The Amazon rainforest is often called the “lungs of the Earth,” but in truth, it is much more than that. It is a vast green heart that pumps life into the atmosphere, circulating water, storing carbon, and stabilizing global climate systems. Its trees breathe moisture into the sky, feeding invisible rivers of vapor that flow across South America, nourishing farmlands and replenishing reservoirs thousands of kilometers away.

But this living system is under extraordinary pressure. A groundbreaking study led by researchers from the University of São Paulo (USP) has, for the first time, separated the local effects of deforestation from the broader consequences of global climate change. Their findings, published in Nature Communications and soon to be featured on its cover, reveal in stark detail how vegetation loss is reshaping the Amazon’s climate.

The message is clear: deforestation is not only destroying biodiversity—it is actively rewriting the climate of the region itself.

Quantifying the Damage

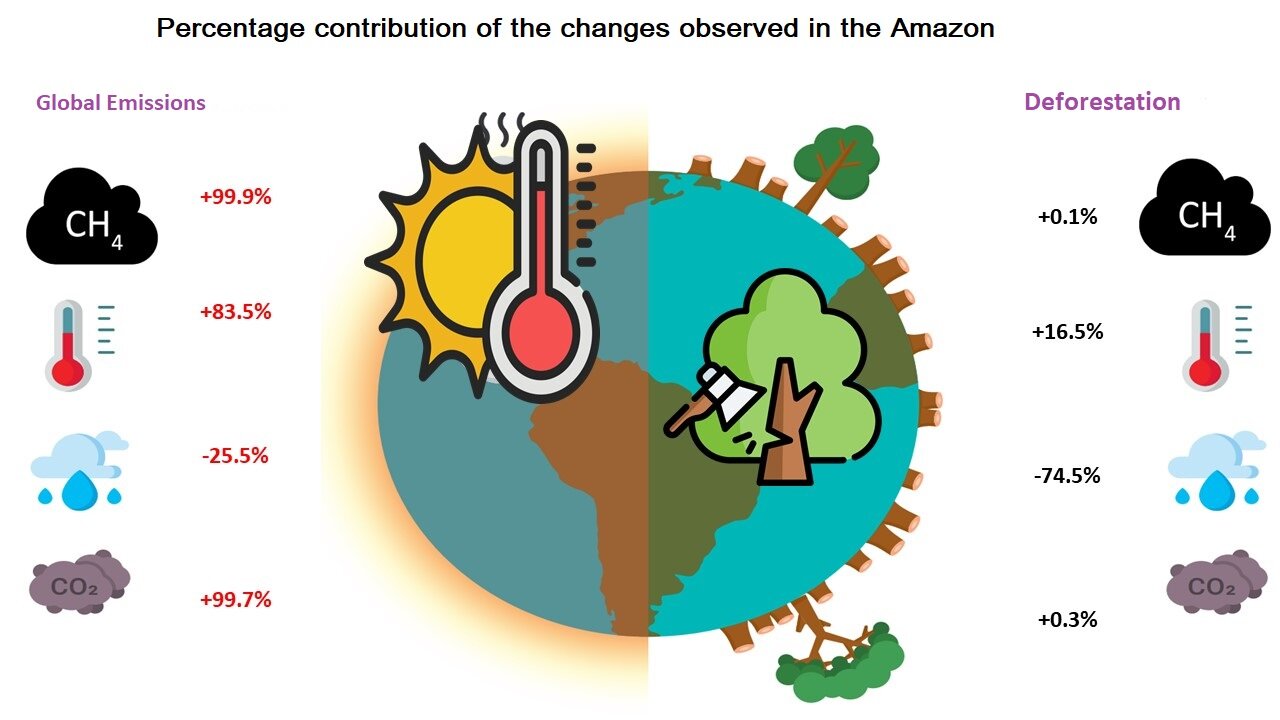

The research shows that deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon is responsible for 74.5% of the reduction in rainfall and 16.5% of the temperature increase during the dry season. Until now, scientists had known that rainfall was declining, that dry seasons were lengthening, and that temperatures were climbing. But they had not been able to separate how much of this was due to global greenhouse gas emissions—driven largely by industrialized nations in the Northern Hemisphere—and how much was caused by Brazil’s own land-use decisions.

