When Bob Taylor, co-founder of Taylor Guitars, acquired an ebony mill in Cameroon, his goal was practical: to secure a sustainable source of wood for the company’s world-renowned acoustic guitars. Ebony has been cherished for centuries for its dark, smooth, resonant qualities—used in piano keys, violin fingerboards, and guitar fretboards. But Taylor wasn’t content with just taking. He wanted to give back to the forest that provided his craft’s lifeblood.

Planting new ebony trees seemed like the obvious answer. Yet when he began asking questions—how do ebony trees grow? how many are left? how long do they live?—he discovered a startling truth: scientists didn’t know. Despite 200 years of craftsmen shaping ebony into instruments, basic knowledge of the tree’s biology was almost nonexistent.

That’s when Taylor crossed paths with Thomas Smith, a UCLA conservation ecologist and founder of the Congo Basin Institute. Smith had spent decades studying Africa’s rainforests and the delicate web of life that sustains them. When Taylor shared his vision, Smith saw an opportunity to merge two worlds: craftsmanship and conservation. Out of that meeting was born The Ebony Project, a nine-year partnership blending science, local communities, and an unlikely hero—the African forest elephant.

The Secret Life of Ebony Seeds

In 2023, Smith’s team published groundbreaking research in Science Advances, revealing the key to growing ebony trees: elephants.

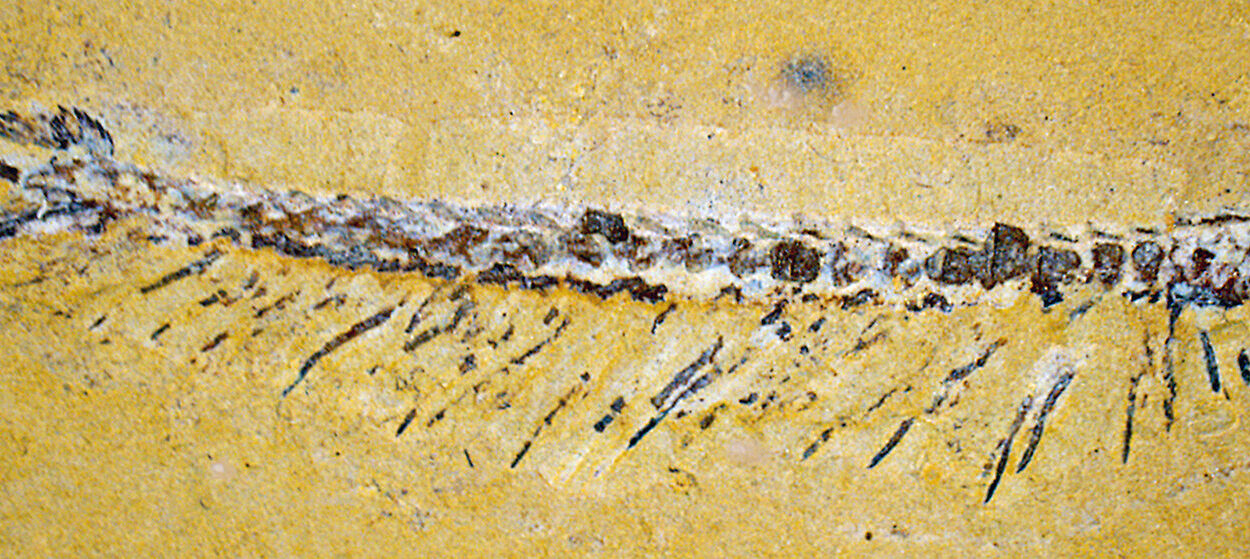

Ebony produces fruits with large seeds. For centuries, people assumed that planting those seeds in the ground would be enough. But the researchers found that something essential was missing. The trees had evolved alongside elephants, relying on them as seed dispersers.

