When we think of deserts, we often picture death. Endless dunes of blistering sand, cracked clay plains, salt flats gleaming like glass beneath a punishing sun—landscapes so hostile, so stripped of moisture, they seem incompatible with life itself. Yet this perception could not be more wrong. Deserts are, in fact, alive with motion, sound, color, and complexity. Life in the desert is not absent—it is simply disguised, hidden behind ingenious adaptations and behavioral strategies that allow organisms to survive where water, the very elixir of life, is nearly nonexistent.

Across the Sahara, the Gobi, the Sonoran, and the Atacama, from burning sand to icy permafrost, a web of creatures thrives in ecosystems that, to the untrained eye, appear barren. The secret to their survival lies not in abundance, but in efficiency—a radical mastery of scarcity. Each animal, plant, and microorganism in the desert is a marvel of evolution, sculpted over millennia to endure the extremes. This is not just a story of hardship, but of triumph. It is the chronicle of how life refuses to yield, even in the driest corners of our planet.

Defining the Desert: Where Dryness is the Norm

Before exploring how desert wildlife copes with dehydration, it’s important to define what a desert is. Contrary to popular belief, a desert is not necessarily a hot place—it is a dry one. By meteorological standards, deserts are regions that receive less than 250 millimeters (10 inches) of precipitation annually. Some deserts, like the Antarctic Desert, are perpetually frozen, while others, like the Sahara, are infernos by day and freezing by night.

There are four main types of deserts: subtropical (like the Sahara and Arabian Desert), cold winter (such as the Gobi), coastal (like the Atacama), and polar (the Arctic and Antarctic). Each presents its own unique challenges to life, but they all share one common factor: water is scarce, and what little exists often arrives unpredictably, through rare rains, mists, or underground aquifers.

This scarcity demands extraordinary adaptations, not only to conserve water but to locate, extract, and utilize it with astonishing precision. In these regions, biology becomes a masterclass in resourcefulness.

Water is Life: The Central Challenge

Water performs essential functions for all living organisms. It is the medium in which cellular reactions occur, the transport system for nutrients and waste, and the coolant that maintains body temperature. Dehydration disrupts these processes and can lead to death in a matter of hours or days, depending on the organism. So how do desert animals, with little or no access to free-standing water, continue to function?

The answers are as varied as the creatures themselves. Some animals are nocturnal, avoiding the sun’s intensity altogether. Others have evolved highly efficient kidneys that concentrate urine to conserve fluids. Some absorb moisture from the food they eat, or from dew that condenses on their skin or burrows. Still others store water in fat reserves, utilizing metabolic processes to extract moisture internally.

But perhaps most fascinating of all are the animals that have developed behaviors and body structures so specialized, so attuned to desert life, that they seem almost alien in their design.

Masters of the Mirage: Behavioral Adaptations

In the absence of water, behavior becomes one of the most powerful tools in a desert animal’s survival toolkit. Timing is everything. Many desert animals are crepuscular—active only at dawn and dusk—or strictly nocturnal, emerging only when temperatures have dropped to manageable levels. The desert sun, with its fierce rays and dry heat, is an adversary not to be confronted directly.

Kangaroo rats, found in North American deserts, are quintessential examples. These small rodents rarely drink water in their entire lives. They spend daylight hours deep in their burrows, where humidity levels are higher and temperatures lower. Their burrow networks are engineered to trap moisture, and they seal them tightly to prevent evaporation.

Camels, icons of desert survival, are crepuscular browsers, feeding during the cooler parts of the day. They avoid excessive movement during the hottest hours and can raise their internal body temperature several degrees to prevent sweating, thereby conserving water.

Reptiles such as desert lizards and snakes will bask in the morning sun to raise their body temperature, then retreat into shade or burrows before the midday heat becomes lethal. Behavioral thermoregulation allows them to maintain optimal body function while minimizing water loss.

Even insects, like the Namib Desert beetle, display remarkable behavior. It climbs to the top of sand dunes in the early morning fog and raises its back to the sky. The beetle’s shell has hydrophilic bumps and hydrophobic troughs, which collect and funnel water droplets from fog directly to its mouthparts. Here, behavior and body morphology are inseparable, evolved in tandem to outwit dehydration.

Bodies Built for Drought: Physiological Marvels

Desert animals are not just behaviorally adapted to survive without water—they are physiologically transformed to do so. Evolution has sculpted organs, tissues, and cellular mechanisms that work tirelessly to retain every precious drop of moisture.

One of the most critical adaptations is in the renal system. Animals like the kangaroo rat and the fennec fox have highly specialized kidneys that can produce urine five times as concentrated as human urine. These kidneys extract the maximum amount of water from waste, allowing the body to function on minimal fluid loss.