By analyzing decades of data with advanced statistical models, the USP team has effectively drawn up what one of the authors calls an “account payable.” The results show that local deforestation is a key driver of the Amazon’s destabilization, intensifying the dry season and accelerating warming beyond the contribution of global climate change alone.

Rainfall during the dry season has dropped by 21 millimeters per year, with deforestation alone responsible for 15.8 millimeters of that decline. Meanwhile, maximum temperatures have risen by about 2 °C, with a measurable fraction tied directly to forest loss.

Why the First Cuts Hurt the Most

One of the most sobering findings is that the effects of deforestation are most severe in the early stages of forest loss. The most dramatic shifts in temperature and rainfall occur when between 10% and 40% of the forest disappears.

This means that even relatively small amounts of deforestation can trigger outsized disruptions to the ecosystem. The takeaway, according to Professor Marco Aurélio Franco of USP’s Institute of Astronomy, Geophysics, and Atmospheric Sciences, is unmistakable: the forest must remain standing. If it is used at all, it must be done sustainably, without conversion into pasture or large-scale monoculture.

The Fragile Balance of the Amazon

The Amazon is not just a collection of trees—it is a finely tuned atmospheric machine. Through a process often called the “flying rivers,” trees draw water from the soil, release it through their leaves, and send it skyward as vapor. These plumes form the seeds of clouds that later return as rainfall. Without this cycle, the Amazon cannot sustain itself—or the ecosystems and human communities that depend on it.

At the end of last year, another study co-authored by USP researchers revealed the physical-chemical mechanisms that drive rain formation in the Amazon. Aerosol nanoparticles, electrical discharges, and chemical reactions in the upper atmosphere combine to create a unique cloud-forming system. This “aerosol machine” is unlike anything else on Earth.

Yet deforestation interrupts this delicate cycle. Trees removed from the forest mean less moisture, fewer aerosols, and fewer clouds. The dry season lengthens. Forest fires spread more easily. And in a cruel feedback loop, the fires themselves release carbon dioxide and destroy even more vegetation, further weakening the rainfall machine.

The Scale of the Loss

The numbers paint a sobering picture. Between 1985 and 2023, the Brazilian Amazon lost 14% of its native vegetation, an area equivalent to the size of France. Most of this was cleared for pasture, replacing ancient ecosystems with cattle fields.

Even though deforestation rates have slowed in recent years, reaching their second-lowest level between August 2024 and July 2025 (4,495 km² cleared), forest degradation continues apace, particularly through fire. The dry season, running from June to November, now amplifies these effects, making each year hotter, drier, and more vulnerable to ecological collapse.

Global Versus Local Responsibility

The USP study also examined greenhouse gas levels over a 35-year span. Carbon dioxide rose by 87 parts per million, while methane increased by 167 parts per billion. Strikingly, more than 99% of these increases were linked to global emissions rather than local deforestation.

This finding highlights a difficult truth: while global industrial pollution drives rising atmospheric concentrations of greenhouse gases, local deforestation determines how those gases interact with the Amazon itself. Brazil’s choices do not control the global emissions trajectory, but they do control whether the Amazon remains a carbon sink or becomes a carbon source.

In short, the world is responsible for the scale of emissions—but Brazil is responsible for protecting the system that helps absorb them.