Here’s how it works: elephants eat the ebony fruit, carry it in their massive digestive tracts, and deposit the seeds miles away. Wrapped in elephant dung, the seeds are not only fertilized but also stripped of the sugary pulp that would otherwise attract rodents. In other words, the elephant acts as both gardener and bodyguard. Without elephants, most ebony seedlings never survive.

In forests where elephants are hunted or have vanished, researchers discovered a shocking 68% decline in ebony saplings. Those that did exist were clustered right beneath the parent tree, making them vulnerable to inbreeding and disease. Genetic testing confirmed it: in elephant-free zones, ebony populations were shrinking, growing weaker, and becoming more vulnerable to the stresses of climate change.

Elephants: The Forest’s Architects

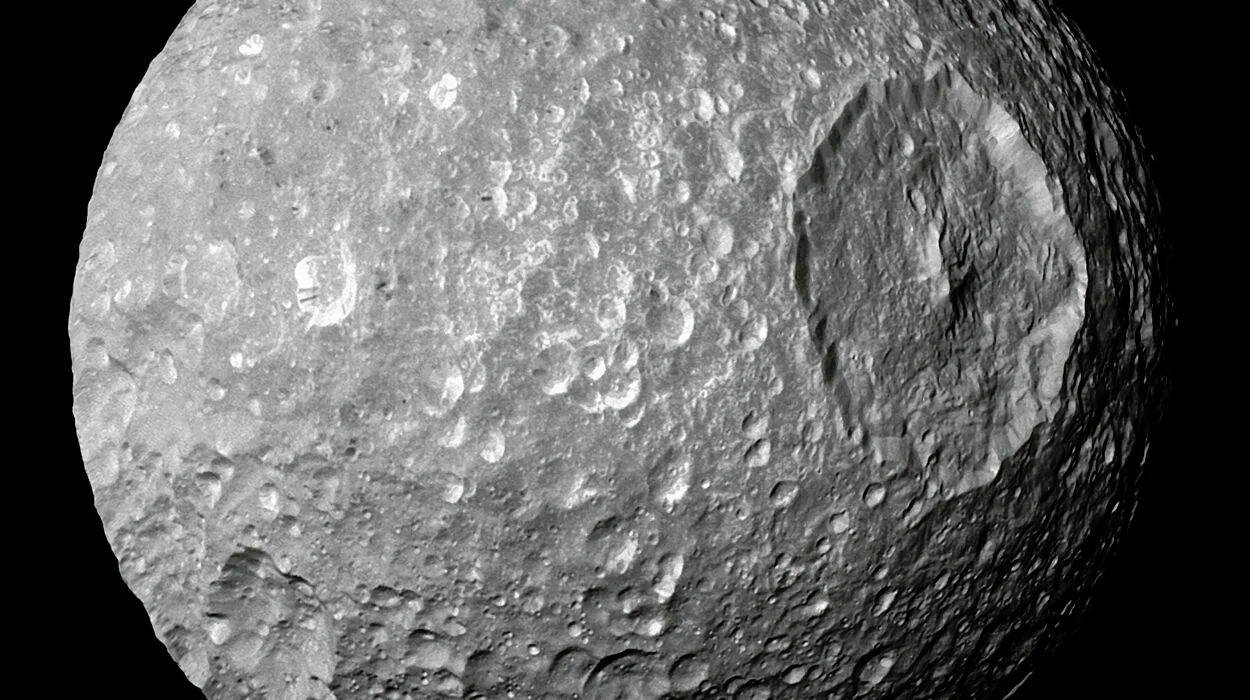

Forest elephants are more than just majestic animals—they are what ecologists call a keystone species, a linchpin holding entire ecosystems together.

“People think, ‘Oh, it’s a shame these magnificent creatures are threatened,’” said Smith. “But what they don’t understand is that we won’t just lose elephants—we’ll lose the ecological functions they provide.”

By dispersing seeds over vast distances, elephants ensure rainforests remain diverse and resilient. Without them, the forest begins to unravel. Trees grow too close to their parents, gene pools shrink, and regeneration slows. Eventually, entire forests risk collapse.

