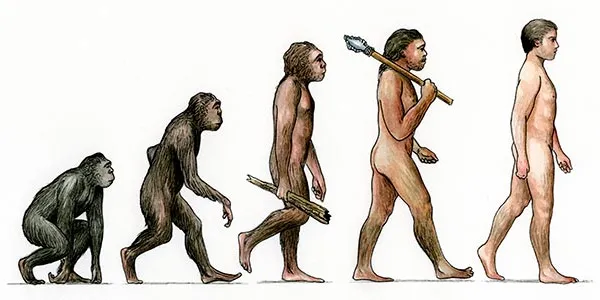

When archaeologists dig into the earth, they are not only uncovering the remains of human civilizations but also the silent witnesses that lived alongside us—animals. Recently, a groundbreaking study from the University of Montpellier in southern France revealed an extraordinary story written in bones: over the past 8,000 years, wild animals have steadily shrunk, while domestic animals have grown larger.

This finding, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, doesn’t just add a curious detail to our knowledge of history. It reshapes the way we understand the deep, intertwined relationship between humans and the creatures around us. It shows how our choices—whether deliberate or accidental—have sculpted the very bodies of animals, leaving a mark that is still visible today.

How Scientists Unlocked the Past

The study was ambitious in scope. Researchers analyzed more than 225,000 animal bones collected from 311 archaeological sites across Mediterranean France. These bones belonged to both wild animals—like foxes, rabbits, and deer—and domestic species, such as cattle, pigs, goats, sheep, and chickens.

The scientists weren’t just looking at bones as relics; they treated them as biological records. Every length, width, and curve told a story about body size, health, and the conditions animals lived in. To deepen their understanding, they paired these measurements with other historical data: ancient climate patterns, vegetation changes, population growth, and land use.

By applying sophisticated statistical modeling, they pieced together an evolutionary timeline—one that showed not only how animal size changed over millennia, but also why it changed.

Parallel Paths: Animals and Humans in Sync

For thousands of years, wild and domestic animals followed similar trajectories. Their body sizes rose and fell in unison, shaped by a mix of climate and human influence. For example, during harsher climates or periods of agricultural expansion, both wild deer and domestic goats might shrink, reflecting the scarcity of food and tougher living conditions.

This synchrony tells us something profound: for much of history, humans and animals existed in a shared ecological rhythm. The forces of nature—climate shifts, plant growth, seasonal abundance—were as powerful for the fox and rabbit as they were for the goat and sheep.

A Turning Point in the Middle Ages

But then, around 1,000 years ago, everything changed. The study revealed a striking divergence in animal evolution. Domestic animals began to grow larger, while wild animals shrank dramatically. This split was no coincidence—it was the result of human intervention becoming the dominant evolutionary force.

In the Middle Ages, agricultural societies began to breed animals more deliberately. Cows were selected for greater milk production, pigs for more meat, and chickens for larger eggs. Over generations, selective breeding amplified these traits, producing bigger, stronger, and more productive livestock.

At the same time, wild animals faced increasing pressure. Expanding human populations cut down forests for farmland, reducing habitats. Hunting intensified, targeting the largest and healthiest animals, which left smaller individuals to reproduce. Over centuries, these combined pressures nudged wild populations toward smaller body sizes.

Human Hands on the Scale of Evolution

The study’s authors put it bluntly: natural selection shaped animals for thousands of years, but in the last millennium, human influence took over. Evolution didn’t stop, but it began to follow our rules.

Domestic animals grew because we wanted them to. Wild animals shrank because we constrained them. The bones tell a story of divergence—one species flourishing under human control, the other adapting under human pressure.

This discovery isn’t just about size. Body size is what scientists call a “sensitive indicator,” meaning it reflects broader systemic change. Larger livestock meant a shift in agricultural economies, diets, and human survival. Smaller wild animals signaled ecosystems under strain, resilience under threat, and a world bending under human expansion.

Lessons for the Present

Although this research looks deep into the past, its message speaks urgently to the present. Today, human influence on the natural world is stronger than ever. We’ve accelerated habitat loss, overfishing, and climate change to the point where many species are shrinking again—not just in size, but in population.

The Montpellier study reminds us that what we do today echoes for millennia. When humans began selectively breeding livestock or clearing land in medieval France, they could not have imagined that their choices would be measurable a thousand years later. Yet here we are, reading their story in the bones of animals.

This knowledge isn’t only a warning—it is also a guide. By understanding how animals responded to human pressures in the past, conservationists can better predict and manage the challenges facing wildlife today. It emphasizes that every decision—from how we farm to how we protect habitats—leaves an evolutionary footprint.

A Shared Evolutionary Journey

The story of shrinking wild animals and growing domestic ones is ultimately a story of interconnectedness. Humans do not exist apart from nature; we exist within it, shaping and being shaped by it. Our ancestors may not have realized that breeding bigger cows would alter the evolutionary destiny of deer, but we now know the truth: evolution does not happen in isolation.

When we look at a cow in a pasture or a rabbit darting into the undergrowth, we are not just seeing animals. We are seeing participants in a shared journey—one that we have influenced for thousands of years, and one that will continue to reflect our choices for thousands more.

The Story Written in Bones

Bones may seem lifeless, but they are storytellers of the deepest kind. In their quiet durability, they carry the memory of entire ecosystems, of the rise of civilizations, of choices both intentional and unintentional. The University of Montpellier study has given voice to those bones, revealing how profoundly we have reshaped the animal kingdom.

And perhaps the most powerful lesson is this: if we have been able to change animals so dramatically without even realizing it, then imagine what we could do if we intentionally chose to shape a future of coexistence, resilience, and respect.

More information: Mureau, Cyprien et al, 8,000 years of wild and domestic animal body size data reveal long-term synchrony and recent divergence due to intensified human impact, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (2025). DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2503428122. www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.2503428122