Reabsorption of water also occurs in the intestines. Some desert reptiles and birds produce feces so dry they resemble pellets, conserving water through highly efficient digestion and resorption. The sandgrouse, a desert-dwelling bird, has feathers on its belly that can absorb and retain water. After finding a distant water source, the male sandgrouse soaks its plumage, then flies back to the nest, allowing chicks to drink directly from its feathers.

Evaporative cooling—sweating or panting—is costly in water. Desert animals often avoid it altogether. Camels, for instance, can lose up to 25% of their body weight through dehydration without suffering severe consequences, a capacity unmatched in most mammals. Their red blood cells are oval-shaped rather than round, allowing them to circulate more easily when blood thickens from dehydration.

Fat storage is another crucial adaptation. Camels do not store water in their humps, as the myth goes, but fat. This fat can be metabolized into energy and water—a process called “metabolic water production.” One gram of fat can yield about one gram of water when oxidized, a strategy that also benefits other desert dwellers like the thorny devil lizard and the oryx.

Cryptic Strategies: The Art of Staying Hidden

Camouflage is often considered a defense against predators, but in the desert, it also serves to protect against heat and water loss. Animals like the desert horned viper blend perfectly with the sandy substrate, not only to ambush prey but to remain hidden from the sun.

Burrowing is another common tactic. The Saharan silver ant, for instance, only emerges for about ten minutes each day when temperatures are high enough to deter predators but still survivable. Its reflective silver hairs deflect solar radiation, but it relies on underground retreats to regulate body temperature the rest of the time.

Many amphibians, such as the spadefoot toad, enter a state of estivation—a form of hibernation—during the dry season. They burrow deep into the soil and encase themselves in a cocoon of dead skin cells, reducing metabolic activity to nearly nothing. They can remain dormant for years, emerging only when rains return. This cryptobiotic strategy essentially allows the animal to pause life until conditions are favorable again.

Plants in a World Without Rain

Though the focus is often on animals, the true pioneers of desert survival are the plants. Without roots, leaves, and stems adapted to drought, no food web could exist. Desert plants employ two main strategies: drought tolerance and drought avoidance.

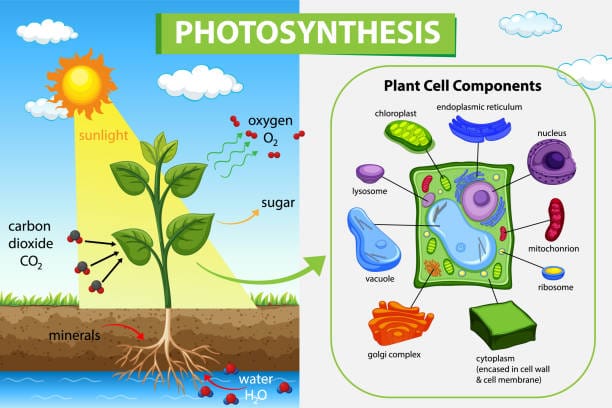

Succulents like cacti store water in fleshy tissues and are protected by waxy coatings and spines that reduce evaporation. Their shallow, widespread roots allow them to quickly absorb water from rare rains. Many use CAM (Crassulacean Acid Metabolism) photosynthesis, which allows them to open their stomata at night to reduce water loss during gas exchange.