And the threat is real: in the past 30 years, forest elephant populations have plummeted by 86%, driven by poaching for ivory and habitat loss. In the Congo Basin today, elephants are absent from at least 65% of their historical range.

What’s at stake is not only a single species of tree but the future of one of Earth’s largest carbon sinks. Rainforests regulate climate, produce oxygen, and shelter countless forms of life. The fate of elephants and ebony is tied to our own.

Listening to the Forest Through Indigenous Knowledge

Science played a central role in uncovering the elephant-ebony connection—but so did Indigenous knowledge.

The Baka people, who have lived in the Congo rainforest for generations, had long observed something that outsiders had missed: ebony seedlings often sprouted in elephant dung. When researchers led by UCLA’s Vincent Deblauwe noticed stark differences between protected and hunted regions—saplings thriving in one, almost absent in the other—they turned to the Baka for insight.

Elder Gaston Guy Mempong explained the obvious to those who had not lived in the forest: “It’s because there are no more elephants in the hunting zones.”

This wisdom, passed down through generations of observation, confirmed what genetic testing and fieldwork later proved. The partnership with the Baka and Bantu communities became central to The Ebony Project’s success. Not only did they provide ecological knowledge, but they also helped map forests, collect seeds, and care for nurseries.

Planting Seeds for the Future

The Ebony Project has already planted over 40,000 ebony trees and 20,000 fruit trees, offering both ecological and economic benefits. The fruit trees provide food and income, while the ebony saplings represent a long-term investment—trees that may take a century to mature, but whose value will be inherited by future generations.

Importantly, all the trees belong to the local communities. By returning stewardship to the people who live in and depend on the forest, the project ensures sustainability. “My long view is that this project offers a grassroots approach to rainforest restoration,” Smith said.

For Bob Taylor, the experience has been transformative. “I’ve spent my life building guitars and growing a guitar company,” he reflected. “But being part of The Ebony Project has been one of the most fulfilling experiences of my life. It reminds me that sometimes the most important work is about planting seeds for others to benefit from.”

Music, Elephants, and the Web of Life

There is something poetic in the connection between music and elephants, ebony and ecosystems. The same wood that carries the vibration of strings, filling a concert hall with sound, also carries the story of a forest and the animals that sustain it. Every chord struck on an ebony fretboard is, in a sense, a note in a larger symphony—one that includes elephants, Indigenous knowledge, and human creativity.

The Ebony Project shows us that conservation is not only about saving trees or animals in isolation. It is about preserving relationships—between seeds and elephants, between forests and people, between craftsmanship and the natural world.

The Urgency of Now

The story of ebony and elephants carries an urgent message. The disappearance of megafauna is not a distant tragedy; it is happening now, and its consequences ripple across ecosystems. Just as the Amazon lost its giant ground sloths, leaving behind stranded tree species, Africa’s forests risk losing ebony and countless others if elephants vanish.

But this story also carries hope. It shows that unlikely partnerships—between a guitar maker, scientists, and Indigenous communities—can yield solutions. It proves that planting trees is not just symbolic but vital, and that by protecting elephants we protect forests, climate, and future generations.

As the researchers wrote, “If elephants are removed from the ecosystem, ebony populations will severely decline and may ultimately collapse.” But if elephants are protected, the forest can thrive.

Planting More Than Trees

In the end, The Ebony Project is not only about guitars, trees, or elephants. It is about the choices we make today for the world we will leave behind.

A guitar’s song may last a lifetime, but a tree’s life can span centuries. When Bob Taylor chose to plant ebony trees, knowing he might never see them mature, he embraced a truth we often forget: that the most meaningful legacies are not for ourselves, but for those who come after.

And in that sense, The Ebony Project is like music itself. Each note fades, but the song endures. Each tree grows slowly, but the forest remembers. Each elephant carries seeds, and with them, the future of the rainforest.

More information: Vincent Deblauwe et al, Declines of ebony and ivory are inextricably linked in an African rainforest, Science Advances (2025). DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.ady4392