A Warning for the Future

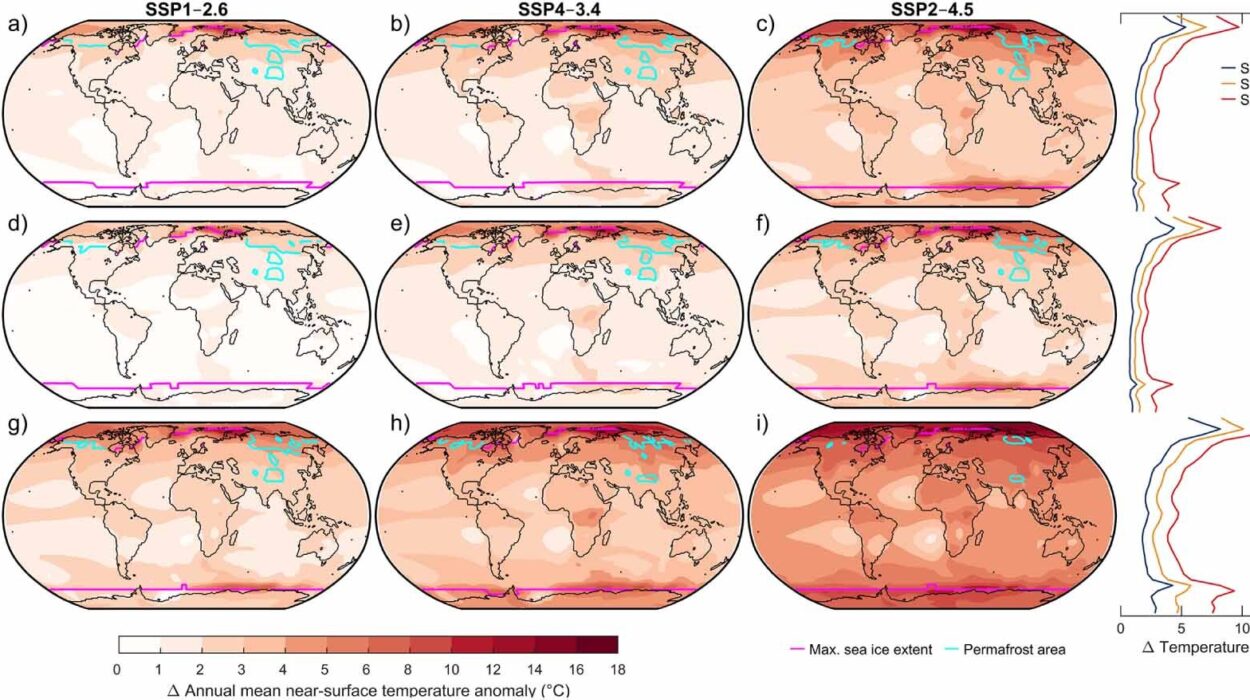

The researchers warn that unchecked deforestation will lead to even sharper declines in rainfall and more extreme heat. Recent droughts in 2023 and 2024 already demonstrate the risks. These events not only damaged ecosystems but also disrupted agriculture, hydroelectric power generation, and water supplies far beyond the forest itself.

Moreover, studies indicate that deforestation is reshaping the South American monsoon system. This seasonal rainfall, which sustains much of central and southeastern Brazil, is becoming weaker and less predictable. If the trend continues, vast regions could face chronic water scarcity, with devastating effects on food security and economic stability.

Beyond the Amazon: Why the World Should Care

The Amazon is not just a regional concern—it is a global one. Its forests store enormous amounts of carbon, regulate atmospheric circulation, and house one in ten known species on Earth. If it collapses, the consequences will reverberate across continents.

The loss of Amazon rainfall could destabilize food production in Brazil, Argentina, and beyond. Reduced carbon storage could accelerate global warming. Biodiversity loss would be irreversible, wiping out species that evolved over millions of years.

The Amazon’s fate is inseparable from humanity’s own.

Hope and Responsibility

While the study paints a troubling picture, it also offers clarity. By quantifying the impacts of deforestation versus global climate change, it gives policymakers a powerful tool. It shows that protecting the Amazon can make an immediate and measurable difference in maintaining rainfall and limiting heat.

As the world prepares for COP30 in Belém, deep in the Amazon itself, this research underscores the urgency of action. Protecting the Amazon is no longer just about conserving biodiversity—it is about climate stability, water security, and the survival of future generations.

The forest is not an obstacle to progress—it is the foundation of life. And every hectare preserved is an investment in a livable future.

More information: How climate change and deforestation interact in the transformation of the Amazon rainforest, Nature Communications (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-63156-0