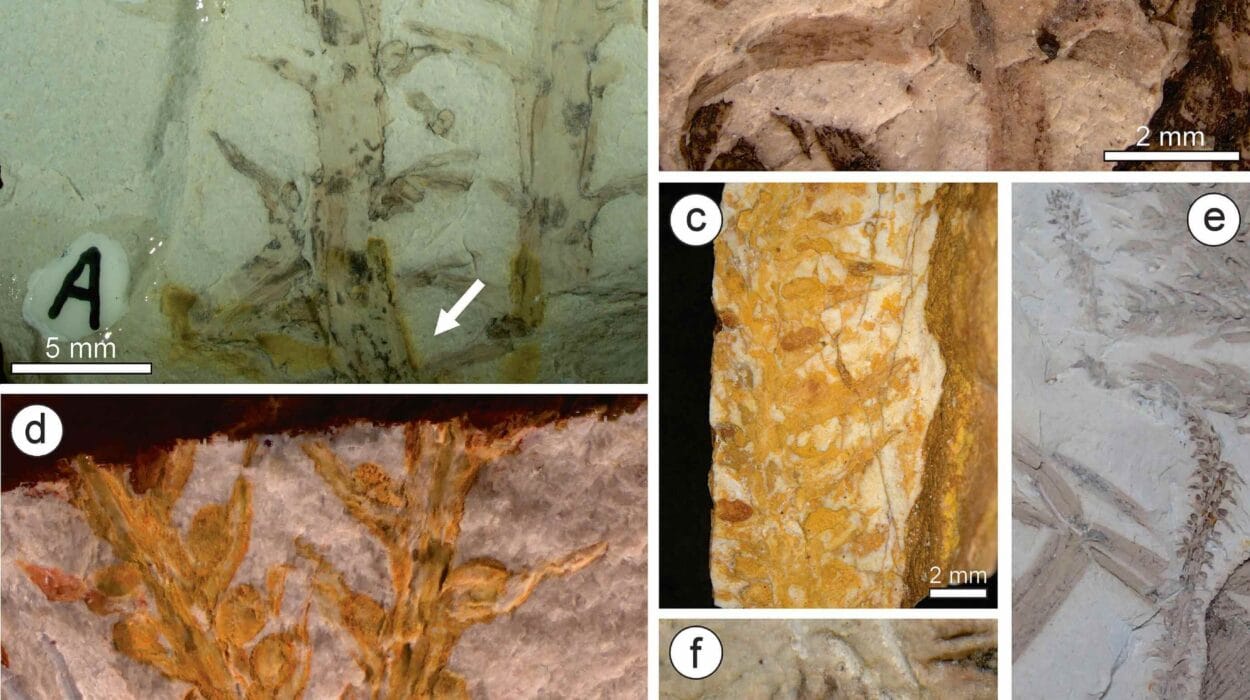

Other plants, like ephemeral wildflowers, avoid drought entirely. Their seeds remain dormant for years, germinating only when enough rain falls to support rapid growth, flowering, and reproduction—all within a few weeks. This strategy turns deserts into fields of blossoms almost overnight, a spectacle of survival wrapped in beauty.

Desert shrubs like creosote bush and sagebrush produce allelopathic chemicals that inhibit the growth of nearby plants, reducing competition for water. Their deep taproots can reach underground water reserves, while their small, wax-coated leaves minimize water loss.

These plants form the base of desert ecosystems, anchoring soils, feeding herbivores, and creating microhabitats. Without their ingenuity, animal life would have no foundation.

Microbial Marvels: Invisible Survivors

Even microorganisms have found ways to inhabit the driest places on Earth. In the Atacama Desert—often called the driest non-polar desert in the world—soil samples have revealed hardy microbes living in rock crevices, salt crusts, and gypsum deposits. These extremophiles derive moisture from hygroscopic minerals or thin films of fog, metabolizing in bursts when conditions briefly permit.

Cyanobacteria in desert crusts fix nitrogen and stabilize soils, preventing erosion and fostering conditions for higher plants. Others survive by forming endospores, durable structures that can remain dormant for decades.

The existence of such microbial communities has profound implications not only for desert ecology but for astrobiology, suggesting that life might persist on Mars or other planets under extreme conditions.

Death and Rebirth: The Role of Rain

Rain in the desert is rare, but when it comes, it changes everything. Seeds burst to life, insects swarm in mating frenzies, and reptiles emerge from hiding to feed and reproduce. Within hours, the desert is transformed from desolation to abundance.

Animals have evolved to anticipate and exploit these brief windows. The spadefoot toad can go from dormancy to mating within a single day of rainfall. Their tadpoles develop at an astonishing speed, reaching maturity in as little as two weeks before the temporary pools evaporate.

These cycles of sudden richness and long scarcity define the tempo of desert life. The organisms that thrive here are not merely survivors—they are opportunists, strategists, and masters of timing.

Deserts in Crisis: Climate Change and Human Impact

As robust as desert life may seem, it is not invulnerable. Climate change is altering rainfall patterns, increasing drought frequency, and pushing temperatures even higher. These shifts disrupt carefully balanced ecosystems, especially for species with narrow thermal or ecological tolerances.

Human activities—like overgrazing, mining, groundwater extraction, and urban expansion—further strain desert environments. Many species are now endangered, and invasive plants are replacing native vegetation, altering fire regimes and nutrient cycles.

Conservation efforts are often complicated by the false perception of deserts as empty or worthless land. But these ecosystems are reservoirs of biodiversity, cultural heritage, and scientific wonder. Protecting them is not only a moral obligation but an ecological necessity.

Lessons in Resilience

Desert wildlife offers profound lessons in survival, resilience, and adaptation. In a world increasingly shaped by climate extremes, the strategies employed by these organisms may hold keys to future innovations in agriculture, water management, and sustainability.

More than that, deserts challenge our assumptions about what life needs. They show us that thriving does not always require abundance—that elegance, efficiency, and timing can be just as powerful as raw resources. In their silence, deserts speak volumes.

Their creatures, whether slithering beneath the sand or blooming under moonlight, remind us that life is not deterred by hardship. It is defined by its ability to persist.

And so, beneath a merciless sun and against the backdrop of shimmering dunes, the desert remains alive—not in defiance of nature, but as its finest expression.